Lessons In Leadership is an ongoing series in which K-12 principals and superintendents share their best practices and challenges overcome. For more installments, click here.

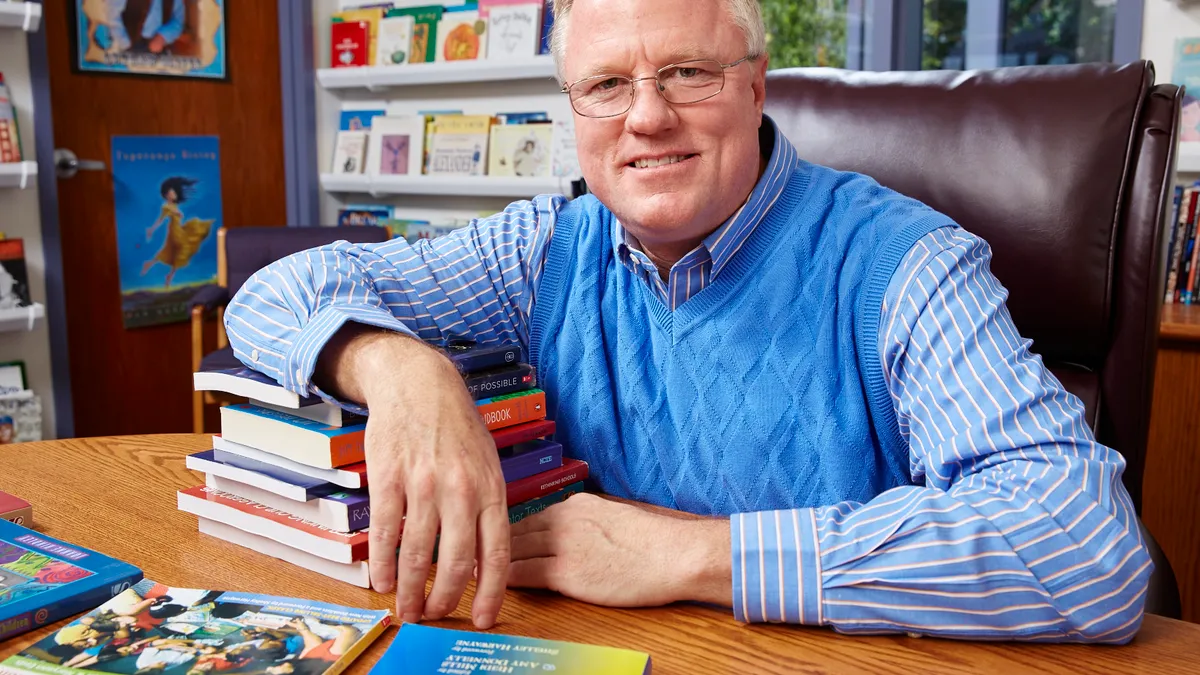

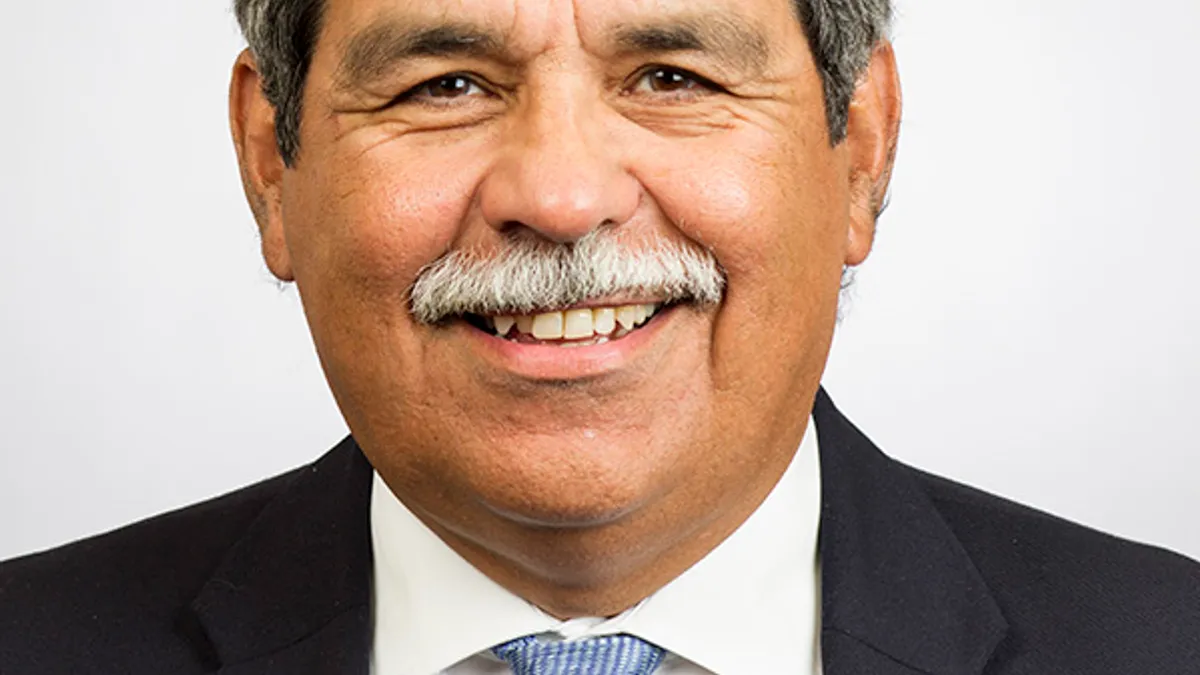

In May, Rick Surrency, superintendent of Putnam County School District in Florida, traveled to Finland with seven other U.S. educators as part of a Fulbright Finland Foundation cultural exchange program. During the trip, Surrency and his peers had the opportunity to tour schools across the Scandinavian nation, which regularly tops international education rankings.

“Finland's got the numbers to prove it on the PISA exam, which is given to 15-year-olds across the world every three years,” Surrency told K-12 Dive. “Finland has continued to take the lead in that way above the United States. So there's some things they're doing that I think we need to really sit back and take note of.”

Over the course of our conversation, Surrency shared his takeaways on how Finland handles playtime, standardized testing pressure, teacher strikes, and recruitment and preparation — as well as how he’s putting lessons learned to work in his own 10,000-student district.

K-12 DIVE: Much has been said of Finland’s education system over the last decade, but what stood out to you most from your experiences touring the schools there?

RICK SURRENCY: One of my colleagues talks about how [Finland’s education system] has a certain ethos, and it's kind of like the students and the teachers there seem so content and so relaxed. Whereas, over here we're rushed for time and there seems to be that undercurrent of anxiety. I just noticed there was a lot of contentment there. Children really enjoyed being in the school and really connected with their teachers.

We went into a number of elementary schools and, first of all, everybody had to take their shoes off because they spend so much time playing on the floor and just interacting with their teachers. But the thing that really stood out is that, in the elementary schools, every single hour, they schedule 15 minutes of time to go outside and play. That's after they have a 45-minute lesson. They really believe in the idea of play and engaging with nature.

The other big thing is students do not have to take standardized tests. There is a test they take at the end of their career, but they measure student progress by the teacher's observation. And the teacher is considered to be the expert, kind of like how we look at doctors and lawyers and engineers who are experts in the field. The teachers themselves can actually tell you every single student and their progress. They don't rely on, necessarily, a standardized test. They just ask the teacher.

To be a teacher there, the preparation is very extensive. They have to have a master's degree, [and it’s] very highly selective — 10% of their teacher applicants get into the teacher university center. But it's almost counterintuitive to what we're facing here in the United States: Whereas we are almost watering down our profession just to put people in the classroom, they are actually turning away people who want to be teachers. And it's because it's such a revered profession over there.

When students get into high school, they have a choice of what school they go to based on their GPAs. And once they get in there, they really kind of tend toward a career track or a university track. But that is really kind of gelled when they take their one [standardized] exam at the end of their K-12 career, and they call that a matriculation exam.

We actually interviewed a number of Finnish high school students. The matriculation exam is extremely extensive, and it takes like five or six days to take the exam — one subject at a time per day. But that will determine whether they go on to a college or to a career track. And that's really what students work for is passing that matriculation exam.

Once they do that, it doesn't necessarily mean they can't change their mind. There is a lot of flexibility, but again, these students are really highly motivated. Many of the students we talked to took two or more foreign languages. The takeaway I have from those students is they are so motivated to be successful. And one thing that really stood out to me about the entire school system is they really value equity over excellence.

What I mean by that is, I think in the United States, we are so focused on trying to be No. 1 and trying to outrank other schools and other states. It's such a race, it's almost like a zero-sum game, if you will. There's a winner and there's a loser. Over there, everybody is a winner. They really spend a lot of money on providing basic necessities for students to make sure that they have what they need. And because of that, students excel because they have all the basic things they need in life to be successful in school. So they achieve excellence through equity, whereas it seems like in the United States we have winners, but we also have losers.

Let’s circle back to playtime. I’ve read about the benefits of giving students playtime throughout the day, especially at the elementary ages, because it helps release pent-up energy, allows them to focus more, and supports social-emotional growth. Can you tell me more about what you noticed on that front?

SURRENCY: First of all, I noticed when they let them out to play, they even let them out to play in the rain, and even in the extreme cold weather, because they're used to that. There’s such a focus on them playing and having that time that I think it does reduce that anxiety. And it helps kids kind of build those leadership skills. You can see leaders emerge on the playground.

I stood there and watched them play, and those kids are so intent on playing that there really is a method to that. I think we can learn so much from the idea our kids don't necessarily have to spend time in class nonstop to get smarter.

It's almost like less is more in Finland. Over here in the United States, we're really focused on that pacing guide. We've gotta be in a certain place by a certain time so we can get some kind of exam. That's a completely different thinking model than over there. They're really very much into flexible teaching.

Some kids may not be on grade level, and that's OK. They actually have time where they'll work with them separately and help catch them up. But it's almost like there's not a big stress on that. I think we in the United States are so focused on that industrial age model where kids are going through a grade and they have to be at a certain place like on an assembly line. And if they're not, then they're not OK.

What are we doing to our kids? What kind of anxiety are we creating, especially in our young kids, that if they're not measuring up by a certain time, they're almost an outcast? I think that creates so much stress on our kids, and the mental wellbeing of our kids suffers because they feel ostracized if they're not at a certain place.

Regarding teacher respect over there and the amount of prestige given to the profession, but juxtaposed with there also being a teacher strike going on during your visit, did you notice any differences in how teacher strikes were approached?

SURRENCY: That's an interesting question. It's almost like if teachers go on strike in the United States, they're the bad guys and they're taking away time from our kids or they're wanting more money. Over there, when we talked to people, it was like, “Hey, teachers are on strike. They deserve whatever they're asking for.”

With them being a national system, they actually had a rotating strike. They didn't strike across the entire nation. They rotated it to different cities. The idea was teachers really deserve more, and it was supported by the general public. It wasn't looked at as a negative, like we might look at it over here.

I think that level of respect is something we don't necessarily see here. I'm not suggesting we go on strike here, either. As a matter of fact, Florida's a no-strike state. But I'm just saying [we need] the attitude that, “Hey, our teachers are out there. They're our heroes. Let's see what else we can do to help them in their profession.”

You mentioned Finland’s matriculation exam and how it helps identify students’ aptitudes for college or career tracks. Do you think there's a lot U.S. schools could learn from that as far as how to improve career and technical ed or vocational tracks versus college as the be-all, end-all goal for post-high-school?

SURRENCY: They truly focus on kids who are in the career track. They're really big into internships, and kids who are in that track actually spend a considerable amount of time working in businesses. They truly have that hands-on, real-life experience.

The other thing that goes along with that is those schools receive funding based on the level of those internships. They actually talk with those businesses and they get input. The schools have a vested interest to make sure those kids have those real-life experiences. It's more than just classroom [learning]. They physically put them into those working relationships with those area businesses.

When they take those matriculation exams, they are truly prepared to pass those tests, and it’s the same thing with the colleges when they go to the college track. Those kids take very rigorous courses. We interviewed a number of those kids, and believe me, they really spend their entire high school career doing nothing but focusing on what they need to do to pass that matriculation exam.

From everything you learned during the trip, what would you say are some of the biggest ways so far that you've been able to implement those lessons in your own district?

SURRENCY: Coincidentally, when I came back, we actually set up a project where our leadership team here did a very strategic way of reaching out to our employees and sending personal notes — you know, trying to be more hands-on and really just trying to show respect and trying to show that the teaching profession is an honorable profession. I think we as leaders, instead of being the overseers and managing people, need to lead people. And we need to be servant leaders and show the respect that our employees deserve.

There may be some teachers or other employees who maybe aren't cut out for this, but I think our role here — and I'm looking at myself now — is to try to be the person who sets the lead on setting that culture of mutual respect and really helping teachers to be successful instead of just, “Hey, if you're not good in your first year, we're gonna kick you out.” We're dooming ourself [if we don’t] because we need to be able to go in there and work alongside that person and help them be successful.

That's exactly what we've done here in Putnam County. I've hired about five or six full-time teachers who do nothing but mentor young, inexperienced teachers. Again, that costs money for us to do that, but you know what it does? It helps them to become better educators, and it helps them to learn the craft. Whereas in Finland, they might do a lot of that prior to becoming teachers, we almost extend their college degree once they get into the classroom.

We provide that face-to-face, side-by-side learning with those teachers, with our teacher mentors, and our retention rate has gone from like 63% for retaining teachers per year to, in the last three years, we've increased that to the mid-90%. So it is truly working, and that teacher retention effort, again, is trying to build that respect in teachers and support them.