Lessons In Leadership is an ongoing series in which K-12 principals and superintendents share their best practices and challenges overcome. For more installments, click here.

Located in the northwest suburbs of Chicago, Maine Township High School District 207 has earned a reputation for high student performance and strong teacher retention — both of which can be credited to the district's commitment to an "all-in" approach to teacher coaching and professional development.

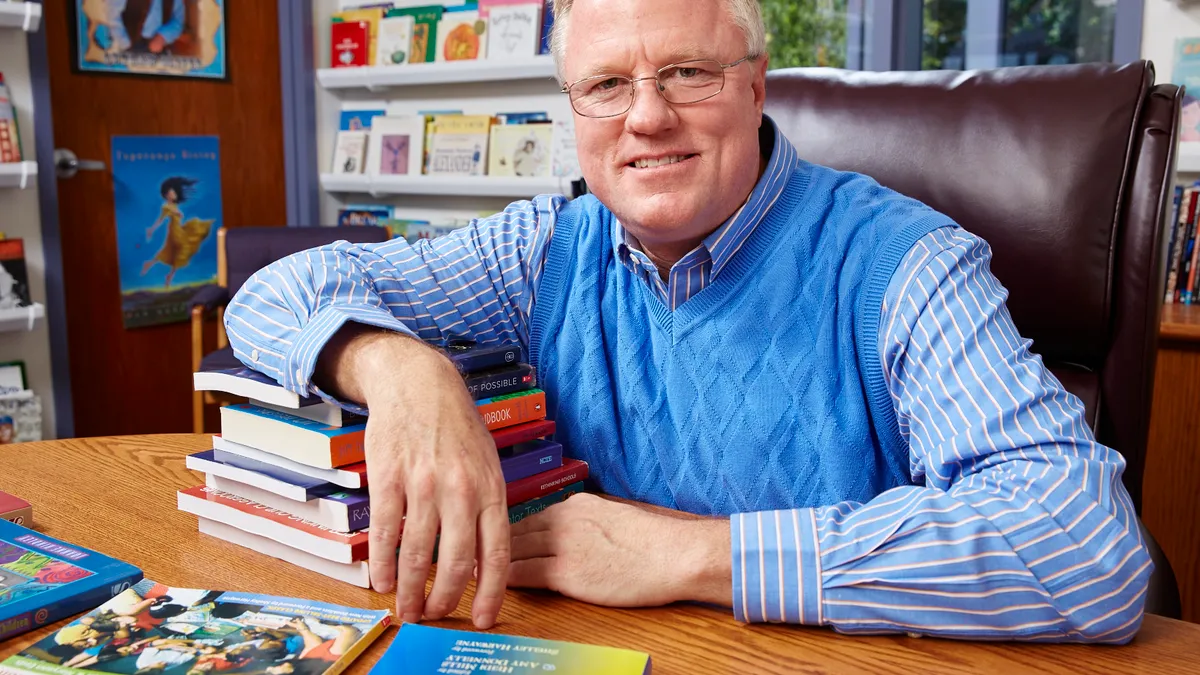

"There's a lot of things the superintendent has to pay attention to, but I will always believe strongly that the core mission of any school building is to create great learning conditions," Superintendent Ken Wallace recently told K-12 Dive. "I also believe strongly in and try to build conditions where we pay very careful attention to the learning conditions for the adults. That's one of the core mistakes that is made — we put all of our attention into focusing on student learning and not nearly enough on the need for continual processes for real adult learning."

Over the course of our conversation, Wallace shared his thoughts and advice on the importance of teacher leadership roles, gaining principal buy-in, building district partnerships and more.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The following interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

K-12 DIVE: What’s at the core of your district’s approach to strong coaching?

KEN WALLACE: When I got here in 2005, we had started training with Roger and David Johnson, who run, or did run, the Cooperative Learning Center at the University of Minnesota. Cooperative learning is one of [John] Hattie’s high-impact strategies.

They have a “train the trainer” model, so we would send teachers out to University of Minnesota. They would be trained, and they would come back here, and they would train others to use cooperative learning. We actually have more “Johnson and Johnson” trainers than anybody in the world, and that's according to Roger and David Johnson.

When I got here in 2005, I'm a “trust but verify” person, so I brought an outside group in to do an instructional audit. What we discovered in 2006 and 2007 is that though we had trained well over 300 staff members in cooperative learning, almost no one was using it.

That is actually the problem.

We were doing training the conventional way, which is “Let's bring people into a workshop. Let's discuss all the mechanics of cooperative learning and maybe practice some of the strategies a little bit in the workshop.” And then expect you to go change from your traditional way of teaching to something messier and much more complex.

Even if people went back and tried it the first time that it got a little loud and a little messy, keep in mind that was at a time where if classrooms are loud, that often could be considered a bad thing. And because cooperative learning has groups of students working together and they're talking and they're problem-solving and they're fulfilling different roles, it's the way real learning looks like. So our people went back and they simply stopped trying to do it.

But there was a group of people who were using it well — our trainers. And that was that “a-ha” moment. We remember 10% of what we hear and 25% of what we see and hear, but 95% of what we teach.

So beginning in 2007, as we were doing our cooperative learning cycles, we added coaching into those cycles. That really was the beginning of the journey to all-in coaching, and it was to address what was an easily identifiable problem with our model, which was we were doing standalone training.

The research is abundantly clear on this. If you do standalone training, your implementation rates seldom get above 10-20%. You're lucky if they get to 20%. If you add coaching cycles with the training, you can get up into the 80% and 90% implementation rates.

When we added coaching in the cooperative learning cycles, we saw improvement in those people coming through the cycles and implementing cooperative learning in their classroom.

Since we've gone to all-in coaching, we also have a four-year new teacher cohort. When you come to work for us, we put you through a four-year cohort with all of the high-impact strategies we want you to use. We not only train you on those, but we coach you on those, because each of our teachers, [whether they’re a] new teacher or 35-year veteran, all have an individual coaching plan.

How important is it to build those coaching and leadership roles in, not just from a retention perspective to give classroom teachers a role to grow into, but from a standpoint of making sure training sticks better because maybe teachers are a little more willing to embrace something they're learning from a peer?

That's been a design element involved in this from the beginning. We bring outside experts in, but it's to build internal capacity. And at the end of the day, you want powerful staff. From a design thinking standpoint, we have set out to try to create conditions in which every one of our teachers can be an empowered learner and an empowered leader.

Think back to what we discovered with our cooperative learning trainers: They were the only ones actually using it. Why? Because they were teaching it. So we have constructed conditions to open up pathways for more of our teachers to ascend into those leadership roles. In addition to our instructional coaches, virtually all of our professional development is led directly by District 207 teachers. So to your point, it's peers.

We're constantly ideating on how to continue to open up paths. How do we find leadership opportunities for every teacher? We have five instructional coaches in each building. As those spots come open, there's a lot of competition for each of those spots — which is a good thing.

We want people to see that as having a lot of caché, that it’s a true teacher leadership position. Those people, because of the way we've evolved our system, are not just leaders of teachers, but leaders in the building. Their input for the administration team in the building is significant.

We've been intentional about making sure all of our teacher leaders are really in the feedback loop. And frankly, a lot of the decisions that get made today in this district have direct input and recommendations from teacher leaders. We've seen a ton of it just even through the pandemic where we could just reach out to teachers [and ask] “What do you guys think?”

We've [also] done some mechanical things. We've got an agreement with our union to have coaching plans for every teacher. That's a thing that I get asked a lot about: “How in the world did you do that?” We're in Chicago, so it's not like we're in a place where there's not strong unions, but we built a good relationship with our teacher leadership in the union. And at the time, we had people who were very interested in the teacher leadership model.

The other thing that's so crucial is we made a promise that in our coaching, our teacher leadership would be safe and firewalled from evaluation. If you're being coached as a teacher, I want you to know your coach — unless you're doing something immoral, illegal or unethical that's a reportable offense — is someone safe for you to confide in and help work through things and lower the cost of failure for you individually as a teacher. [It’s] to allow you to not be worried about trying to be perfect all the time and just focus on learning and getting better.

When it came to implementing this approach to professional development, what steps did you take also to adjust principal professional development?

The areas of pushback in this are not always just from teachers. Sometimes they're from your administrative team. We’re a department chair district. So we've got department chairs that run their departments throughout our high schools. Some of the initial pushback was on that end, because the conventional thinking was the department chair should be the one who coaches teachers. And there's elements of truth to that.

But in the purest sense of coaching, it absolutely is essential that someone's true instructional coach not also be their evaluator. One of the things that's important in this cycle is making sure that we reduce the fear of failure. And if your coach is also your evaluator, it's almost impossible to remove this idea that this person is also the one that's going to be rating me.

In all of the training that we do, our principals and our instructional leaders are part of that. They are right in there, side-by-side with the teachers. In that way, what we've tried to do is really make this a very flat system so when we're talking about differentiating instruction, when we're talking about blended learning, when we're talking about anything from a pedagogy standpoint that we want to see in a classroom, we expect our administrative staff to be a part of that and to help be a part of that.

Given the partnerships the district has had with Google providing hotspots, with coaching like you have now with Northwestern and so on, what advice would you give to other district leaders when it comes to building strong partnerships with local institutions or other entities to support various initiatives?

The first advice is to start by talking to some of your local universities. Take a generally well-known problem in education: a present and looming teacher shortage. That's a topic that right away has a shared interest between you as a public K-12 school district and your local university or your state university. That's a shared problem. State universities, private universities — they’re all seeing schools of education enrollment go down.

There's a lot of reasons for that, but I'm interested in solutions. For example, we have a future teacher pathway pipeline where our students are taking their initial college courses in our schools, [and] they’re getting field experiences and internships to confirm they really want to go into teaching. Our seniors in high school that are in these courses, a high percentage of them — and I'm talking 99% of them — actually ended up going into teaching. We've been at it long enough that they're now out in the field teaching.

When you approach your universities, they're interested in that. They're interested in helping you build that, and they're also interested in the success of their graduates.

If you've got lower enrollment in schools of education, it's even more important to have super high retention rates. So when you add the element of coaching into that cycle, you have a mutual interest there. You’re providing, hopefully, a better framework to find a teacher pipeline for your own school district, but you're also doing something really important for the university, which is to help drive their retention rates up.

And frankly, you're doing something really good for the teaching candidates themselves. You're helping them uncover those same rookie mistakes we've all made as teachers, but you're doing it with a trusted, safe colleague in real-time and coming up with solutions so you're not suffering through that in isolation without some really good feedback.

If you think about the conditions you'd want to create for having better schools and having better experiences for teachers, it really is that. You're going to find very quickly there are areas of shared interest.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards