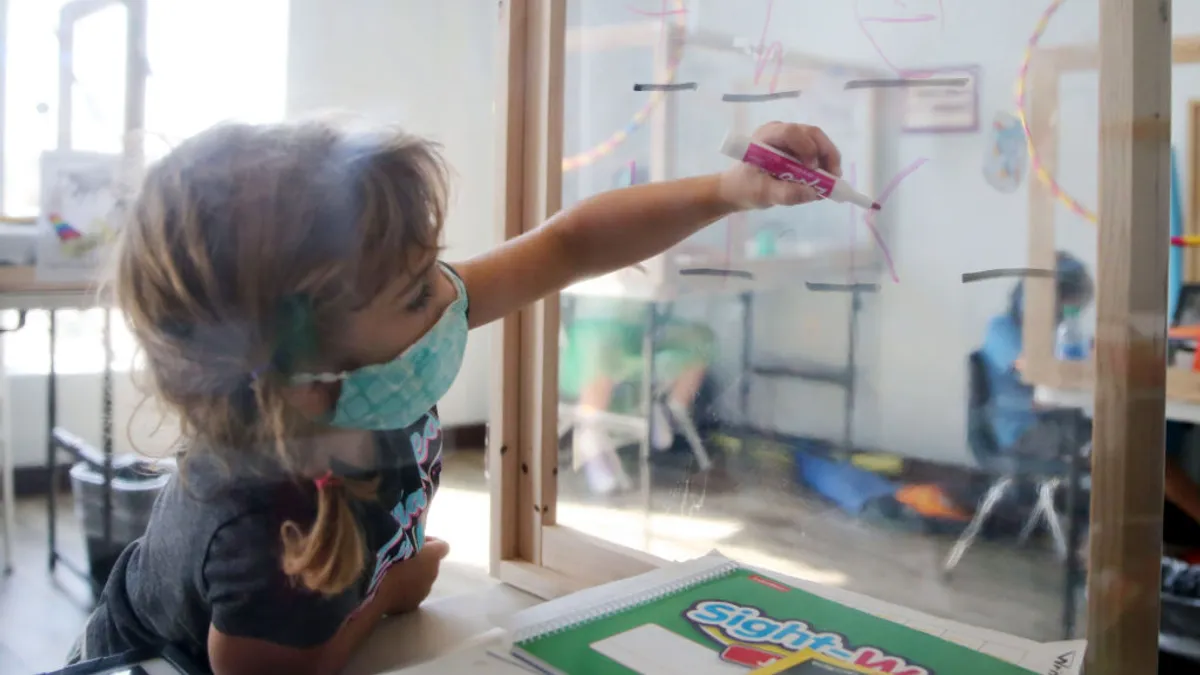

In the early months of the pandemic, when educators were quickly trying to figure out how to keep instruction going during stay-at-home orders, Doug Casey, executive director of the Connecticut Commission for Educational Technology, would get panicky phone calls from students’ family members trying to navigate online learning platforms and connect to the internet.

He also problem solved with leaders at the state education department, school districts, ed tech vendors and internet providers to get devices, internet and app access to students and educators. Through the chaos of meeting digital accessibility needs, Casey and state and local partners also focused on digital equity and making sure underrepresented students or students with unique circumstances such as having parents who live in different homes, could connect to remote learning.

While efforts to close the digital divide through device and internet availability are ongoing, attention is now being focused at the state, district, school and classroom levels to verify equity and effectiveness in student and teacher use of the available digital tools.

“Getting a computer into a student's hands is one thing, it just doesn't guarantee that they're learning anything,” said Casey, who is also chair-elect of the Board of Directors of the State Educational Technology Directors Association.

Collecting and analyzing metrics for educator and student ed tech engagement — even when learning is mostly in-person — is a critical step in knowing what products are being used, if they are effective, and if there are disparities to digital learning. That knowledge can help school systems better target funding and professional development toward digital learning tools that improve student outcomes for all students, ed tech experts said.

“It’s a huge challenge of just quantifying the problem,” Casey said.

Measuring engagement

Administrators, teachers and students are continually using ed tech tools for assessment, curriculum, operations and reference, but the pandemic’s forced move to virtual or hybrid learning increased the need for those products.

Before the pandemic, there was an average of 952 ed tech tools accessed each month by school districts, with at least 1,000 Chrome extension users. During the pandemic, that monthly average was 1,327, according to an analysis by LearnPlatform, a company based in Raleigh, North Carolina, that evaluates digital learning products for school systems. Google Docs was the most used ed tech product between July 1, 2019, and May 15, 2020.

In a survey of low-income families, respondents mentioned 51 different brands of online learning programs that were helpful for remote learning, according to a report published Thursday by New America.

LearnPlatform recently released a National EdTech Equity Dashboard showing K-12 web-based engagement across racial and economic student groups. The data was collected through LearnPlatform’s free Inventory Dashboard, which school systems can opt into to better understand how and when teachers, staff and students are accessing ed tech tools.

The National EdTech Equity Dashboard, for example, shows that in districts with more than 25% of students participating in free and reduced-priced lunch programs, digital engagement is consistently lower compared to districts with less than 25% participation. Racial gaps in usage are also visible. From January to May 2021, districts with more than 50% of students identifying as Black or Hispanic had lower levels of digital engagement, compared to districts with less than 50% Black or Hispanic student populations.

The information on the national dashboard, which is not disaggregated to the district level, is based on a sampling of student engagement of more than three million students with the more than 9,000 ed tech products currently in LearnPlatform's library. Individual school districts that have their own inventory dashboards and subscription-based tools can disaggregate usage data to the school and classroom levels, said LearnPlatform CEO Karl Rectanus.

The publicly accessible national equity dashboard should help districts see how their own metrics compare to national trends and could inspire research and conversations at the local level as to what could be done to address persistent gaps. Ed tech engagement information can also be used to inform policies, purchasing and processes, Rectanus said.

“One of the goals is to provide a level of context to inform, sort of, a shared fact base about what's actually happening across education technology and help the whole market be smarter about this,” he said.

Solving engagement barriers

After spending time and energy making sure all 41,000 students in Union County Public Schools in Monroe, North Carolina, had devices and internet access, attention is shifting to ensuring equity in usage, said Casey Rimmer, the district’s director of innovation and ed tech.

“We've set the baseline of who's got devices and who has access to the internet, but now the next question is really analyzing who's engaging with the content, how are they engaging, how often, and what type of engagements are happening,” Rimmer said.

The district’s usage trends are similar to the national gaps in equity. Using their local data, district leaders are able to hone in on some potential solutions, such as making online learning content available in the evenings for older students who are caring for younger siblings during the day, Rimmer said.

The usage data has also provided proof certain online tools adopted during the pandemic are worthy of longer-term investments because they were helpful for learning, such as digital science simulations to supplement in-person lab work, she said.

The data can also uncover products that aren’t contributing to student learning. Rimmer said that at the onset of the pandemic, the school district was “flooded” with free ed tech products, and teachers got dependent on certain products. With complementary use periods expiring, districts will need to weigh which products to continue supporting, she said.

“Schools have to get out in front of that and come up with a process to evaluate and determine what they're going to purchase, because a lot of teachers are going to demand a lot of things that they have been using for the last year on a free ticket,” Rimmer said.

Although state, district and school administrators may be able to use data analytic tools to monitor digital engagement and even identify trends that point to disparities, finding the root cause of why an individual student isn’t participating online would likely be the responsibility of the classroom teacher.

“Getting a computer into a student's hands is one thing, it just doesn't guarantee that they're learning anything.”

Doug Casey

executive director of the Connecticut Commission for Educational Technology

Teachers have the closest relationships with students and families and best understand why a student is not engaging in online learning. “Ultimately, to really sell families on the importance of being online, the importance of having their kids engaged for remote learning, you need to be talking to parents,” Casey said.

It’s also the combination of efforts at state and local levels to better identify students and teachers who lack home-based internet or devices, as well as school staffs and classroom teachers who can probe into why individual students aren't engaging, that will build all the evidence that could lead toward solutions, Casey said.

Community organizations, such as advocates for Spanish-speaking residents and faith-based groups, are also strong partners in determining how schools can help students overcome engagement barriers, he said.

“I think at a state level, it really, it points to the importance of having a really strong partnership with the local districts,” Casey said. “They know these families. They know there could be other issues going on at home.”

Dive Awards

Dive Awards