When talking about how the Holocaust fits into curricula, Andrea Szőnyi will sometimes hear questions as to why conversations about other genocides aren’t included.

Szőnyi, the acting deputy director of programs for the University of Southern California Shoah Foundation, said this point of view reflects a “competition of suffering” and is a misguided response to the educational mission she and other Holocaust experts have set.

“The bulk of our archives is around the Holocaust, but we also have other materials on the Rwandan, Armenian and Cambodian genocides, the Bosnian conflict and others,” said Szőnyi. “When you go into the individual stories, you will see suffering is suffering, and pain is pain. There should be no competition.”

In some cases, teachers have also been told to construct a Holocaust curriculum that looks at “opposing” sides of the issue or to limit class discussions on “divisive” topics altogether. In 2021, an administrator in Texas’ Carroll Independent School District reportedly told teachers if they had a book about the Holocaust in their classrooms, they must also provide a book presenting an “opposing” viewpoint. And last year in Ohio, Democrats suggested a classroom censorship bill proposed in the Ohio Statehouse would require teaching “both sides” of the Holocaust.

Teaching students about the Holocaust in this environment can be daunting. But experts say there are approaches curriculum designers and educators can use to keep lessons grounded in history and improve teachers' confidence in the material they’re presenting.

There are not two sides

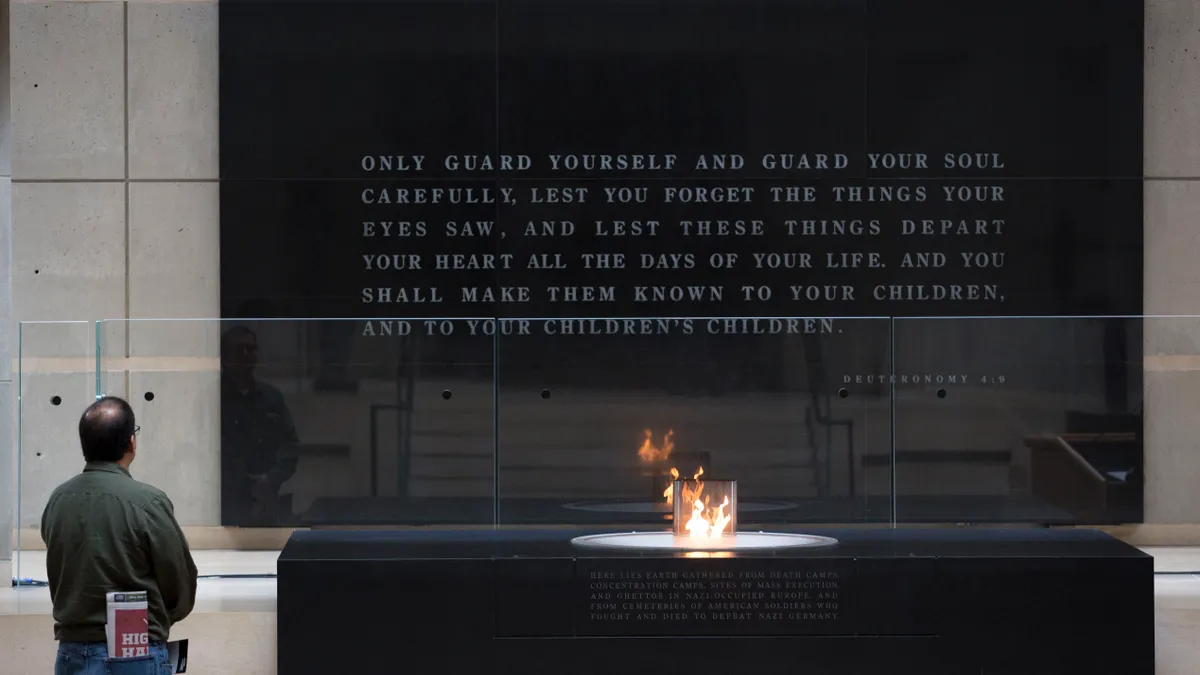

Gretchen Skidmore wants to make one point clear to all educators: They cannot teach opposing sides of the Holocaust because two sides do not exist.

“The Holocaust is the most documented case of genocide in history,” said Skidmore, director of education initiatives for the William Levine Family Institute for Holocaust Education, part of the U. S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. “There are not two sides.”

Those who try and argue there are two sides to the Holocaust imply there is something untrue in the evidence collected over decades from survivors, said Sheryl Ochayon, the Jerusalem-based project director for the Echoes and Reflections program at Yad Vashem’s International School for Holocaust Studies. To claim these stories have another side is to claim all of those testimonies were false.

Educators can find many of these testimonies online through the USC Shoah Foundation, Yad Vashem and other institutions — and available to pull up on a computer or mobile device to share and play for classes.

“When you say there are two sides to the Holocaust, it is tantamount to denying,” said Ochayon.

Find trusted resources

Skidmore said 24 states have laws requiring lessons about the Holocaust. Other states without legislative mandates include curriculum about the Holocaust in their standards. But educators in any state can develop a curriculum by turning to partners and resources, including pre-designed lesson plans for K-12 classes

One starting point for a discussion is to look at the symbols used during the Holocaust. Educators can talk with students about the meaning of these symbols, how they were employed and their connection to antisemitism, said Skidmore.

Yad Vashem, for example, has printed materials about the badges Jews were forced to wear during the Holocaust and the period leading up to it. The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum has a specific lesson plan, among its dozens for middle and high school students, on teaching students about Nazi symbols. The roughly one-hour program focuses on use of these symbols as well as where they came from in history.

Skidmore encourages educators to look for local institutions for support and materials, pointing to the Association of Holocaust Organizations, an international membership alliance, as a source. In addition, the Holocaust Museum is hosting a virtual conference in June where educators can access materials, hear directly from survivors, and connect with other teachers.

“We have a community that plays a role in states we could never play,” Skidmore said. “It’s also nice to join a network online of educators who interact with us.”

Connect the past to the future

To Szőnyi, another way to approach teaching about the Holocaust is to focus on how to link the past to the future.

“We teach about the past for the future, and we do that intentionally to make it relevant to students,” said Szőnyi, who also serves as the director of the Zachor Holocaust Remembrance Foundation, an educational organization based in Budapest, Hungary. “We have a page to reflect on their own stories and dilemmas. It is important they can relate.”

By connecting to the personal stories of survivors, students are more likely to develop empathy for them, said Ochayon. Educators could then link these stories of the past to experiences of today and discuss the Holocaust within the context of contemporary antisemitism.

Lessons can also be broadened to include media literacy, which Ochayon called a crucial skill to understanding the climate in Germany that gave rise to the Holocaust.

The march to Hitler’s “Final Solution” was fueled by media illiteracy, “and today we see the same thing with fake news and spin,” Ochayon said. "Media literacy is important in terms of responding to antisemitism.”

However educators choose to approach the Holocaust with students, whether as a media literacy lesson or one that links the antisemitism of the past to that of today, steeping themselves in the facts and resources will bolster their confidence if faced with pushback on lesson plans.

Ochayon said she understands schools often employ a two-sided approach, such as when students are asked to each tell their experience about a disagreement or fight while standing in a principal’s office. But she emphasized the Holocaust is not an issue, it is a fact.

“An issue is one thing, and historical fact is not something you can argue with,” Ochayon said. “It is proven and documented, and there is no other way to present it. The Holocaust is a historical fact.”

Dive Awards

Dive Awards