The district: The Compton Unified School District in California is located near Los Angeles and serves nearly 26,000 students. Students classified as Hispanic comprised 81.9% of the student body, and students identifying as Black were 16.9% of the student population, according to 2017 data from the U.S. Civil Rights Data Collection. More than 85% of students received free or reduced-price lunches.

The district’s graduation rate has been improving and was 87.1% in 2019, up 3.6% from the year before, according to state data.

The challenge: CUSD wanted to strengthen efforts to recruit, retain and promote male African American, Latino and Asian teachers who serve as effective and positive role models.

Nationally, public school teachers are overwhelmingly female and white. Only 24% of public school teachers were male in 2017–18, with fewer male teachers at the elementary school level (11%) than at the secondary school level (36%), according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics. Teachers who classify as a race other than white, or as two or more races, make up only about 21% of the public elementary and secondary school teachers nationally, NCES data shows.

At CUSD schools, there was a desire to help male teachers of color build their skills and confidence in vying for leadership positions. Too often, male teachers of color only see themselves, or others see them, as father figures or disciplinarians but not curriculum or fiscal experts, mentors to other teachers or instructional directors, said Travis Bristol, assistant professor at the University of California, Berkeley's Graduate School of Education, who helped create the Compton Male Teachers of Color Network in 2018.

The approach: Bristol worked with John Reveles, an elementary education professor at California State University, Northridge, to form CMTCN, which was supported by a three-year $250,000 grant from the FEDCO Charitable Foundation, according to Cal State, Northridge. Bristol approached Blain Watson, a Compton Unified principal he knew who was leading Dominguez High School at the time.

“I, myself, as an educator of color, man of color, I immediately saw the value in this,” Watson said. “I know from my own personal experience, and just the stories of the men in this group, that they were looking for the opportunity, the space, that shoulder tap to step into a position of leadership,” Watson said.

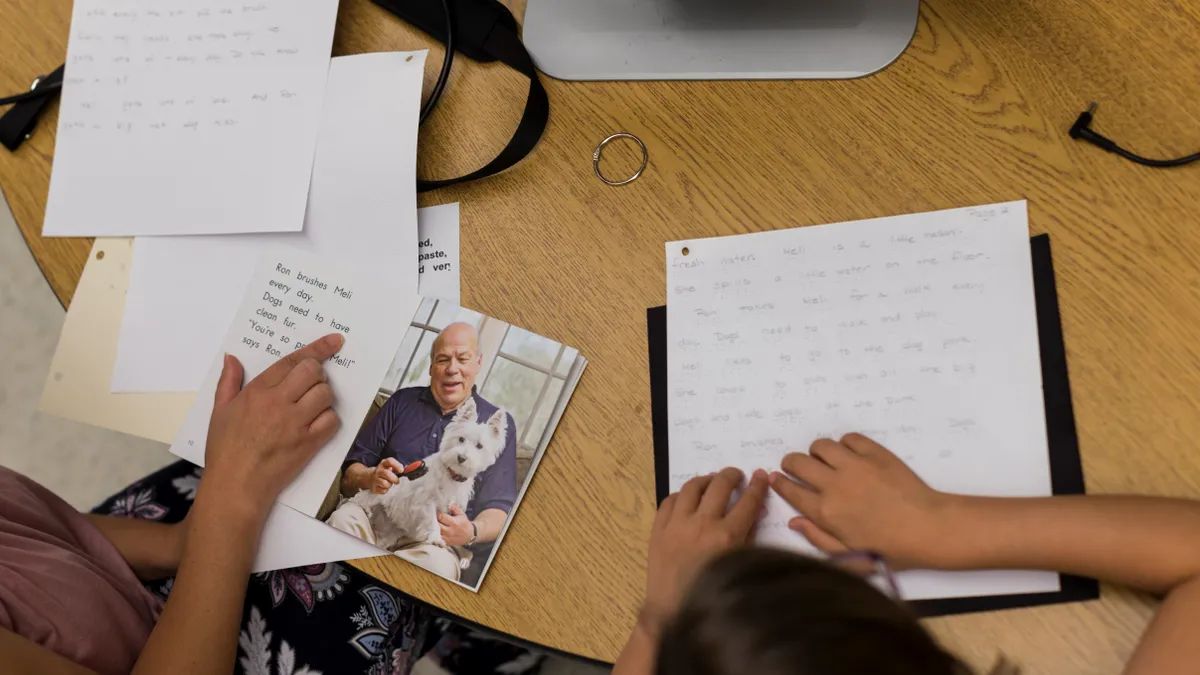

With the district’s blessing, the organizers recruited one other administrator in addition to Watson and eight teachers to be in the first-year cohort. The group of teachers and administrators, who were paid a stipend to participate, would meet on Saturdays at least once every other month for six hours, with the agenda focused on in-depth discussions about real-life professional challenges the educators and administrators were having in their practices.

Much time was dedicated to understanding the challenges, reviewing approaches that had been tried, and brainstorming other potential solutions. The group also discussed their social, emotional and physical health and well-being; traits of effective leaders and mentors; and how being a person of color influences experiences in the classroom and school building.

At the end of the first year, the group invited the school community to a showcase where they shared what they were learning and the personal growth they were making. Students also spoke during the showcase about how they valued having teachers and administrators of color who are role models, said Watson.

In the second and third years of the group’s existence, participation in the network has grown to 22 teachers in the high school and in its elementary and middle feeder schools, said Watson.

What worked: Building a level of trust among the group when it first started meeting was essential to preparing for honest and sometimes critical conversations about a teacher’s or administrator’s approaches, said Watson and Bristol.

One of the unique features of the network is that administrators are learning alongside teachers as equals, willing to take criticism and suggestions, Bristol said. He said he created the joint administrator-teacher professional development program because one of the biggest reasons teachers leave their jobs is because of poor school leadership and negative work environments.

“This idea that, in schools, right now, teachers learn by themselves and principals are by themselves,” Bristol said. “But, you know ... in order to have a coherent sense of moving a school forward, an organization forward, you have to have teachers and principals that are learning alongside each other so that they can understand how each other might be seeing the problems and the solutions that have to happen together.”

Watson said the group made him learn to be more vulnerable as a leader, which allowed him to have a more authentic leadership approach and be more flexible to different ideas and situations. Knowing he had a growing community of support made him a stronger leader, he said.

“I learned a lot more about the school's culture, and a lot more about its institutional history,” Watson said. “I learned a lot more about the disposition I needed to adopt in order to best lead the school. I learned about different relationships that needed to be supported differently. These guys will give me the insight I need to be successful.”

Brandon Contreras, an 8th grade math teacher who joined the network during the 2019-20 school year, said the professional exchange between teachers and administrators in the group helped build his confidence and drive as an educator.

“When you have a principal who's speaking like that to teachers, and it sounds like everybody is equal and has equal say, and can make a contribution that is going to be valued, it's really empowering for everybody,” Contreras said.

Areas of adjustment: The pandemic forced the group to meet online, instead of in person. Although the group uses video conferencing to examine real challenges and discuss best ways to lead and mentor, it is not ideal and everyone misses the face-to-face meetups, Contreras said.

“We still talk, laugh and listen,” Contreras said. “The work is still happening and the connections are still being made.”

This is the last year of the three-year grant, and the group is seeking additional funding to keep the effort going and expand its reach even beyond CUSD. New funding would help pay for stipends for the participants, plus curriculum materials and breakfasts and lunches when the group is able to meet in-person again, said Watson.

Lastly, Watson remains involved in CMTCN but left the school district last year. Contreras has stepped in to help lead the group’s meetings and plan the agendas.

The results: The network has expanded its membership and reached into more schools in Compton Unified, furthering its mission to help support male teachers of color. According to Reveles, the retention rate of new male teachers of color at Compton in the 2019-20 school year was 98%. Additionally, 16 of the 17 teachers who serve as mentors to other teachers in CMTCN are still teaching at CUSD this school year, Reveles said.

“The school district now has a larger cadre of men of color, serving as mentors, serving as expert practitioners in the district, people that can be turned to to help novice teachers,” Bristol said. ”That’s really transformational that we're changing the makeup of the mentors in the district.”

Watson said the network’s teachers have taken leadership roles since the time the network began. For example, teachers have joined school advisory councils, become club advisors and led professional development programs for teachers of English learners and technology. Two teachers have also started working toward their credentials as administrators, Watson said.

“I think this will increase people's believability in the capacity of male educators of color, and really support, in many ways, a paradigm shift and how we organize the infrastructure of our school, and how ultimately, the administrator, principal or assistant principal distributes his or her leadership,” Watson said.