Lessons In Leadership is an ongoing series in which K-12 principals and superintendents share their best practices and challenges overcome. For more installments, click here.

If you were asked to name a location where schools were being particularly innovative, a mill town in North Carolina might not be the first place that would come to mind. But at a time when many districts nationwide stumbled on tech rollouts, the Rowan-Salisbury School System gained a reputation for getting the formula right.

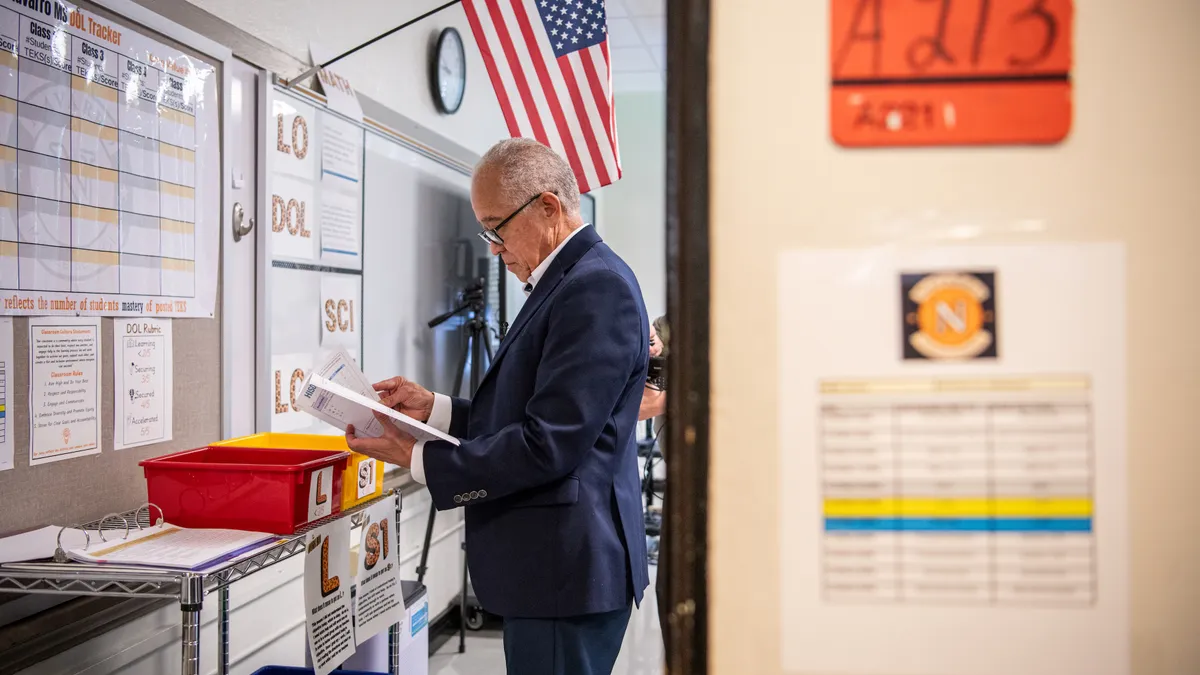

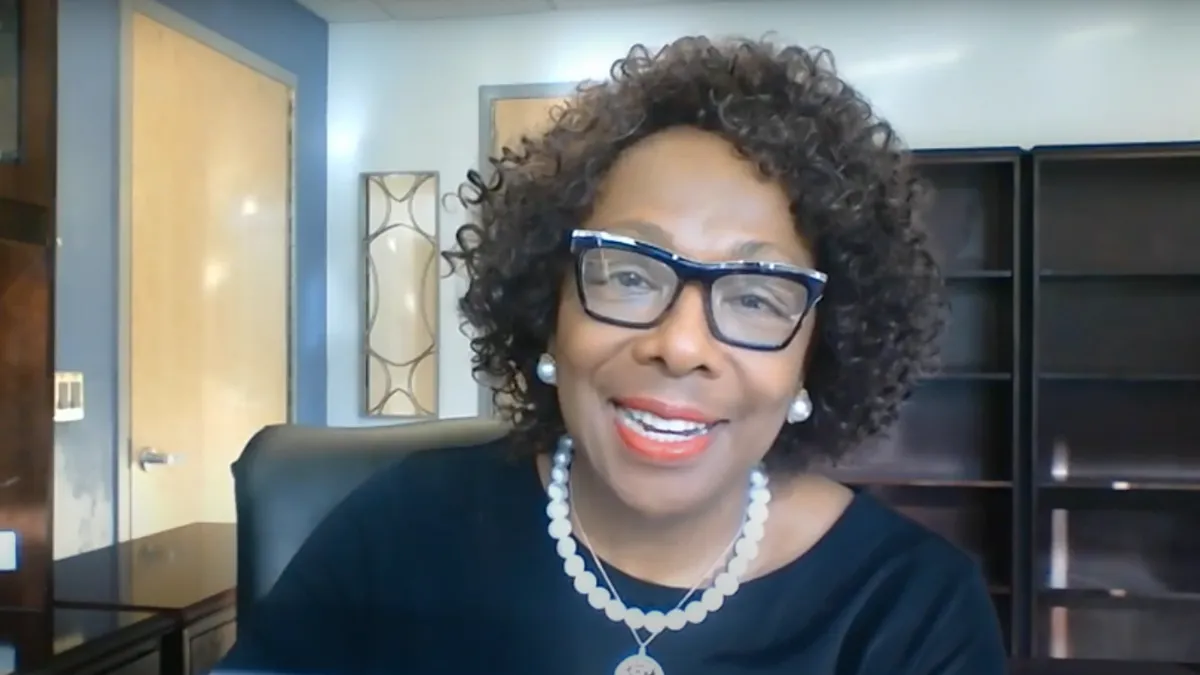

In this Q&A, Superintendent Lynn Moody, who has led districts across the Carolinas for 15 years, discusses how technology and innovation fuel a focus on helping students discover their passions, and what's top of mind for the district as it moves forward.

Editor's Note: The following interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

EDUCATION DIVE: One of the things that's always stuck out to me about Rowan-Salisbury is its track record for innovation, and it attained that at a time where other districts fumbled a bit on their tech rollouts.

LYNN MOODY: Right. When I was a superintendent in Rock Hill, South Carolina, I had met Mark Edwards, who was the national Superintendent of the Year at the time. He was in Mooresville, North Carolina, and they were doing remarkable things. I was really impressed by that journey and wanted to learn more about it and tried to learn all that I could.

We began a digital conversion in Rock Hill prior to me coming here. At the time, I thought it was about the digital conversion, not really realizing that was just a tool. I've come a long way with my thinking, but in the beginning [of districts going digital], it was really just trying to find any models that you could learn from.

I remember when I was interviewing [in 2013] with the board [in Rowan-Salisbury], I said, “I love innovation. I love creativity. That's my game. If you want things to stay the same, hire a different superintendent. I like transformation, and I'm excited by that. If that's what you want, I'll be the person you should hire.”

So we started on those grounds. I knew that a digital conversion would be part of what I thought would be important toward the change process, but I came with a little history. I'd already cut my teeth, so to speak, on a digital conversion in Rock Hill.

I knew some of the downfalls and some of the things we needed to do inside the community. But I also think Rowan County was in a place where we had been a low-performing school district for a long period of time and in a really tough economy here.

We are very much a mill town and [the mill closed]. So like a lot of rural North Carolina, we are just really struggling to find our way. [Transformation] wasn't really that difficult of a sell because they wanted some change. They were already looking for some hope things would be different. Sometimes, I think this work is more difficult in an affluent school district that's doing really well. Your “why change” becomes more difficult to sell. Here, the community embraced looking at something new.

Given the economic situation, how much more important does career and technical education become in your community?

MOODY: It's extremely important in our community. The digital conversion put me in a place to be able to talk about our innovation and creativity and our work and what we were trying to do with students around some of the right people in our general assembly. And 20 months ago, I convinced our general assembly to allow us to become a renewal school district.

A senator and a representative crafted legislation — that's House Bill 97 — that allowed us to become a renewal district, which meant we have all the flexibilities of charter schools. This is a huge trust for the general assembly … [to say] we were doing innovation and to give us the freedom to try to break all the rules, so to speak, to create a different kind of school district that would serve our children better.

As we've gone down that journey, we've learned lots of lessons. We've found it's not just about innovation, it's really about rethinking everything differently. When we look at models of education across the country that are rethinking education, with many models that have done a good job of that, their goal being for all of their students to be college-bound, and in our community it is really important.

[Our focus is] on helping our children find something they believe in, that they're excited about, that they're interested in, and using that passion to accelerate their learning across the board. We think that the jobs they will go into and what they create in the future are very different than what we have, and we don't want to limit their scope or thinking about what the job potentials are now to what they could eventually be.

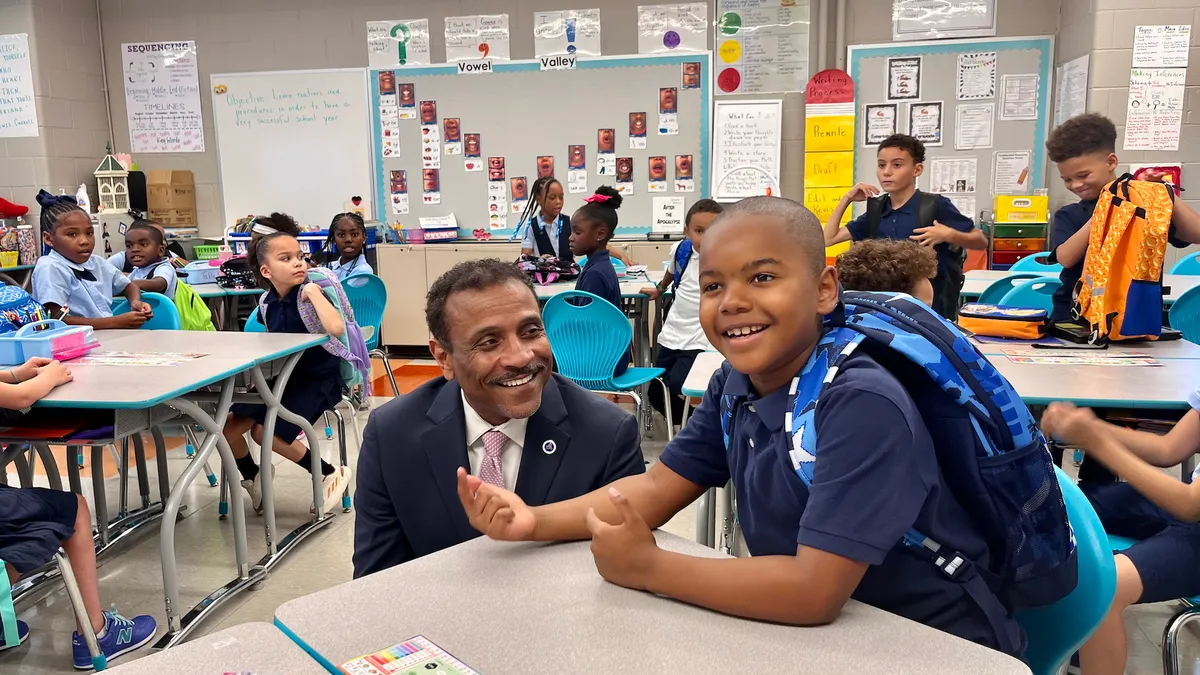

I read to a group of 3rd graders at one of our schools about vision and dreams and climbing, and asked, “What is your vision? If you could solve any world problem, what would you do?” Of course, sometimes they'll group think in elementary school, so one will say something, and they'll all kind of jump in.

But six young boys in that classroom all said, “I want to be in the military. I want to solve problems in the military.” The military is really important in our community. It's talked about a lot. It's an honored profession. Career and technical education is an honored profession, and [so is] going to college.

Our goals around renewal and what we want to be accountable for to our community are, when we think of our students as gifts to our community, the gift we want to give back ... is our students prepared to either be enlisted, enrolled or employees.

An example with that 3rd grade group of young boys I was talking to about vision: We talked about what are the things about the military you like, and one said, “What I really like about the military is they wear really cool uniforms.” I said, “They do wear really cool uniforms. Would you be at all interested in helping design that uniform to look different, to make it even cooler or to make it so it could sustain heat or problems they might have in the field when they are trying to protect the country?”

We don't want to just teach them to get ready for a test. We want to teach them to explore how they feel about things. What are they thinking about? What great problems do they want to solve in the future? How will that passion make them resilient in their learning?

We believe that equally important are those interpersonal skills. We said the academic skills will get you the job, the interpersonal skills help you keep the job. So how do we help our students develop and reflect in those areas around work ethic and leadership and civility? We believe all those things are important to a strong education.

When it comes to the innovative efforts in the district and allowing students to demonstrate passions, what's top of mind right now?

MOODY: It all kind of plays together. We are in the middle of asking for a technology refresh, so we have to have this conversation with our community all over again: Why did we believe digital technology was an important tool for our students? Why did we choose the tools we chose? What were we hoping to accomplish? How does this accelerate their learning in any way?

One of the things we are working very hard on is a new digital portfolio for our students. When we talk about passion, where they can record in their portfolio who they are, what makes them a special learner, how do they learn best, what are their learning styles, what are the things they’re passionate about, and what are some evidences of their work that will ultimately build over time.

Upon graduation, we would be able to give those students going on to colleges and universities a different kind of transcript that really defines them as a learner. We know in talking with colleges and universities, for example, they’d much rather have a student who actually created a solar farm and took three AP science classes but maybe made a C in English than somebody who's at the top of their class and went on a mission trip but never did anything in the science field and don't really have any evidence of work or passion. They know student A is going to far outperform student B, but they don't have a way to measure and judge that yet. One of our projects is to work on that, to think about what kind of transcripts [we’re providing].

Likewise, a student would be able to present that to an employer or someone who might be interested in investing in the new business that they're trying to create so they have evidence of this work and their passion. That's really hard to separate. That would be terribly difficult to do on paper and pencil. It would just require different kinds of tools, plus with many of the areas that our students are passionate about, we don't have those jobs in our community. So they have to, for example, use the tech to Skype with somebody somewhere else to be able to learn.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards