Editor's note: This story is the first in a series of pieces that will examine the impact of a number of health and social issues on education planning, funding and operations.

When a star football player who had recently graduated from Spring Mills High School in Martinsburg, WV was found dead after taking "bad opioids" last month, his former teacher, Jessica Salfia, penned a Facebook note begging the public not to see him as just another statistic in a state that has come to be associated with drug overdoses.

Instead, she wanted the world to know Jorge Armando Mercado-Medrano was a guy who "hated failure, who was always optimistic and believed in his team's ability to win, who smiled every Friday at me as he walked by my door and asked if I was coming to his game, who should be remembered as someone who was smart, creative, funny and kind."

But unfortunately, despite Salfia's pleas, in many places, such occurrences are becoming the "new normal."

A recent report by researchers at Penn State University found heroin and prescription painkiller abuse on the rise, thanks to wider availability of both forms of the drugs. Across the U.S., 28,647 deaths, or 61% of all drug overdose deaths, were linked to opioid use in 2014. Since 2000, the Center for Disease Control reports the opioid overdose rate has tripled, while deaths from heroin overdose have quadrupled over the past decade.

The epidemic's effects have sent shock waves through American society, and schools and universities have been no exception. The increased demand on already taxed districts and colleges to provide increased counseling services, as well as gird up against the possibility of such incidents is yet another challenge in the education landscape. The National Institute on Drug Abuse says one in 12 high school seniors reported having tried Vicodin for recreational use. One in 20 reported abusing OxyContin. And for college aged students, one in 10 reported having a prescription for OxyContin or Vicodin, but 20.2% said they took more than they were supposed to.

Key Facts: National opioid use

- 21.5 million Americans aged 12 and up had a substance abuse problem in 2014. 1.9 million of those were to prescription pain meds, and 586,000 to heroin.

- Approximately 23% of heroin users develop opioid addiction.

- Drug overdose is the number one cause of accidental deaths nationwide, and opioid overdoses are tops. Of the 47,055 lethal drug overdoses in 2014, 18,893 were attributed to prescription pain meds, and 10,574 to heroin.

- 80% of new heroin users got their start on prescription painkillers.

The 41st annual Monitoring the Future report, conducted by a team of researchers from the University of Michigan and sponsored by the National Institute on Drug Abuse found 5.4% of teens used narcotics other than heroin in the past year. Those might include morphine, Oxycontin, Vicodin or Codeine, all of which are addictive opioids. Those drugs are a proven gateway to heroin. Half of heroin users report they began by using painkillers. Most cite cost as their motive for switching over to heroin, since the street drug costs about one-tenth as much as prescription painkillers.

"Our young people are dying from overdoses related to opioid use," said Beth Mattey, the President of the National Association of School Nurses (NASN). "Narcotics when not used as prescribed can be addicting. Once a user has difficulty finding prescription narcotic pills, the cheaper alternative is heroin."

Mattey believes it's important for school districts to recognize the epidemic of prescription drug abuse as a first step towards thinking about prevention and treatment.

"Addiction is a disease, and we need to recognize it as a disease," Mattey said, noting it can be difficult to get adolescents into treatment.

A 2013 survey from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found that while young people perceive heroin to be the most dangerous drug, the number of 12-17 year olds who see the drug as "very risky" is on the decline.

Key Facts: Behavior in youth (12-17)

- In 2014, 467,000 teens aged 12-17 reported using prescription pain meds, with 168,000 being addicted.

- In 2014, an estimated 28,000 12-17-year-olds had used heroin in the past year, and an estimated 16,000 were current heroin users. An estimated additional 18,000 had a heroin use disorder.

- People often share their unused pain relievers, unaware of the dangers of nonmedical opioid use. Most adolescents who misuse prescription pain relievers are given them for free by a friend or relative.

- The prescribing rates for prescription painkillers to patients in this age group nearly doubled from 1994 to 2007.

However, Monitoring the Future found the use of MDMA, heroin, opioid painkillers and amphetamines nationwide all declined for 8th, 10th and 12th graders in 2015. And the rate of heroin use has fallen by more than half for 10th and 12th graders since the year 2000, and has fallen 66% for 8th graders since 2008.

But in some pockets of the country, opioid use is increasing dramatically.

Increased Pressure on Schools

New England, in particular, has been ravaged. In Vermont, the State Health Department reported an increase of 40% related to the treatment of opioid addicts in 2015. In New Hampshire, drug overdose death rates have increased rapidly, spiking 69% between 2013 and 2014.

Over the last year, two students, one 15 and one 19, who attended New Hampshire's Berlin Public Schools overdosed. Both survived. The high school has a heroin usage rate that is reportedly 93% higher than the average for the state's other schools.

Berlin superintendent Corinne Cascadden told Education Dive districts need to realize that helping students deal with drug and alcohol issues isn't the responsibility of public schools alone. It takes a multi-faceted approach.

"To successfully support students, collaborative partnerships must be actively engaged in alternative means of treatment and maintaining recovery for students," Cascadden said. "For years, we have taught prevention skills and will continue to do so, but for a percentage of students, more structured programming and supports must be implemented."

In her time as superintendent, Cascadden says she's seen "tremendous stress" on schools to provide "more and more social and emotional services, from adding dental services, afterschool programs, fruit and vegetable snacks and school-based mental health."

"There must be strong partnerships with local agencies to assist in raising the whole child," Cascadden explained. "We are seeing students in elementary grades who were either born drug-addicted, or have substance abuse [issues] in the home. These students need many services before they can be ready to learn."

Next fall, Cascadden's district will begin a pilot program that involves home visits by school personnel into students' homes, in order to better engage parents in their children's education.

Mattey recommends school systems seek outside resources, like the government-run Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) website. She also recommends that K-12 schools embrace a program called Smart Moves, Smart Choices to help inform students about the dangers of prescription drug abuse.

The Smart Moves, Smart Choices website offers free downloadable toolkits for middle and high schools to use, as well as resources for younger learners.

"There is now a component for elementary children as well," Mattey said. "It helps children understand the importance of taking medication as prescribed and only from a trusted adult."

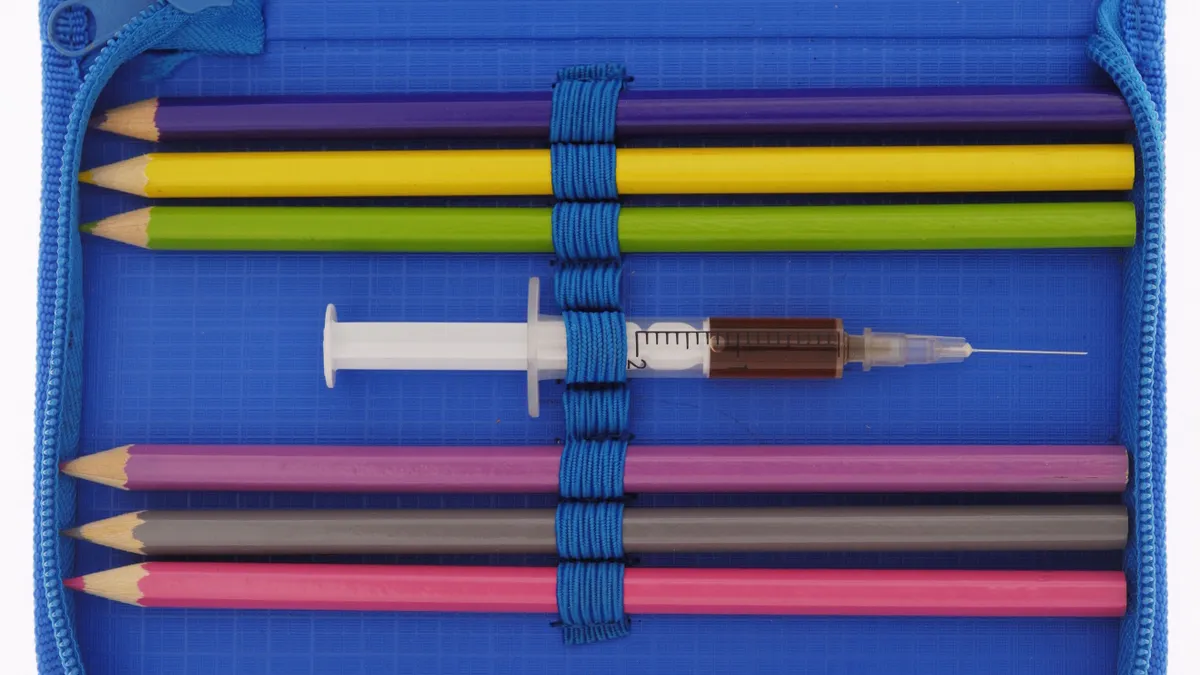

School-stocked antidote

Berlin is the fifth district in New Hampshire to keep Naloxone, an opioid overdose-reversing counter-drug, on hand. Administered as a nasal spray, the drug's manufacturers are partnering with the National Association of School Nurses to provide funding "to increase awareness of opioid-related risks among students, educators, families and communities." One case of the nasal spray will also be made available for free to every high school in the U.S. to hope stem the negative effects of opioid overdose.

The program requires a commitment from schools to training SROs and school nurses in how to administer the life-saving nasal-spray. Some schools have declined because first responders, who also have access to Narcan, are nearby. Rules and reactions have varied state to state, and even district to district.

Some districts, like Hartford, Vermont schools, initially didn't want to stock Narcan due to liability concerns. Nevertheless, an ongoing increase in drug use and a rash of overdoses later made district officials there change course.

Last year, New York updated legislation in order to allow nurses to administer naloxone in schools without liability; Kentucky laws allow the same. Maine Gov. Paul LePage, however, has twice vetoed legislative proposals related to Narcan in schools, saying that it encouraged a false sense of safety in users.

In New Hampshire's K-12 Hampton schools, district officials chose not to stock Narcan, saying school nurses weren't "equipped" to deal with any side effects and that local drug use was more of a problem for those over age 18. There, too, a local fire station is very close by.

Rhode Island has the most aggressive approach in the country. The state requires Narcan to be available in all middle, junior high and high schools.

According to the state's health department, 29 children ages 17 and younger were administered Narcan between July 2014 and August 2015, though it was administered just once in a school setting.

Cascadden believes all schools should keep Narcan on hand, just in case. "Who wants to see a student die on their watch?" she said. "We certainly don't want to bear that tragedy."

Narcan buys time for emergency workers to respond, Cascadden explained, saying that the key is what interventions or measures are in place to support students after they've overdosed and been given Narcan. "Our hope is to never have to administer it," Cascadden said.

And Mattey wants the drug to be available in all schools, saying as the first line of defense in a school setting, school nurses should have access to medication that "can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose."

She compares the emergency antidote to the emergency use of an EpiPen for an allergic reaction, or the use of an AED in the event of a cardiac emergency.

"If an emergency occurs, school nurses want the tools necessary to save a life," Mattey said. "Often, in the case of using naloxone to reverse the respiratory depression that occurs, the use of naloxone may be the first step on the way to recovery. I can think of no reason why we should not have a life saving medication available in the school setting, especially when we know that we have an epidemic and that our teens are abusing opioid medication."

Looking to higher ed

Colleges and universities have also debated keeping Narcan on hand. A June 2015 report by the Hazelden Betty Ford Institute for Recovery Advocacy and The Christie Foundation surveyed 1,600 college-aged youth and found 16% admitted using pain pills that weren't prescribed to them at least once, with 32% saying that they wouldn't know where to turn in an emergency overdose situation. And 10% of those surveyed reported currently using a pain medication prescribed to them.

At Boston University, campus police began carrying Narcan back in August 2014, making it the first campus in the nation to supply the antitdote.

"We have 33,000 students, and we're certainly in an area where there are individuals who are victims of the opioid situation," said Colin Riley, Executive Director of Media Relations at Boston University. "Fortunately, we don't have any students who have been affected … But our police department carries Narcan."

Others colleges followed suit, including 12 SUNY campuses and community colleges like Sinclair College in Ohio equipping campus police with the antidote.

Key Facts: Attitudes of college-aged youth (18-25)

- Nearly 16% of college-aged students said they have used pain pills without a prescription.

- For athletes, this number increases to 22.5%.

- 34% of college students said they can easily get prescription pain meds; 49.5% say they can get them within 24 hours.

- 86.6% know the meds can be addictive, but 63% see prescription pain meds as less risky than heroin. 11% have taken something without knowing what it was.

- 30.8% knew of someone who overdosed on opioids -- either pills or heroin -- but 37.2% said they wouldn’t know how to get help in the event of an overdose.

- 1/10 had a current prescription for pain meds, and 20.2% said they took more than they were supposed to.

- 20.2% reported using the pills in excess of the dose prescribed.

"SUNY Cortland has already provided training for our police officers," said Christopher A. Kuretich, the Assistant Vice President for Student Affairs and the Interim Chief Diversity Officer at SUNY Cortland.

And across the country, roughly 60 medical schools have also committed to requiring prescriber education for Narcan, beginning in fall 2016. Such instruction will align with "Prevention Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain," issued by the Centers for Disease Control, and will be required in order to graduate.

In North Dakota, University System Chancellor Dr. Mark Hagerott is collaborating with healthcare workers on ways to combat the rising opioid epidemic. This collaboration is just one part of his 2030 plan to address the full spectrum of needs facing students coming through the pipeline into the state's higher education system, he said.

The comprehensive approach to problem solving brings all stakeholders together "in an integrative way ... with a long-term view" and really allows the university system to solve "problems on a human scale," he said.

An ounce of prevention

Kuretich said schools can get ahead of the issue by establishing well-developed prevention and education efforts, and having them in place before students arrive at college.

Whittier Middle School (Maine) Counselor Bonnie Robbins agrees prevention and communication are crucial.

"Words of advice to schools that are starting to deal with the issue of opioid use would be to educate your staff, students and families in the dangers of opioid use," Robbins said. "Don't be afraid to talk about the issue. Don't be judgmental. Build relationships with the students so they are comfortable opening up, especially with the school counselor. Involve local law enforcement, drug agencies, substance abuse counselors to be part of the conversations."

Some school systems and district administrators have turned to public awareness campaigns designed to call attention to the issue. In Worcester, Massachusetts, a series of 13 individual PSAs in English and in Spanish were broadcast on cable TV and through social media channels.

Moving the needle

At the federal level, legislative solutions are also taking shape. The House of Representatives passed 18 bi-partisan bills related to creating federal grants, rules and studies of opioid addiction. The Senate has also approved a comprehensive bill, spearheaded by New Hampshire Senator Kelly Ayotte. And this March, at the National Rx Drug Abuse and Heroin Summit in Atlanta, President Obama announced expanded access to addiction treatment and $94 million in new funding to 271 Community Health Centers across the U.S., among other steps.

Still, schools across the nation are trying to contend with an issue many educators don't feel equipped to handle, and there doesn't appear to be a widespread consensus on the best way to tackle the issue. When a student at the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth died of an apparent opioid overdose in January, Associate Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs Dr. David Milstone addressed the public, saying, "the prescription and heroin abuse epidemic does not discriminate by zip code, educational level, economic status, race, religion or age. Just as this challenge grips communities across the nation, it affects college campuses as well."

A second tragedy was averted because another student called for help, but according to a recent report by the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation for Recovery Advocacy and The Christie Foundation, 37.2% of college aged students wouldn't know where to turn in the event they or someone they knew was experiencing an overdose.

At UMass Dartmouth, additional counseling services were made available and faculty members were provided resources to help them broach the topic in class. Discussions with student groups to educate them on the perils associated with the rising epidemic were also held by the office of student affairs, all tactics that are appropriate for students of every age level. But as the country continues to experience a rise in the availability and use of prescription drugs, the resources dedicated to fighting its impact on schools will be re-evaluated.

As Salfia wrote, "It's time for our communities and schools to actively and aggressively work to protect our young people and fight back against the tidal wave of controlled substances that are so readily available to them. We can't allow stories like [Mercado-Medrano's] to become our new normal."

Autumn A. Arnett contributed to this story.