Dive Brief:

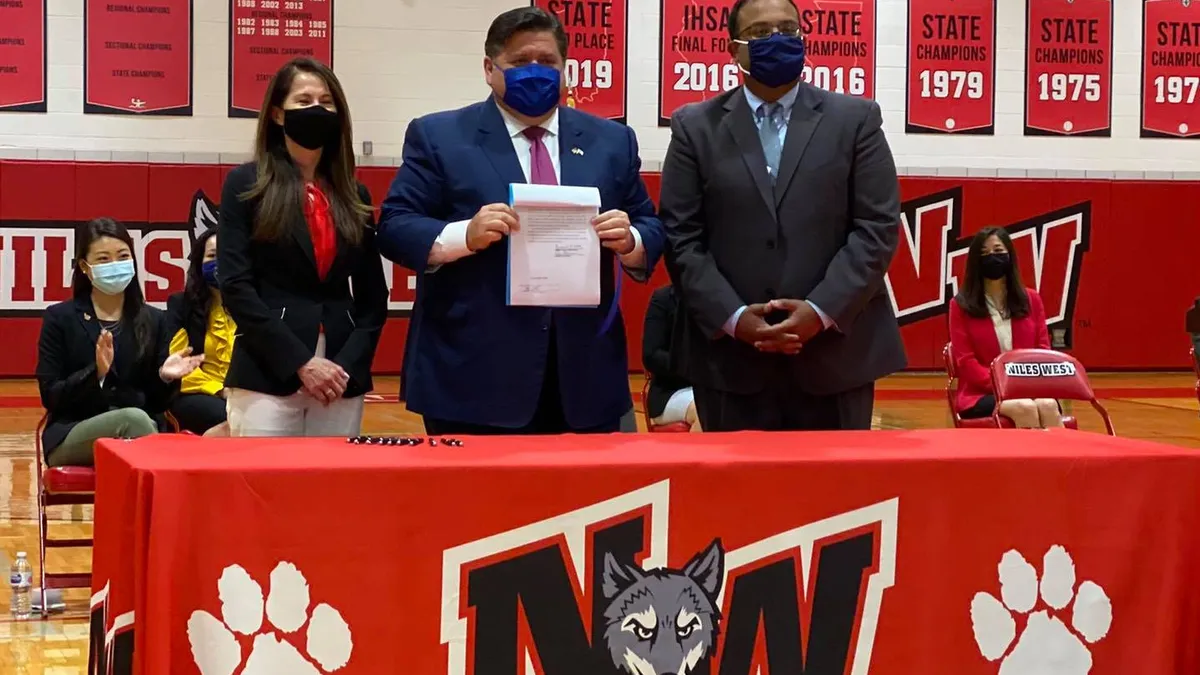

- Illinois became the first state requiring public schools to teach Asian American history after Gov. JB Pritzker signed into law HB 376, the Teaching Equitable Asian American History Act.

- Beginning in the 2022-23 school year, Illinois elementary and high school students will learn at least one unit covering Asian American history, including Asian Americans' contributions to society, as well as Japanese internment camps during World War II permitted by former President Franklin Roosevelt, legal challenges to the executive order establishing the camps, and reparations issued under President Ronald Reagan in 1988.

- While the state superintendent may provide guidance and instructional materials for use in developing a unit of instruction under the law, local boards will have the flexibility to tailor their instructional materials and determine what qualifies as a unit of instruction to meet the law's requirements.

Dive Insight:

In a statement, Pritzker said the requirement would create "more inclusive school environments" and help "truly reckon with our history" as a nation.

"Empathy comes from understanding," State Rep. Jennifer Gong-Gershowitz, a Democrat, said in a statement. "A lack of knowledge is the root cause of discrimination and the best weapon against ignorance is education."

The signed legislation, which passed both chambers of Illinois' legislature with bipartisan support, is part of a broader push for cultural competency in the classroom and is more specifically intended to address racism against Asian Americans. "The studying of this material shall constitute an affirmation by students of their commitment to respect the dignity of all races and peoples and to forever eschew every form of discrimination in their lives and careers," the law says.

In the months following early school closures sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic, a national survey by America's Promise Alliance of 3,300 high schoolers ages 13-19 found Asian students were more likely than their peers of other races to feel disconnected from their school environments. They were also more likely to respond that their “emotional and cognitive health” worsened during the pandemic.

“These findings suggest that young people are experiencing collective trauma,” said Dennis Vega, the interim president and CEO of America’s Promise Alliance at the time, in a statement. Over a year later, some Asian Americans, including students, are still reeling from spikes in anti-Asian racism in the wake of the pandemic.

Even prior to the pandemic, data showed Pacific Islanders, when viewed separately from broader Asian American groupings, were more likely to be disciplined in school compared to their white peers.

Trends showing the different treatment of Black, Hispanic and some Asian students have only added to the push for culturally competent instructional materials, especially in history and social studies. However, Republican efforts to ban or limit the teaching of systemic racism, as only one part of those materials, have spread in states including Tennessee, Idaho, West Virginia, Iowa, Missouri, New Hampshire, Oklahoma and Rhode Island.

On the other hand, states like Illinois have proactively passed legislation requiring instruction around diversity and inclusion or, more specifically in some places, on the history of racism in the United States. However, debates around "ethnic studies" have sometimes even stalled due to political pushback, as was the case in California, which in March passed a framework for teaching about Native Americans, African Americans, Latin Americans and Asian Americans in the state.

According to the Education Commission of the States, similar legislation calling for Asian Pacific American or Asian American instruction was introduced in 2021 and is pending in Iowa, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York and Texas. A measure in Connecticut was not passed.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards