Lee Mason is a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA-D) and an associate professor of Special Education at The University of Texas at San Antonio, where he directs the Autism Research Center.

To receive special education services, students must meet the eligibility criteria for one of the 13 disability categories designated by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 2004. To access services, predefined criteria from one of these examples must adversely affect a student’s academic performance to a “disabling” degree. These disability labels do a disservice to students in a number of ways.

Teachers of children with autism frequently use the term “autism” to explain the behavior of their students. For instance, when a preferred toy is taken away from a young child with a language deficit, the teacher may explain the resulting tantrum as a function of his disability.

This circular reasoning detracts from the environmental factors that create skill deficiencies. Disability labels point to the behavioral deficits exhibited by the students who carry them, but they do not dictate a particular teaching methodology or instructional intervention.

The trouble with disability labels goes beyond fictional explanations for behavior. The use of disability labels may result in attributing the specific behavior of one individual classified with a particular category with all members of that group. For example, the movie "Rain Man" has left many people with the impression that all people with autism have advanced mathematical abilities. This limited frame of reference for understanding a complex disorder often leads to the overgeneralization of individual attributes.

Pairing strong mathematical abilities with autism spectrum disorder may lead someone to stipulate that other people with autism are also good at math. While such an accusation is not so inflammatory in and of itself, more often than not, this way of thinking disadvantages students stigmatized by disability labels.

Suppose you find out that you have a new student coming into your classroom. What do you know about this student? Almost nothing, other than perhaps a name, gender and age.

Now suppose you find out that the student has autism. What do you know about this student now? Perhaps he has a fondness for anime, which you can use as a reinforcer for shaping social interactions. Perhaps he flaps his hands and engages in vocal stereotypes that alienate him from his neurotypical classmates. Then again, perhaps not.

Rather than attributing cause to the disability, we believe that the practice of using labels to explain behavior is simply a category error. Many students who exhibit language delays, social skills deficits and circumscribed behavior do not also have autism, and their struggles are certainly not caused by autism. Instead, the skill deficits exhibited by these students are members of the class “Autism Spectrum Disorder.” That is, the label "ASD" describes a constellation of behavior exhibited by students who struggle with human interactions.

Moreover, this list is not comprehensive, and will perhaps never be exhaustive. As language and social skills difficulties are examined across novel contexts, we may choose to place them within this category or another. Our frame of reference for understanding disabilities is always limited by our background experience. In this way, no two perceptions of a disability are exactly alike — just as no two people, with or without autism, are exactly alike.

Over the past 20 years, the term “neurodiversity” has grown from a reference to the autism community to a description of individuals with a broad range of emotional, behavioral, learning, developmental and intellectual disabilities. This perspective may be further extended to all aspects of cultural diversity.

Who we are is a result of what we do. The individual differences between us stem from our unique histories and personal experiences over the course of a lifetime. Having a disability has less to do with a physical impairment than is does with how an individual has been treated because of this physical impairment. People are different to the extent we make them dissimilar from us. As members of each other’s environments, we have the power to exacerbate or mitigate these differences.

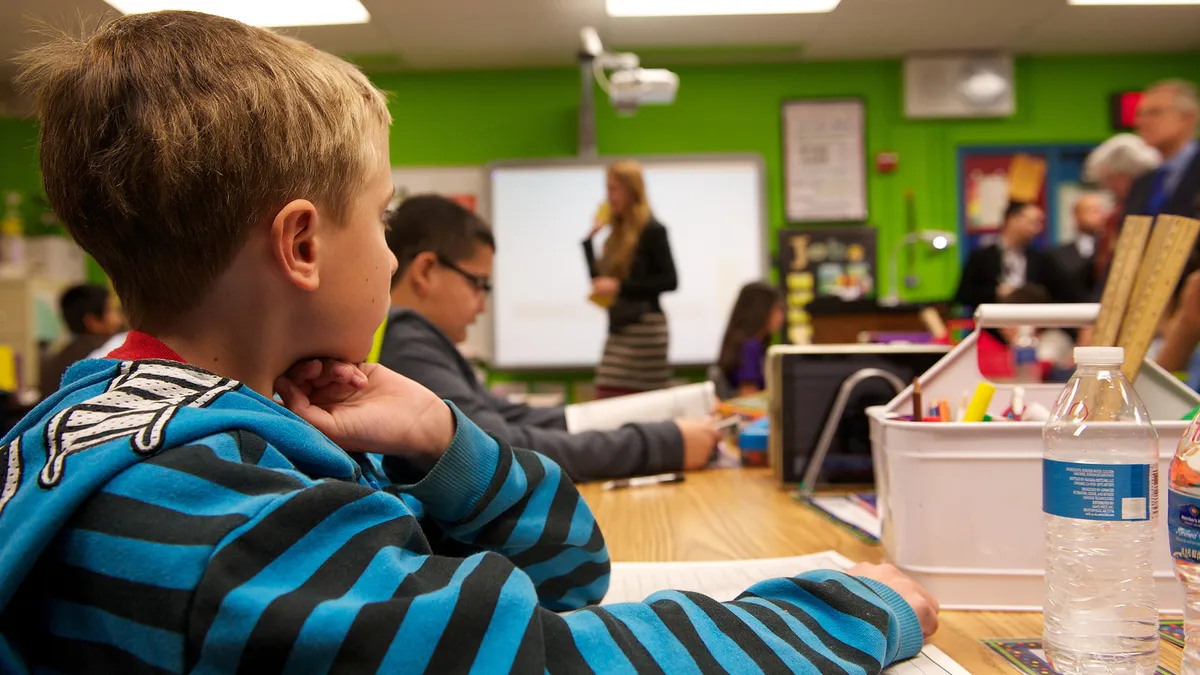

Terms like “disability” refer more to an individual’s environment than an inherent characteristic of the person. Rather than singling out the special education student, the onus of learning is placed upon the teacher, who constructs the classroom environment and manages contingencies.

In a neurodiverse society, education is not an attempt to "cure," "fix," "repair," "remediate" or even "ameliorate" a child's "disability." Through a functional contextual lens, neurodiversity promotes a deep, abiding respect for each child's unique differences, resulting in an individualized education in which the environment, not the child, is corrected.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards