Lessons In Leadership is an ongoing series in which K-12 principals and superintendents share their best practices and challenges overcome. For more installments, click here.

Recent research shows despite a significant increase in numbers, educators of color have continued to represent less than 25% of the overall teacher workforce over the past 30 years, and U.S. Department of Education data shows that less than 2% of the nation's educators are black males. But the impact the sheer presence of these educators can have on the success of students of color, even if they don't directly teach them, is significant.

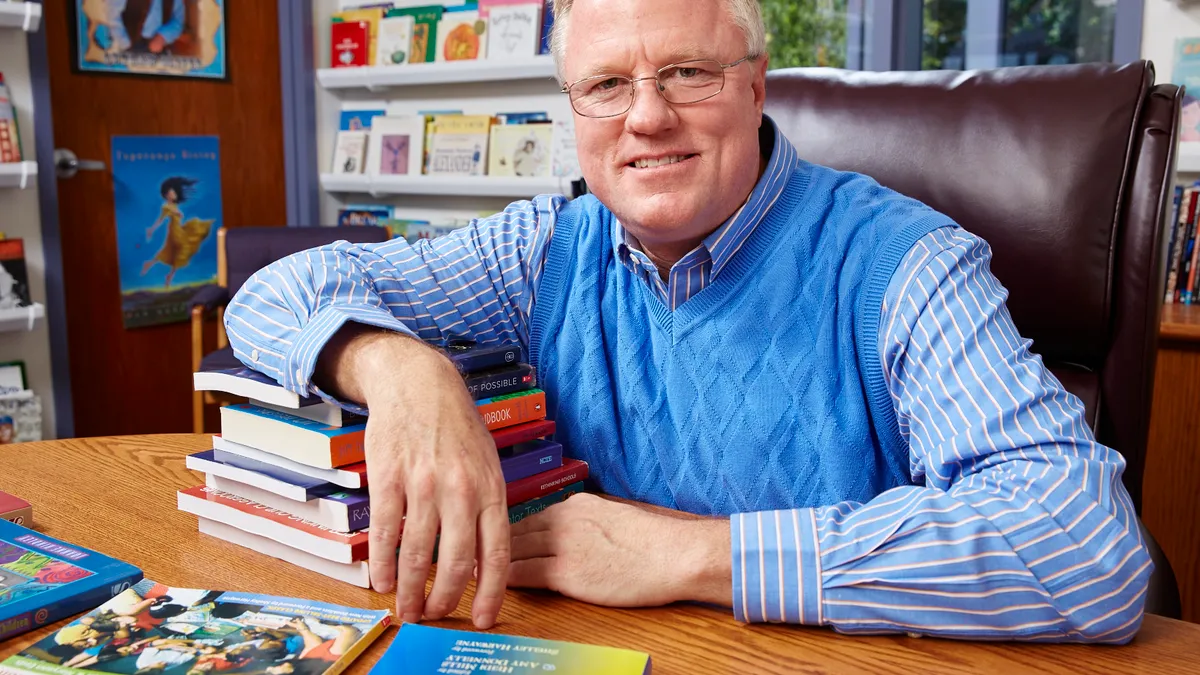

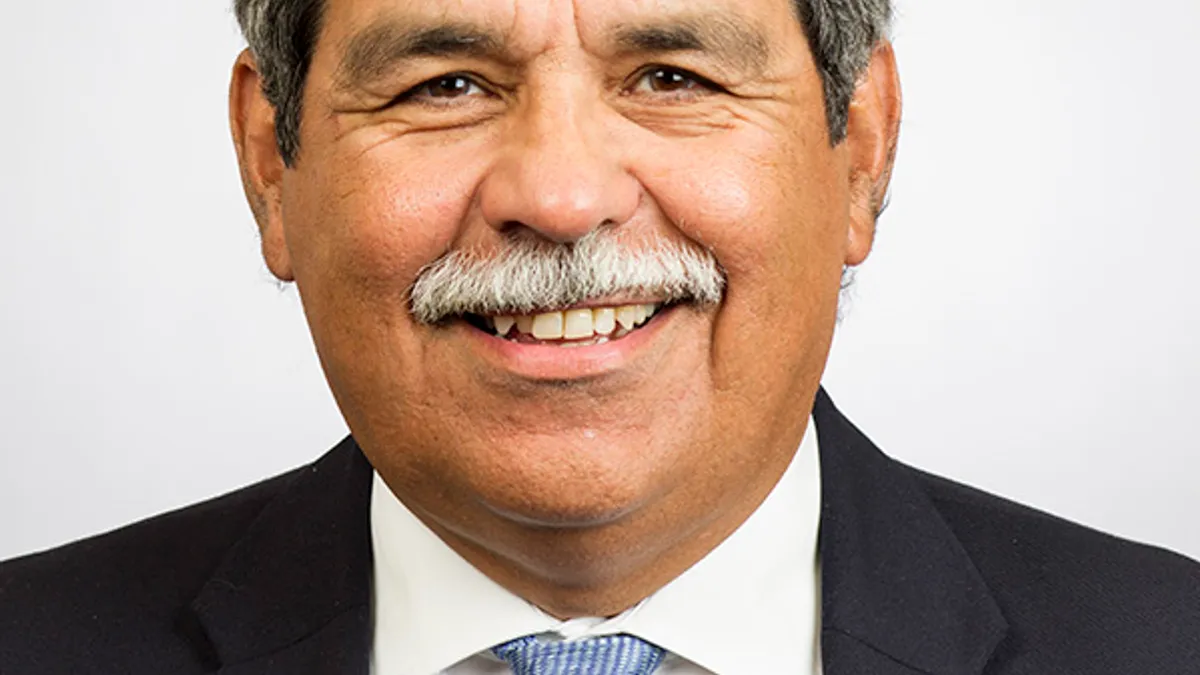

Founded in 2003, Eagle Academy was the first early childhood public charter school in Washington, D.C. Located in the southeast neighborhood of Congress Heights, the school serves a high population of students whose socioeconomic backgrounds put them at an instant disadvantage to their peers in the region. It's a challenge that Pre-K and Kindergarten Principal Melanie Leonard and Grades 1-3 Principal Royston Maxwell Lyttle welcome head-on.

Education Dive recently visited Eagle Academy for a discussion with Leonard and Lyttle on the importance of shattering stereotypes, providing diverse role models in school buildings, managing student trauma and easing the transition from pre-K into the early grades.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The following interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

EDUCATION DIVE: Research has highlighted the importance of how schools handle the transition from pre-K and kindergarten into the 1st through 3rd grades. How beneficial is it to have pre-K under the same roof in that transition?

MELANIE LEONARD: I think it's very beneficial. Ideally, all of our students are receiving the same quality education at the pre-K level, so they're moving into kindergarten and through 3rd grade — the formalized years — with the same information. I mean, obviously, we have varying performance levels based on when students come in, but because we have them all in the same school, and we're all utilizing D.C. early learning standards for the lower school and then Common Core for the upper school, they align. We are preparing students for kindergarten through 3rd grade, and we know they're all entering having received the same information.

Whether they all understand the same information at the same level, it's helpful that there is a standard knowledge base that they have — instead of when they're coming from various day cares, and one's coming from home, and one is coming from here and one is coming from there. It's hard, then, to make sure that you are giving every child what they need. But here, ideally our students are moving from pre-K to the upper school having received the same information.

ROYSTON MAXWELL LYTTLE: With the same curriculum and just the advantage of having the students' previous teacher in the same building. So when they're in 1st grade or 2nd grade, it's like, "Hey, do you know what is going on with Johnny? What did you experience last year with Johnny or Johnny's parents? How supportive were they?"

Everything that a teacher would need to know from the upper grade levels, we have that experience in background information from the previous teachers. We also have it where we had a couple of kindergarten teachers this year loop up from kindergarten to 1st grade, so they moved with their students to the 1st grade level. So it's a benefit to have one school with pre-K to 3rd grade.

Do you all have home visits with students' families as well?

LEONARD: We don't have a system for home visits, but we certainly conduct them for students who either have attendance concerns, or if there is a concern of neglect in the home or a parent reaches out to us and they need assistance monetarily. Or for transportation — sometimes we require a home visit to provide the resources for them.

We do home visits if needed, but we don't have a regular system where every teacher is required, for example, to do home visits. We've done pilots with that in the past. I think two years ago, we did a pilot with a lower school teacher and an upper school teacher where we wanted them to do systematic home visits throughout the course of the school year, and we do think that it helped to improve the relationships and build that home-school connection. But in terms of requiring it school-wide at this time, we don't. But we see the benefit of it.

LYTTLE: Building relationships is the most important thing, and a lot of our teachers, while it's not mandatory, they do spend weekends doing special functions — if it's a birthday party, a child sporting event or a special activity like a performance. Teachers do volunteer and go and support those families.

We have a parent liaison family engagement coordinator who works closely with parents to take some of that stress from our teachers, who does home visits and meets parents at their houses. And then we have responsive classrooms.

Our teachers are trained in responsive classroom approaches, how you respond to students' behaviors so that suspensions are only our last alternative — and that's with injury with grades 1-3. Teachers have to know that, and parents will learn that a lot of behaviors are age-appropriate. We haven't suspended any pre-K [students], because that falls into that age-appropriate behavior, and the training teachers receive with responsive classrooms helps them understand what's developmentally appropriate.

There's also been a lot more effort nationwide just to understand how certain behavior stems from students' backgrounds.

LEONARD: Certainly. So we have a school climate position here, and she is getting ready to go to a four-day training about trauma-informed care, because a lot of our students experience trauma in the home. Obviously, their response to that can sometimes play out negatively with their behaviors in the classroom, but we need teachers to understand what has happened to students, what it does to their minds, what poverty does to their minds, and then what we can do to combat that, instead of always trying to address it with punitive consequences or discipline all of the time.

I think we're really trying to do a lot of work with our teachers to understand our children's backgrounds and environments, and the implication of that on their behavior, what they know and what they don't know so they can address them more appropriately.

LYTTLE: A lot of our students come to school with social-emotional baggage that they bring from home to here. I've been in a school where students — and I'm saying students around 10-15 — experience some type of death in their household, and school is the one thing that's normal. We have to [be a presence] in their life that's consistent. We have to ensure that they receive that social-emotional support they need, whether it's death, homicide, incarceration. Last year, we had a student's father who was killed right outside of the property.

LEONARD: After dropping his son off at school. So they experience serious trauma.

LYTTLE: Yeah, so I listened to him. He said he has to come to the place where his father was killed. When you hear about social-emotional or behaviors, you really have to understand where the problem is. Students are not coming to school to be "bad." It's just they experience life challenges differently than students who normally don't provide school behavior issues.

You mentioned that you had some kindergarten teachers who moved up into 1st grade. Even in scenarios where teachers don't follow students from one grade to the next, how important is it, especially with school being a consistent experience in students' lives, that they see familiar faces from year to year?

LEONARD: I think it's very important. Sometimes this is the only stability provided for students within our school. For them to see people they know, for them to have relationships with people year after year — where some people stand in almost as family members for some of our students — they need that. And even if they don't necessarily connect with their current teacher, there's someone in the building in the adult world that they have a relationship with. I think it's very important that they see people they know and they trust and they know are going to keep them safe, because some of them don't always have that in their homes.

On a similar note, with student bodies becoming increasingly diverse, how important is it for students to see people in various positions of authority who look like them, who they can see as role models — especially as far as breaking stereotypes that they might have ingrained really early on in life?

LYTTLE: One thing with diversity, black males represent 2% of the teaching population. So, the odds for an African-American boy — and, first of all, I acknowledge that physical education teachers are teachers, but teachers that provide direct instruction as far as science, history, reading, math — [are that] they will go the majority of their educational experience without having a black male teacher.

We did a push to hire more black male teachers. Last year, we went from two in the school as far as pre-K through 3rd grade to this year having seven male teachers. This year, a student we have who's quiet, who has a male teacher, told the teacher and his mom that he wants to be a teacher. So you have to be able to experience and see it, see an adult male that looks like you model how to read, model the curiosity to think of a hypothesis and walk male students to think outside of sports.

LEONARD: Or music industry as their only alternatives.

LYTTLE: And show them that it's cool to learn. Growing up to hear their teacher who looks like them read a story to them might be minor, but the majority of kids will always see a white male teacher or white female teacher or black female teacher do it. And there's nothing wrong with that. They're doing an excellent job. But the chance of them seeing a black male teacher is slim. So building relationships, having that person that looks like them, it's very important in their lives.

I was just reading earlier today that, I think it was since 2006, the number of educators of color has increased by 300,000 or 400,000, but overall they're still only a quarter of the overall teacher population.

LYTTLE: Especially in early childhood. This year, Ms. Leonard hired two male teachers for the pre-K level.

LEONARD: I don't think I've had a male pre-K teacher before. I'm excited about that. And it's not that black children need a black teacher. That's not what we're saying. But I do think it's good for them to see people of color in various roles. They're teachers here. They're department coordinators here. They're speech pathologists here, psychologists. There are a variety of career paths that they may not know of or may not hear of in their homes that they are directly in contact with here at school, so I think that opens up the world for them.

Just the presence of having someone in the building who looks like they do is beneficial in getting them to think outside of that box.

LEONARD: Correct, because most of them say they want to be an athlete or they want to be a rapper, because that's what a lot of them see on television. For a lot of them, television heavily influences what they know and what they aspire to. I'm glad that here, we're able to show them — not that there's anything wrong with football players or rappers — there are other alternatives, because there are not a lot of slots for NFL players and NBA players, and everyone is not skilled to be able to do that. They have to think of what other skill sets they have and understand what options are there for them that are realistic.

Overall, what would you say are some of the biggest challenges that you deal with day to day?

LEONARD: I think the fact that [because] a lot of our students have witnessed trauma or have been affected by trauma, we do have a lot of behavior challenges that make it hard for teachers. Teachers enjoy teaching, but they do have to manage behavior before they can teach.

If the children are not able to be in a structured setting and be attentive, listen to the information, or understand it because they're hitting one another, or running or screaming or yelling or climbing or fighting, that makes it difficult for the teachers. I think the hard work for the teachers is managing behavior in their classroom, building relationships, and setting systems, routines or procedures in place first so they can then teach students to achieve a higher level.

Some of our preschool students come in 18 months behind their peers, so that's a challenge as well. Some of the prerequisite skills that you think a child would have coming into school — in terms of oral language or alphabet knowledge or simplistic things like walking and fastening up their coats and just, you know, self regulation — they don't have. So teachers are spending, especially in the lower levels, a lot of time being the parent or helping students with social skills. Those are things that are necessary before you can really teach a student to be able to achieve at high levels.

LYTTLE: Another of the challenges is just to break down the stereotypes. What we expect from the staff here is the same expectations that any school has. That same high-quality education is what our students require and need. And to provide them with anything else is doing them a disservice.

LEONARD: Certainly, a challenge with our staff is mindset — shifting mindsets to understand you should have high expectations for all students. What you require from a student in a suburban area is the same thing you should require from a student here, and if they can't meet that requirement, it's your job to help them understand the raised standard and help them reach it.

You have to believe yourself. "They can do it. I can teach that child to read no matter the challenges. I am here to do this work and it's hard, but I can do it. They can learn."

We had a gentleman come at the beginning of the school year this year, Eric Jensen. He wrote a book called, "Teaching With Poverty in Mind." He came for three days, consecutively, to talk about shifting your mindset, and I think that was a good starting point for all of the staff, to hear the statistics around poverty, what it does, what we can do to change it, and what are specific strategies we can do to help students. Because, yes, that is a challenge, the mindset.

LYTTLE: I know our CEOs would say [a challenge] is just to receive the same funding that D.C. public schools receive, because you know, like I said, our students require so much. We do reach out and try to build partnerships for wraparound services for our students with social-emotional support. For example, First Home Care and Primary Project. In order for us to provide those resources, if we don't build partnerships, it comes out of our funding — which is less than a traditional public school.