Lessons In Leadership is an ongoing series in which K-12 principals and superintendents share their best practices and challenges overcome. For more installments, click here.

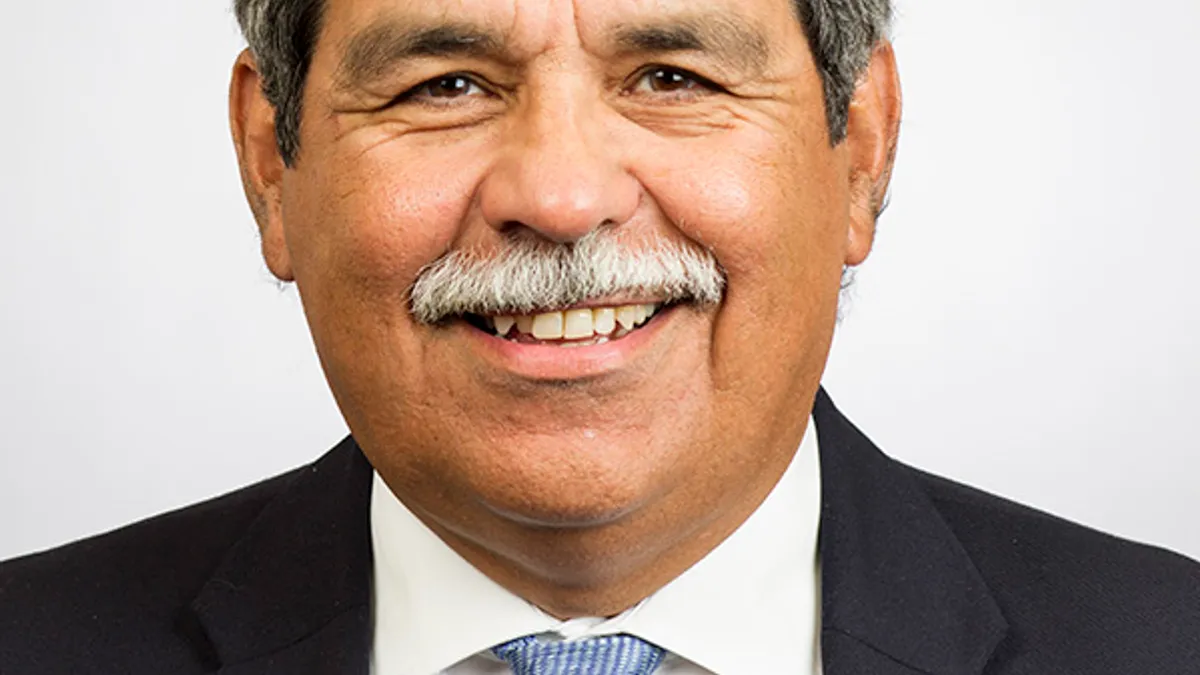

Michael Hinojosa is no stranger to the superintendency or the Dallas Independent School District. Not only is he one of the system's former students, but he's also in his second stint as its leader.

After a rapid ascent to administration led him to the district the first time around, and facing "two big college tuitions" as his sons headed to Ivy league schools, he left for a job in suburban Atlanta's Cobb County School District. He eventually retired and returned to Texas, doing some consulting as he and his wife cared for their aging parents. But churn in Dallas eventually brought him back to the district's top role.

His second stint has seen buy-in from educators and the public on a handful of often-controversial issues — the most notable being performance pay for teachers, which was a central issue in the strike against Denver Public Schools.

"The good thing is that our teachers are being recognized for the impact that they have. And it's in Republican states and it's in Democrat states," Hinojosa told Education Dive. "People are recognizing that teachers need to get rewarded and paid more," adding that "people also need to pay attention to what is the most effective way" to address the issue.

During the conversation, Hinojosa discussed the district's performance pay system, his biggest challenges upon his return, how he got voters on board with a $1.6 billion bond issue and how the district is reimagining its schools.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The following interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

EDUCATION DIVE: What were the biggest challenges you faced upon your return to the district, and how did you overcome them and establish trust?

MICHAEL HINOJOSA: I followed the same entry plan [as] every time I've gone into a district. In the first 100 days, I do a lot of listening. There was a lot of turmoil and churn in Dallas at the time. The teacher turnover rate one year was 28%. Over 50% of principals were new. There was complete turnover of senior staff. There was a lot of churn and a lot of negative publicity. In fact, the board members told me there were media trucks at every board meeting the three years that I was gone. But there were some good things that happened.

I asked 100 people 10 questions. Then, I came back in 90 days, after I did that listening tour, and reported to the board that this is what the community wanted to hang onto. Some of it was controversial. They wanted to stop losing teachers. They wanted to stop losing principals. They wanted to stop the negative publicity the district was under during the previous administration. So, part of that was listening to everybody and figuring out what was working, what wasn't working and how we needed to improve things, and just putting a calmness into the district.

Since I had grown up here as a student, I was here as a teacher, and I had been the superintendent before, I knew the community, I knew the city, and I knew a lot of the players. I was very fortunate that I was a known commodity, but there was also the fact that I came in and listened to 100 people from every perspective. Some of the questions were, “If you were in my shoes, what would you do first? What do you expect of the superintendent? What three things do we need to do to make this the best district in the country?"

I took all that information and put it into emerging themes. That's what I started tackling.

Given that teacher evaluation metrics and performance-based pay systems can be a touchy subject in K-12, how do you sell an idea like the Teacher Excellence Initiative and gain educators' buy-in?

HINOJOSA: That was the biggest challenge. In fact, very few districts have done this and done this well. Washington, D.C., was a leader, [but] they've had four superintendents in the past four years. Denver was doing pretty good, but then that became a flashpoint in their strike. Tennessee has tried to dabble in it, and so have a few other states. The ideas that were brought by the previous superintendent were very bold, and it’s to pay the best teachers more and to get the best teachers to go to the toughest schools. And I was skeptical early on. But one of the things the board told me when I came back was that they really liked the plan. I needed to try to figure out how to make it work.

One of the best things about the plan is that teachers were observed very often. Every teacher had to have 10 "spot observations" every year. It's kind of like if you're driving down the freeway and there's a police officer on the road, and even if you're not speeding, you take your foot off the accelerator because you respect the law. And if that many people were in your classroom, teachers had to be on point and had to be teaching. However, a lot of teachers felt like they were micromanaged and we had gone over the top. And we were over-testing. We were testing kids in kindergarten, 1st grade, 2nd grade and in music. We've given paper and pencil test in music and choir and PE.

What I had to do was back off of some of those things. Then, we differentiated the spot observations. If you were a high-performing teacher, you got less spot observations. If you were a novice or lower-performing teacher, you still got all the spot observations. I had to tweak it along the way, knowing the board wanted it and the reform community wanted it, but that the staff was against it — a lot of teachers. I was very skeptical.

So about year two or three, I had this meeting with my senior staff when the light bulb came on. I had the grand epiphany. While we had one year at a 28% turnover rate, we had now normalized to about a 12%-15% turnover rate. But we were keeping 95% of our highest-performing teachers based upon their effectiveness level.

That was when I had the grand epiphany that this is now worth it. If we’re keeping our best teachers, then we’re having the right kind of turnover. [But] my other big worry was how [to] pay for this promise that we've made.

What we did to make things work is in Dallas, nobody got a raise for three years, because we had no new money coming in at that time — except for our highest-performing teachers. Then, we funded some of our other key initiatives, like pre-K, public school choice and P-TECH, our collegiate academies. Those four things got funded because [they] needed new money. And so we were able to keep it alive.

That's how we started building support and ownership with the teachers, because our highest-performing teachers were getting more and they were staying. We went to the voters, and the voters passed a 13-cent tax increase to fund our strategic initiatives. Now, I've got funding for the next five years for these initiatives, and if we have a good result in this legislature — which is looking pretty good right now — we can extend that for another couple years. It was very dicey, but we're now in a very good place. We've gone from 43 schools that were under state watch for takeover down to four. And all of those are brand new. We're starting to have a lot of success, and the community has supported us with a referendum.

Speaking of voters, in 2015 you had to sway them on a $1.6 billion bond issue to improve the district. What went into pitching and selling that to the public?

HINOJOSA: Well, that was also a plan that had been developed prior to my arrival. In my 24 years as a superintendent, I've always taken referendums to the community. And I've been very fortunate that we've never failed one. The board asked me in my interview if I'd be willing to go for a bond, because they hadn't had a bond since I was here in 2008. This was 2015, and the disrepair of the buildings was pretty obvious.

I took the plan that had been developed by the previous administration, and we took it to the community in November — it passed by about 57% or 58% — to try to deal with some of the aging buildings. We have buildings that are over 100 years old, and we have a lot of enrollment shifts. Part of [the plan] was [also] to fund some other specialty schools. We did that, and later, we discovered there probably wasn't enough community input and staff input on developing that plan. So, we've modified it. Now, we've come up with a master plan for facilities and technology, and we plan to go back to the voters in 2020 for another bond. But this one's going to have a lot more stakeholder involvement in it.

I read about how Dallas is setting itself apart by reimagining schools with specific academic themes. How important is that sort of approach in an era of increasing school choice?

HINOJOSA: That's a huge question. And that's why public school choice became one of our strategic initiatives. Our market share was down, and that became one of our goals — to improve our local market share. We know charter schools are not going away. Private schools have never gone away. We even have to worry about home schools.

So, we decided to do a public school choice initiative. We have innovation schools and transformation schools — startup school[s] where you can start as a certain grade level [and theme] — such as STEAM, a Montessori school or a personalized learning school — that we start from scratch. We have quite a few that we've done. And we also have innovation schools. Those are neighborhood schools where they can reinvent themselves with a theme such as personalized learning.

One year, we had 4,000 applicants from parents who don't send their kids to our schools, but they applied to the specialty schools. We've also had enrollment shifts because we've lost so many kids to charter schools. Some of the schools that were full before now are empty or half-empty, so we've had to combine and repurpose some schools.

But now, we feel like we're on the uptick, we have a lot of interest from our community members, and we're reimagining. We're doing performing arts schools, and Toyota and Southern Methodist University are partnering with a STEM school for us in an impoverished community. All of a sudden, because we knew we were facing a big challenge, we decided to come back with some innovative approaches. And it's starting to resonate in our community.