Sandy Donahoe's daughter, Kellyn Donahoe, is taking classes, living in a dorm and attending social events at Kent State University in Ohio. This is the type of college experience Donahoe always envisioned for her 20-year-old daughter, and Kellyn, who has Down syndrome, worked hard — even as a young child — to reach her highest potential in school.

But the journey had its ups and downs. Donahoe initially battled the local Ohio school system to enroll Kellyn in a general education kindergarten classroom rather than a more restrictive placement for students with disabilities.

Kellyn was indeed included in class with her nondisabled peers starting in kindergarten. But, Donahoe recalls, "the early years were tough" as she pushed teachers and administrators to let Kellyn learn from the general education curriculum alongside her peers who were not disabled.

But year after year, Kellyn met benchmarks and was driven to do well, because teachers, support staff and her family provided accommodations and supports, Donahoe said.

"Teachers learned how to work with a variety of different students, and when you have someone who's highly motivated, it's much easier," Donahoe said. Conversations between school staff and Kellyn's parents became less about if Kellyn could be included and more about how she would be included, Donahoe said.

Kellyn graduated with a regular diploma from Ohio's Lakewood City Schools near Cleveland in 2022. The next year, she keynoted the district's staff convocation, speaking about how her inclusion in school shaped her path to college.

"We weren't going to put her in an environment that we thought wouldn't work for her. We weren't trying to prove a point. We were trying to give her a full life."

Sandy Donahoe

Mother of Kellyn Donahoe

Kellyn was born in 2004 — the year of the last major update to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, the federal law that requires schools to provide a "free, appropriate public education" to students with disabilities. The law, passed with bipartisan support, also helps states furnish early intervention services to infants and toddlers with disabilities and developmental delays.

President George W. Bush signed the reauthorization on Dec. 3, 2004 at a ceremony attended by politicians, children and others.

Now, 20 years later, special education experts, advocates and families say the law — which addresses specialized services for infants through young adults — was well written. And there has seemingly not been political appetite to push Congress to open the law for another reauthorization.

"There is an entire generation of leaders and teachers who have never experienced any other version of IDEA other than this one," said Kevin Rubenstein, president of the Council of Administrators of Special Education.

Still, challenges remain.

Many experts say implementing the law in each classroom and district — as intended — has been one of the biggest difficulties. The pain points, however, have more to do with underfunding for IDEA and lack of qualified personnel than the words and intent of the statue, some say.

What changed with the 2004 law

When Congress reauthorized IDEA in 2004, it became the latest iteration of the law created in 1975 as the Education for All Handicapped Children Act. But the 1997 and 2004 updates that made schools accountable for the academic performance of students with disabilities stand as the most significant in the statute's history, some special education experts say.

"When you think about where we've come from, even in the last 20 years, the idea that we're going to assess students [with disabilities], that they should have a right to really quality curriculum materials, that they're going to be included in general education classes to the greatest extent possible — those are some big things and novel concepts that have come along as a result of this," said Rubenstein, who began his teaching career just as the 2004 reauthorization became law.

During that same time, Stephanie Smith Lee headed the U.S. Department of Education's Office of Special Education Programs. Just three years earlier, in 2001, Congress had reauthorized the Elementary and Secondary Education Act as the No Child Left Behind Act, which then transformed into the Every Student Succeeds Act with a 2015 bipartisan update. No Child Left Behind helped shape IDEA 2004's inclusion of students with disabilities in school accountability systems, Lee said.

"That alignment of IDEA and what's now called ESSA was critically important for both instruction for students with disabilities and accountability for the academic achievement of students with disabilities," said Lee, who is now policy and advocacy co-director at the National Down Syndrome Congress. Lee's daughter, Laura Lee, an advocate, a graduate of George Mason University, and a World Bank employee who was born with Down syndrome, died in 2016.

The 2004 law's emphasis on universal design for learning opened the door for schools to adopt different instructional strategies and personalized ways students with disabilities could demonstrate their knowledge. Those approaches aimed to make accessing the general curriculum easier for students with disabilities.

The statute also spawned development of two additional approaches for helping students with and without disabilities based on the intensity of their needs: multitiered systems of support and response to intervention.

Those two approaches were crucial for students who were suspected of having a specific learning disability, said Jacqueline Rodriguez, CEO of the National Center for Learning Disabilities, in an email.

Prior to the 2004 update, schools relied on comparing a student's IQ assessment with their academic progress. If the gap between the two was wide enough, then the student might qualify for IDEA services. Rodriguez said that requirement forced schools and families to wait for a student to "fall significantly behind."

Of the 7.5 million students ages 3-21 who qualified for special education services in the 2022-23 school year, 32% had a specific learning disability, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. That was the most common disability category, followed by speech or language impairment at 19%.

The 2004 law allowed for early intervention services and supports for students with learning challenges, Rodriguez said.

Both universal design for learning and multitiered systems of support have now become go-to general and special education practices.

Lee said the 2004 law also put a greater emphasis on postsecondary outcomes by requiring schools to summarize academic and functional performance for every student with disabilities leaving high school.

"The emphasis on both academics and functional skills and abilities helps now with students transitioning to employment, postsecondary education, and the rest of their life," Lee said. "That's been a real improvement."

Think College, a national technical assistance and research center, hosts a database of about 350 postsecondary education programs for students with intellectual disabilities offering degree, credential or nondegree programs. That's up from about 250 college programs serving these students in 2010, and half of those programs were considered dual enrollment programs, according to a paper published that year by the Postsecondary Education Research Center.

Donahoe says Kellyn made the transition from high school to college because of her will to succeed, and also because she and Kellyn's father, Chris, advocated for their daughter and partnered with teachers through the years. It also helped that they were familiar with the school system. Donahoe is a former teacher there, and Chris has been director of operations for the past 10 years.

"I never gave up," Donahoe said of advocating for Kellyn's inclusion in general education and in extracurricular activities.

In some cases, Donahoe didn't ask the school system for permission to include Kellyn in activities. "We would say, 'Oh, she's going to come to cross country practice,'" Donahoe said, adding, "We weren't going to put her in an environment that we thought wouldn't work for her. We weren't trying to prove a point. We were trying to give her a full life."

What's missing in the law

Despite all the progress that helped Kellyn and others succeed in general education environments, struggles remain with the national special education mandate.

Funding, for one thing, has never reached the promised levels.

When Congress approved IDEA 2004, the bill included a 10-year path to "full funding," which pledged that the federal government would contribute 40% of the additional per-pupil cost for special education services. However, that funding target — originally set by Congress upon creating the law in 1975 — has never been met, or even come close. The federal contribution for fiscal year 2025 is estimated at about 10%, or around $1,810 per student.

"It's an unfunded mandate, per se," said Laurie VanderPloeg, OSEP director from 2018 to 2021 and currently associate executive director for professional affairs at the Council for Exceptional Children.

"And particularly when we're looking at the educator shortage issue and training and resources, we feel that the field is doing the best they can within the resources that they have available to them," said VanderPloeg, "but it certainly does create challenges" for states and local school districts to ensure that a free appropriate public education is really being provided.

A multiyear, $6.6 million study, funded by the Education Department, is underway to examine the costs of educating students with disabilities. The last comprehensive federal research into this topic was conducted more than 20 years ago.

Another barrier has been shortages of both special educators and specialized support staff . For the 2023-24 school year, 77% of public schools reported it being "somewhat" or "very difficult" to fill special educator roles, according to an NCES survey.

"There is an entire generation of leaders and teachers who have never experienced any other version of IDEA other than this one."

Kevin Rubenstein

President of the Council of Administrators of Special Education

Some districts and states are taking innovative recruitment and retention measures, such as creating grow-your-own and apprenticeship programs for on-the-job training. Still, the shortages have forced districts in some cases to hire underqualified staff who may not be trained in developing IEPs and specialized instruction.

Likewise, high turnover in special education teachers and administrators may be contributing to disappointing results in annual federal accountability measurements. About 38 states, territories and the District of Columbia received a “needs assistance” label for implementing special education requirements and improving student outcomes — either for the year evaluated or for two or more consecutive years, according to a list of state determinations issued by the Education Department earlier this year.

In another closely watched metric, special education students nationally are disproportionately disciplined and are restrained and secluded at higher levels than for the overall student population. And there are racial disparities in the identification, placement and discipline of students with disabilities.

Denise Marshall, CEO of the Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates, a nonprofit that supports the educational rights of children with disabilities, says those disparity trends are frustrating. The problem isn't with how the law and regulation are worded, Marshall said, but rather a "lack of will and adherence to the law."

Federal special education law over the past 5 decades

-

Nov. 29, 1975President Gerald Ford signed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (Public Law 94-142), or EHA, into law. The law guaranteed a free appropriate public education, or FAPE, and an individualized education program for each child with a disability in every state and locality across the country. Before PL 94-142, there was no federal requirement for educating students with disabilities.

-

Oct. 8, 1986The main provision in these amendments to EHA (Public Law 99-457) addressed early intervention and created a state grants program to provide early intervention services for infants and toddlers with disabilities and their families. This section of the law is now known as Part C. Previously, these services were not available until a child reached 3 years old.

-

Oct. 30, 1990This EHA reauthorization changed the law’s name to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, or IDEA (Public Law 101-476). Two new disability categories were added: autism and traumatic brain injury. Additionally, Congress mandated that an individual transition plan must be developed — as part of the student's individualized education program — to help the student move on to postsecondary life.

-

June 4, 1997Access to the general curriculum for students with disabilities was a major focus of this IDEA reauthorization (Public Law 105-17). The law also allowed states to expand the definition of “developmental delay” to include students up to age 9. Additionally, the law gave parents an opportunity to try to resolve disputes with schools and local educational agencies through mediation and provided a process for doing so.

-

Dec. 3, 2004This reauthorization (Public Law 108-446) called for early intervention services for children not currently qualified for IDEA services but who need additional academic and behavioral support to succeed in a general education environment. It also required greater accountability for improved educational outcomes for students with disabilities and raised standards for instructors who teach special education classes.

What's next

Some special education professionals and advocates are reluctant to publicly predict the areas that would be prioritized for change if and when Congress takes up another reauthorization. Several, in fact, said they hoped that wouldn't occur anytime soon anyway.

IDEA "does what it's intended to do in relation to protecting the rights of students with disabilities who are the most vulnerable to having their rights being abridged through segregation, through discrimination on the basis of their disability," Marshall said. "We do not want to open up the law and risk losing the protections that are so important."

Rubenstein, the CASE president, said as he understands it, an IDEA reauthorization would be "a really a big deal. All of the regulations change, and all of the pieces there are up for discussion, and so it may impact the field more than prior reauthorizations have."

Many special education advocates and school administration organizations say they would oppose attempts to amend IDEA in phases, because changes should be considered holistically.

"Give the law a chance. Put the money behind the mandate so that we can execute in the way that it was designed to be executed."

Kuna Tavalin

Senior advisor for policy and advocacy for the Council for Exceptional Children

Some proposals laid out by the incoming Trump administration, however, have many in the special education field on the defense.

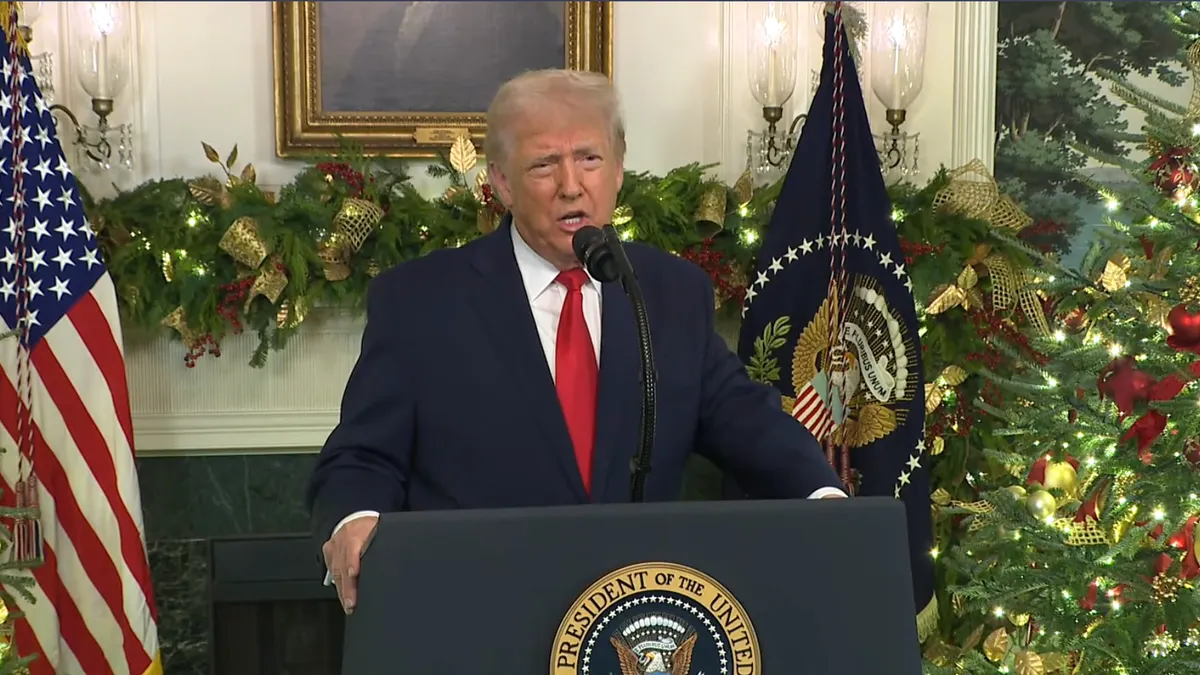

President-elect Donald Trump has suggested closing the Education Department altogether.

Additionally, the controversial Project 2025 — a policy document drafted by the conservative Heritage Foundation during the campaign for a hoped-for Trump administration — recommends sending IDEA funding directly to districts. This funding would be provided through "no-strings" formula block grants targeted at students with disabilities and distributed directly to local education agencies by the U.S. Health and Human Service Department's Administration for Community Living, the document says.

Another Project 2025 recommendation encourages state expansion of education savings accounts or private school vouchers for students with disabilities. Those moves could help ease the special educator shortages in public schools, say proponents.

Rodriguez, with the National Center for Learning Disabilities, said the organization plans to oppose attempts to block-grant IDEA or transform funding into a private school voucher program. "These proposals would fundamentally turn back the clock on progress for students with disabilities," she said.

Kuna Tavalin, senior advisor for policy and advocacy for the Council for Exceptional Children, said the organization's message to Congress has been: "Give the law a chance. Put the money behind the mandate so that we can execute in the way that it was designed to be executed."

Dive Awards

Dive Awards