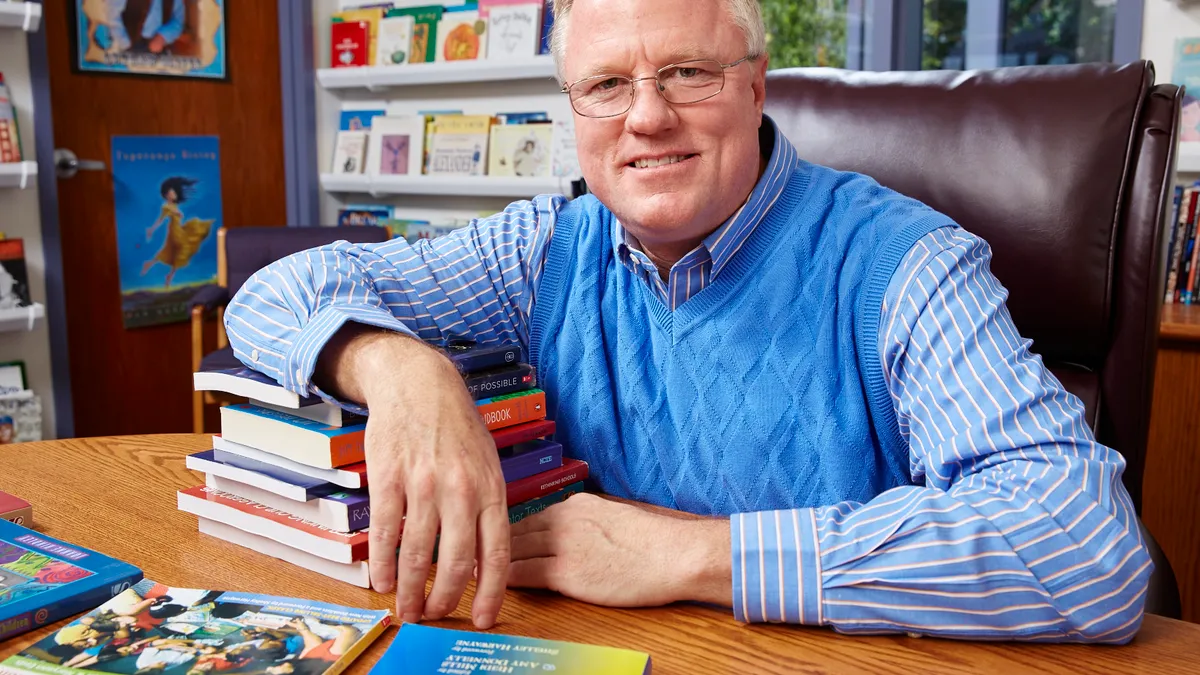

Lessons In Leadership is an ongoing series in which K-12 principals and superintendents share their best practices and challenges overcome. For more installments, click here.

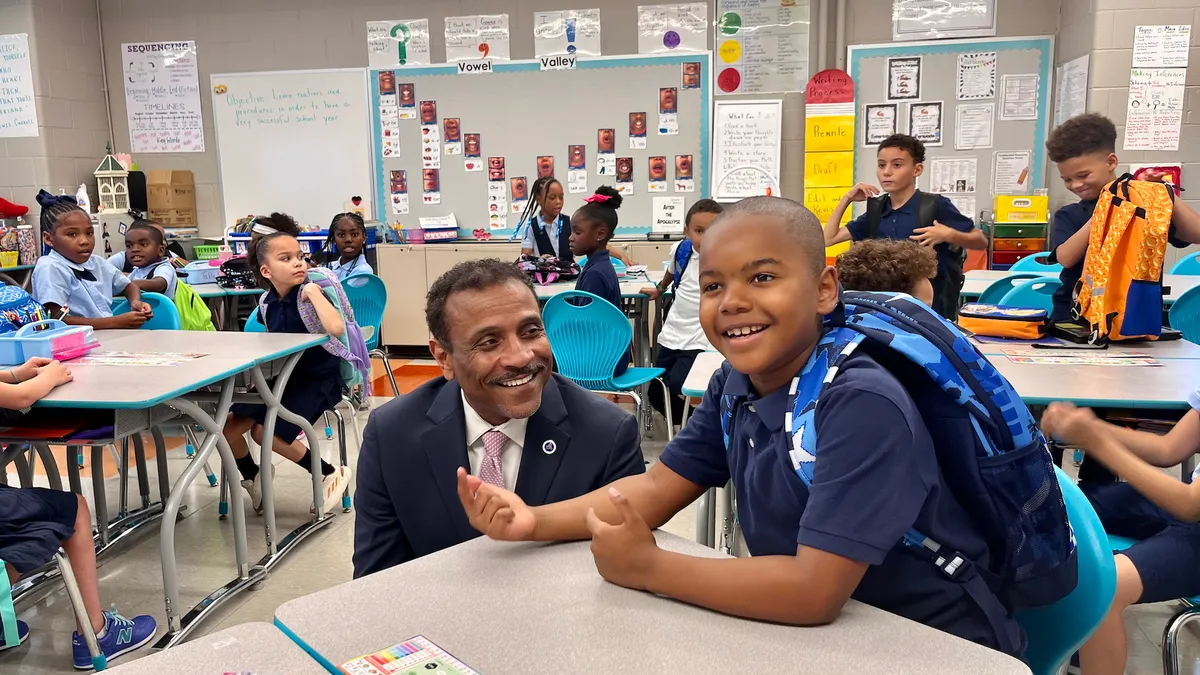

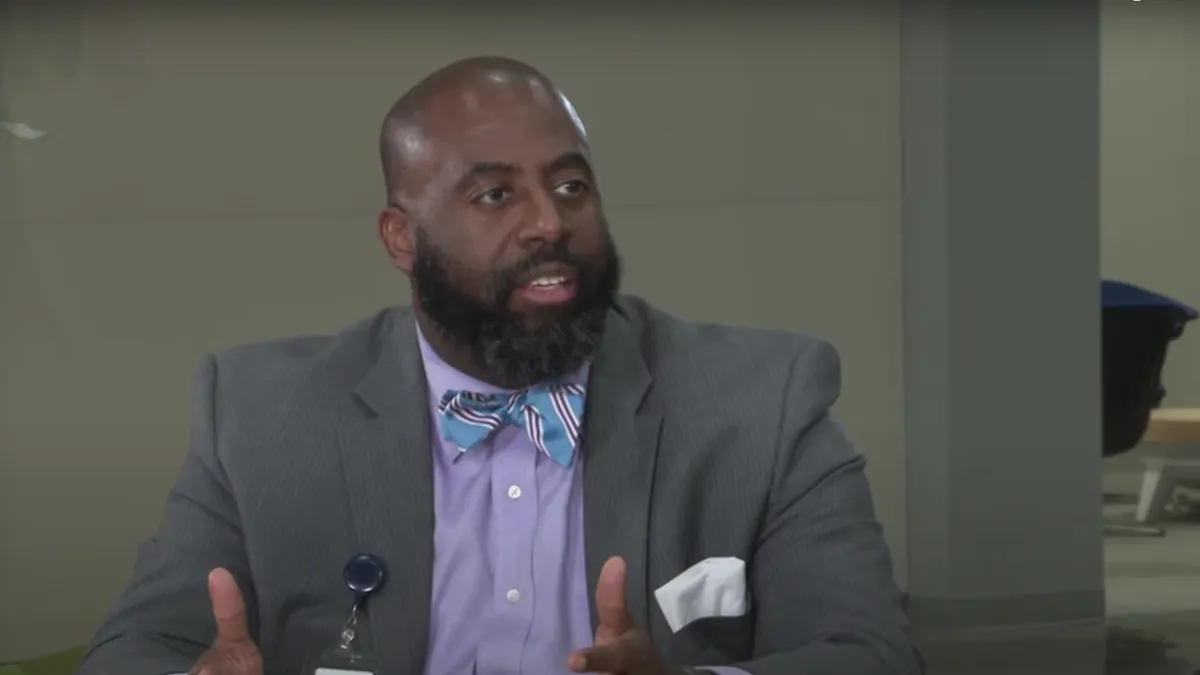

Leading a school with a high population of underserved students in one of the nation's poorest cities is difficult enough in normal times, let alone in the midst of a pandemic and a period of high civil unrest. But it's a task Richard Gordon, principal of Paul Robeson High School in Philadelphia, is continuing to perform to great success.

No stranger to accolades, the 2017 Education Dive: K-12 Administrator of the Year recently was recognized as a Diversity MBA Top 100 Under 50 for 2020, the Pennsylvania Principals Association's 2020 Pennsylvania Principal of the Year Award, and the National Association of Secondary School Principals' (NASSP) Distinguished Service Award for Service to Education. He is also a finalist for NASSP's National Principal of the Year for 2021.

He gives the credit for these accolades, however, to the community (he's added over 30 new partnership s during his tenure as principal) and his team.

"You cannot, especially in these times we're currently in, underestimate the power of community partnerships and collaborations. They have made a significant difference in our school," Gordon said, later adding that his team of teachers are "award-winners in different ways, and they continue to drive results here in our building."

We recently caught up with him to discuss how his focus on equity prior to and throughout COVID-19 and ongoing demonstrations, as well as further supports planned through community partnerships.

EDUCATION DIVE: Something that's obviously had a huge impact on equity over the last few months is the pandemic and shutdowns. How has that impacted your school and students and the way you’re able to serve them?

RICHARD GORDON: We’ve always prided ourselves in making sure we meet the individual needs of our students. The challenge for us was just making sure students had access to laptops, that they had access to internet and had access to the teachers as frequently as possible. Those were our top priorities. Then, making sure that there was an open line of communication, making sure the students knew it was going to be a two-way line of communication where we want them to check in with us.

Certainly, we had a regular process in place to ensure we checked in with them and their families, as well, because probably the biggest challenge through this transition was really more about two things. One, the students feeling that sense of isolation. The two-way communication was a means of breaking that down and letting the kids know we're still here, we still care for them, and we still want them to feel connected to the school — not just as individuals, but also as a group, whether it's by grade or by school as a whole. The second issue was really understanding that through this whole process, our students are still dealing with a lot of competing issues.

Even on a regular day, school might be second, third or fourth on their list. Now you throw in the pandemic, and you kind of exacerbate those issues even further. So we wanted to make sure we also offered a sense of flexibility and offer that connection to lets kids know we understand. We’re very empathetic about situations many of our kids are facing, and we wanted to make sure we provided them every opportunity for support through this whole process so they knew no matter what they were going through, they were going to be able to be successful because they want to collaborate with us in order to get over those humps.

Your school has a large population of Black and brown students, and Black and brown families were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic and a lot of the challenges it's presented. What are some of the resources and supports your school is planning heading into the new academic year?

GORDON: Interesting enough, I just had a meeting with the University of Pennsylvania. ... [It] has an outreach office called the Netter Center, [which] has outreach in the community and particularly West Philadelphia.

So I asked the Netter Center to start taking a look at not just how the outreach or programs can be offered to schools, but also what other programs can we begin to offer our families, because one of the biggest challenges of the pandemic has been unemployment and the instability of employment.

The question is, “Why can't we start to collaborate together as some type of West Philadelphia consortium to take a look at what types of family supports and employment opportunities we can provide some of our families?” We definitely look at unemployment. We definitely look at mental health issues.

We're also collaborating with the district attorney's office, which is developing resource hubs around the city. We want to make sure we’re part of that conversation, as well.

We just want to holistically be able to address not just the kids, [but] the stress students feel when their families are going through so many concerns. And we have to start making sure we reach out and deal with those family issues, as well.

Another source of potential stress has been the demonstrations around the Black Lives Matter movement in response to the police-involved deaths of Black Americans. How are you navigating the line between providing support for students who want to be engaged and also the potential risks to them based on what we've seen during the demonstrations?

GORDON: What's interesting about the times we're in is I feel like I'm one of the actors in Casablanca, where they're like, “Oh my God, there's gambling in here.” It's like we're suddenly waking up to the idea that racial discrimination has taken place in our city, in our country, and it's hitting us regardless of what side of the political aisle you find yourself to be on.

I've always had those conversations with my school population, and something I've always been addressing with our teachers, as well. There are formal supports coming out of headquarters, where they're asking us to do different versions of social-emotional learning, and those things are great. But there's really nothing surprising here as far as Robeson High School is concerned because we always knew that was an issue.

Let me give you an example. The conversation I often have with our students is looking at the bigger picture, because we understand there’s police brutality and killing of unarmed Black Americans in this country. However, in the larger picture, that's still a smaller percentage of the bigger picture that's out there, that's happening with us. And at the end of the day, with the systematic racial discrimination that takes place in our cities and in our country, the policing piece is a byproduct of that.

And it comes out of nowhere. We just saw this with Masai Ujiri from the Toronto Raptors, where even as a millionaire, he still had a very negative interaction with the police. Whenever we have those conversations about negative interactions with people, whether it's police, our bosses or just individuals at a store, our story is never believed until it's on camera to prove it.

Black and brown Americans are starting to feel very boxed in, like what do you want us to do? You still want us to accept those situations and not act out or not protest or not say anything or not make a big wave. So you’re damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

These are the conversations we have at Robeson every day. At the end of the day, the big picture is: We have all of these obstacles in our way, and we still have to overcome them to try and push forward to succeed. Therefore, the supports we’re providing our students are the same supports I've been providing to them since I arrived at this location.

I have lived these experiences, and I feel as though as an African American male and now in a position of authority as a principal, it is my obligation to support our students by having these conversations on a day-to-day basis. We're not doing it just in the last six months because it's popular in the country.

I grew up in poverty in Camden, New Jersey, and now I'm working in an impoverished city, Philadelphia, where the poverty rate is 24%. We are the poorest big city in America. The experiences our kids see every day are the experiences I grew up and lived with. I try to use my personal experiences to truly kind of guide and help explain to our students that life isn’t fair and fair is not equal and equal is not fair.

Despite all that, life doesn't stop. Life moves forward. So we have to continue to move forward and figure out the best pathway to move so we can create the best life for ourselves, despite our circumstances.

I want to begin the process of motivating our kids to want to dig their way out of poverty while at the same time we finally take on the systems that are enhancing and continuing the poverty rates happening here in Philadelphia and cities like Philadelphia across the country.