Lessons In Leadership is an ongoing series in which K-12 principals and superintendents share their best practices and challenges overcome. For more installments, click here.

With nearly 64,000 students, Virginia Beach City Public Schools — the fourth-largest school system in Virginia, and located in the state’s largest city — would already have a considerably diverse population with a variety of needs in its more than 80 school buildings. But the city is also home to three military installations, giving it even more challenges to consider when it comes to the unique issues those families face.

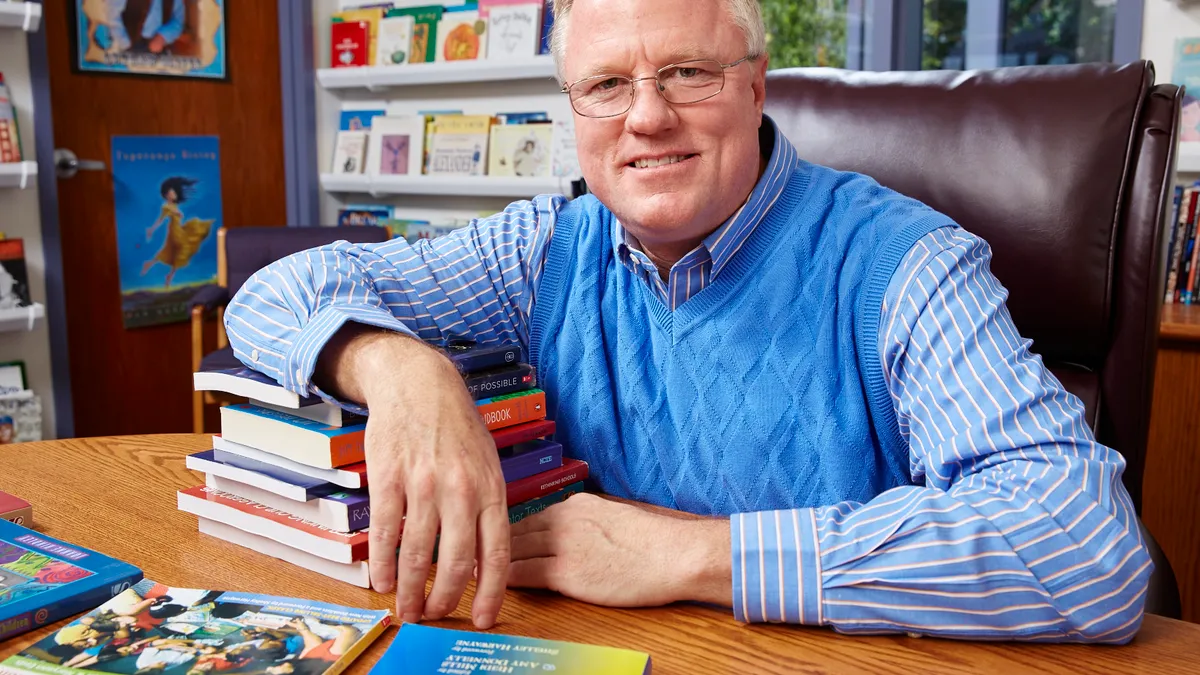

“And then we're kind of a bedroom community for Norfolk Naval Station, which as you probably know, is the largest naval station in the world,” Superintendent Aaron Spence, currently in his ninth year leading the district and 23rd in school administration overall, told K-12 Dive recently.

Over the course of our conversation, Spence — himself a former military kid who attended schools in the district he now leads — shared what the district does to support military families, its strategy for engaging the school community in productive conversations, and the benefits of being a homegrown leader with outside perspective gained through prior administrative stints in Texas and North Carolina.

Editor’s Note: The following interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

K-12 DIVE: I’ve read that one of the things you do really well in Virginia Beach is managing the balance between technical skills and people skills. What would you say is most important to focus on in order to maintain that balance?

AARON SPENCE: I think first it's just understanding the need for that balance, right? That's always been kind of at the core of my belief around what it takes to be great in our work. In our field, if you're an administrator, that means you know how to manage a building. You want to have people who know how to manage their budget, manage their hiring processes, make sure that the lights stay on, make sure that the floors are clean.

But also, the technical skills include being able to, in our field, diagnose instruction. What does good instruction look like? How do you work with students in terms of behavior?

When those things become out of balance, you get some challenges. If you have a high degree of technical competence without great interpersonal skills, things might be getting done, but people are not feeling very good about it, and I don't think that that's a position we can be in in education.

Certainly, if you're just a great interpersonal leader or teacher, you're fun to be around, but if you don't have technical confidence, we're not getting much done or holding ourselves accountable for high expectations. And so you get underachievement.

My position has always been that if we're gonna be great, everybody in the organization has to balance those two things. So we look for that in our hiring, and we look for that in how we coach and evaluate the people we work with.

Given the importance of people skills in the last few years — from communicating things around the pandemic to addressing the variety of controversies and misinformation that have popped up in districts nationwide — what do you think can be done by districts to better communicate to local communities so there’s better understanding of what schools are doing and these controversies are avoided?

SPENCE: What do we do to communicate about all the good stuff that we do, but also how do you do that in an environment where information is out there that's not necessarily true or gets misconstrued?

I would say what we don't do is we don't argue about it. So it's not helpful, I think, to say, “Well, critical race theory isn't really taught in our schools,” because people don't even agree on what that means. And then if you say that, somebody's just gonna say, “Well, you're just not telling the truth. Here are examples,” right?

What we try to do instead is focus on what are the real concerns people have, and how we help talk about what we do in our schools and help alleviate those concerns. One of the things that is really important and I think rings true across all groups of parents and all groups of politically minded folks is we want kids to have a great learning experience. And part of having a great learning experience means they develop a set of skills, both academic and social-emotional, that are needed to be successful in the future.

Another thing that comes up when we talk about interpersonal skills are social-emotional learning skills. And social-emotional learning has somehow become a little bit controversial. But when you take that name away from it, and you talk about the skills themselves — having empathy and being able to manage yourself and being able to advocate for yourself and being able to communicate and work well with others — when you talk about those with parents, parents are like, “Yeah, I want my kid to have those skills.”

And when you look across party lines and across, again, all sets of parents, parents agree — going back to critical race theory — they want our history taught, and they want kids to be able to think about the challenges in American history. But what they also want is to make sure that in the middle of talking about those challenges, we're also talking about the progress we've made as a country and the things that make us great.

So I think it's my job and our job, as we communicate about what we do in our school system, to be clear and confident that those are the things we're actually teaching our kids — that we're not here to indoctrinate children, we're here to make sure children have a great experience, and they're learning the things they ought to learn to be successful when they leave us.

When it comes to serving the local population, what are some of the considerations that come into mind — not just from a diversity perspective, but in line with having a significant local military population?

SPENCE: We're a proud Navy town, and we've been that way since World War II. I mean, I landed here in Virginia Beach because my father was stationed here at Norfolk Naval Station. I would say we have a long history of serving our military community and understanding the special and unique needs of military families. We have continued to adapt to that and the challenges military families and military children experience when they transition into our school system.

And when they transition out of our school system, we are really proactive with that. We have military family life counselors in our buildings who work specifically with military families on those issues around transcripts and scheduling and dealing with issues that military families deal with — things like how kids deal with deployment or death in the family.

We also train all of our counselors on issues associated with our military families as they come in, making sure that they know how to read transcripts from around the country and how we handle those. We're a part of the Interstate Compact on Educational Opportunity for Military Children in Virginia. So we adhere to those guidelines, and we really try to make the processes of moving in and out of our district as seamless as possible for those families.

But also while they're here, we want them to have a great experience. So we have, for example, what we call “anchored for life” clubs. We have those in our elementary schools and middle schools and are starting this year a pilot in our high schools. And those are clubs that are a partnership with the military, with the Navy specifically. What they do is they create essentially student ambassadors who understand and know what the military experience is, who lead specific programs for kids who are coming into our buildings. And then they kind of continue with those programs once they're there, so students who are coming from other places and are being stationed here have somebody they can relate to and talk to as soon as they walk in the door.

We also have military liaisons on our staff who work directly with military families to answer those questions. And then we have a very, very close working relationship with our installations. Each of our installations has what's called a school liaison officer attached to it, and our military liaisons and military counselors work very closely with our school liaison officers to make sure families who are coming in with specific challenges or questions get those answered.

Given the known benefits of having a homegrown administrator, what do you feel are the advantages of you having not just that homegrown perspective, but of also having served as an administrator in districts across the country and then bringing that experience back to your hometown?

SPENCE: I really think it's a unique opportunity to come into a place with an insider's perspective and an outsider's eyes. To really know the positive things and to have the positive feelings and the positive experience that comes along with having come through the school system and had a great experience and knowing what we can do for kids, but also coming in and being able to kind of look around … sometimes when you've been in a place for a while, you begin to accept your reality as sort of, “This is how it is.” If you come into a place from outside, you can look around and say, “Well, I see it a little bit differently.”

I feel strongly that our staff understands how much I appreciate the organization and the culture of the organization, and have tried to nurture that culture and grow that culture while at the same time looking around and saying, “How can we continue to get better?”