To David Trowbridge, one way to make sure curriculum is relevant for all students is to take a look in a school’s own backyard. As director of African and African-American Studies at Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia, Trowbridge believes local history is a great way to pull students right into a historic moment, particularly when it comes to teaching about African American history across the United States.

It’s also a method he’s championed since launching Clio, an online site and free app that takes people on historic walking tours in their local area. His favorite entry on the app is the location of a sit-in that occurred in his hometown.

“There is no physical marker, but the digital marker we created includes digitized newsreel footage of the sit-in along with links to related primary and secondary sources," he said. "It feels almost like a time machine when you see the sit-in happen right in front of you where you are standing and can learn about the people and context.”

With African American History Month kicking off in February, educators should ensure the curriculum is both relevant to and inclusive of students. This could mean highlighting local sites rich in historical significance, including historic figures who, in their time, would have been the same age as the students being taught today, and even having teachers reexamine the resources they’ve used in the past to dig deeper for new material.

Get into the details

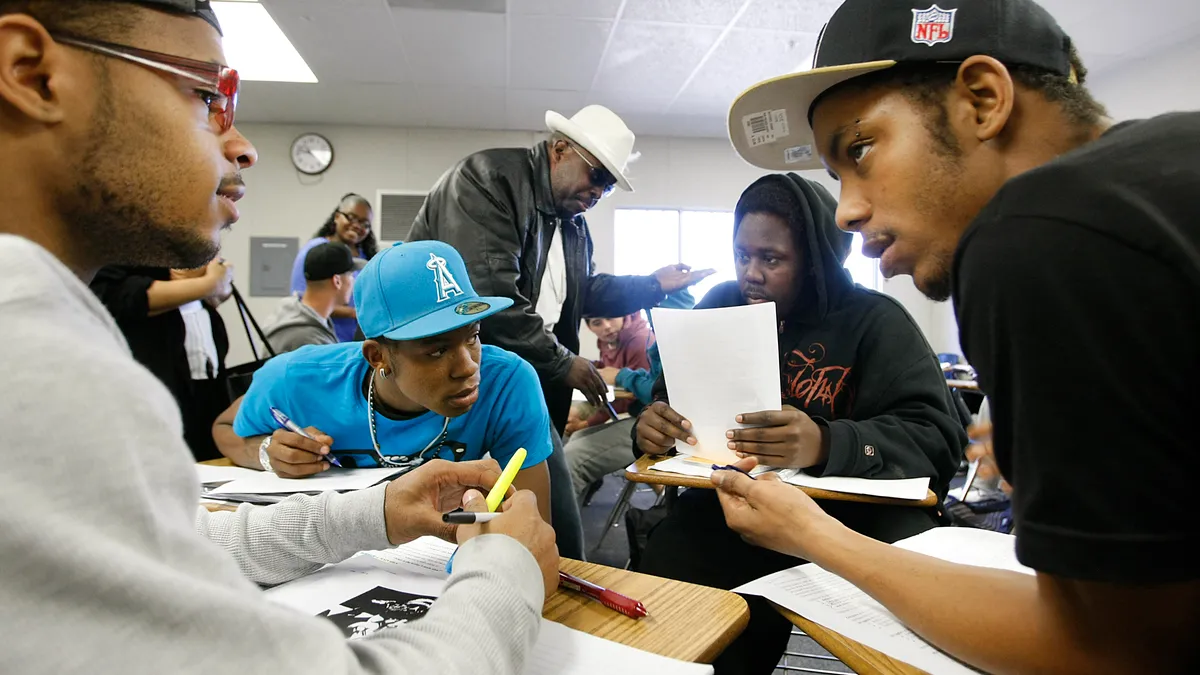

One way to get educators and students out of autopilot in their learning is to engage students in their own research, uncovering their own data and details to help support the themes and learning happening in the classroom.

“If they don’t get into the research, students won’t get out of automatic default mode,” Trowbridge said.

His walking tours, for example, help young people step away from books and make the history they’re studying come alive, potentially engaging students far more than a lecture ever can. On the subject of the Civil Rights Movement, there are currently 55 entries, according to a recent search on Clio, that can be tapped by educators from anywhere in the country.

“There’s something about seeing the immediacy of the civil rights movement right from where they’re standing,” he said.

That said, he also favors turning to original, historic resources — as long as they’re complete and well-sourced. Trowbridge said too often educators turn to quotes and materials that can be pulled out of context, or decide to highlight people in their lessons who are already well-known rather than investigating others who have played significant roles in history but aren’t cited as often.

For example, one person he likes to include when teaching about the civil rights movement is Ella Baker, who was integral to the founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, also known as SNCC, and played an important role in organizing the sit-ins in 1960.

“People say she was behind the scenes,” he said. “Yes, but a movement cannot be one person.”

Question biases

Julie Holcomb, an associate professor in the Museum Studies program at Baylor University in Waco, Texas, thinks teachers should also question their own biases and ensure what they’re including in classroom materials reflects the community where they and their school are located. Holcomb teaches students to question what’s included in museum exhibits, for example.

“Museums have a history of being seen as temples of learning and not very friendly and approachable,” she said. “We’re looking at how can we make our museums more accessible to a broader population, and wherever that’s true, make more inclusive exhibits.”

For teachers eager to bring that same approach to their classroom — and their curriculum — Holcomb suggests looking online for resources to widen the voices brought in to their lessons. She points to the American Association for State and Local History and the National Council on Public History resource "The Inclusive Historians Handbook" as a good place to start, where there are details on how to define and work with concepts from civic engagement to urban renewal.

Include student voices

John A. Kirk, the Donaghey Distinguished Professor of History at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, encourages educators to include as wide an array of voices and representation as possible in the curriculum they’re developing to help make lessons more relevant to students.

He suggests educators bring in examples of young adult historical figures — from the four college students who were the first to participate in the 1960 sit-ins at a Woolworth lunch counter in North Carolina to the students suspended from school in 1965 for wearing black arm bands in protest of the Vietnam War — who contributed to pivotal movements. Showing students how people their own age made political impact may help to engage them and connect students to history, Kirk explained.

Primary sources are a good way to find these individuals and can also help educators bridge the time gap to bring the significance of a historic moment back to students. And turning to figures who may not be as well known to children and teachers alike can help to enliven the history as well.

For those teaching about the Civil Rights Movement, for example, Kirk points specifically to Ruby Bridges, who, in the 1st grade, was the first African American child to attend William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans, escorted to school daily by federal marshals. Educators can reference Bridges’ own 1999 book, “Through My Eyes."

The book can be found through the Zinn Education Project, which Kirk recommends as a resource for teaching materials educators can use, as well as primary sources in many different mediums from print to video.

“It is important to explore, expand and bring in different perspectives,” he said. “Anything that connects to a learner is a good way to get them to understand.”