Teachers typically listen to young children read aloud individually to assess their early literacy skills. But a new online reading assessment, released this week by NWEA, aims to modernize this process by having students read text aloud from a computer screen or tablet and speak into a microphone to record their voices.

Part of NWEA’s widely used Measures of Academic Progress (MAP) tests, the new MAP Reading Fluency assessment focuses on the “learning-to-read” process and uses voice recognition technology to collect data on an entire class of students in about 20 minutes, the developers say.

The adaptive assessment asks students questions about what they are reading to measure comprehension, a feature that is better than only measuring how many words a student can correctly decode in a certain amount of time, says Cindy Jiban, a former special education teacher and a senior curriculum specialist at NWEA who helped develop the program.

“The ones who can read fast will just read fast,” she says, adding that the assessment includes a “comprehension check as you read aloud.”

Teachers can review the data on a dashboard and play back a student’s recording as many times as they want to better identify where the child might need help.

“These are the kinds of things that teachers of beginning readers are very interested in learning about their kids,” says Jennifer Knestrick, the senior product manager for early learning at NWEA.

But how distracting is it to have 20-some 1st- or 2nd-graders all reading aloud into microphones at the same time — even if they’re wearing headsets? That’s one of the questions Knestrick says the program's developers asked themselves.

“The feasibility of all of this — the tech and the kids and having them manage their own recording — we weren’t sure starting out,” she says.

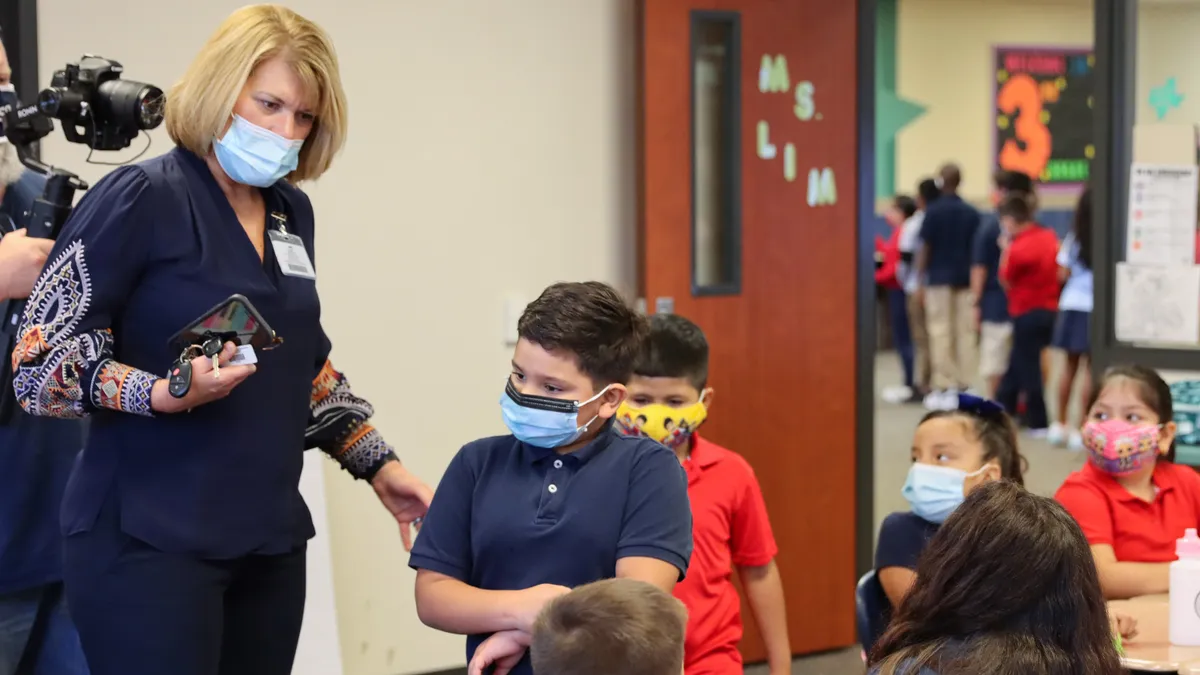

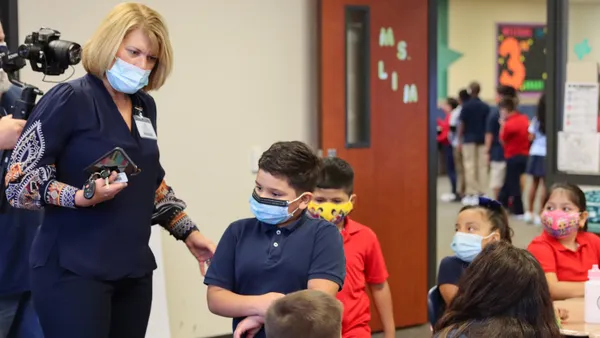

From conducting field tests during the 2016-17 school year with 2,000 students in six states, and now expanding use of the assessment to about 10,000 students in “early-adopter” classrooms, Knestrick says they’ve learned that young children are comfortable reading aloud next to each other and often do that with print books anyway. “They shocked us in that way,” she says, but adds that she still recommends having only about 15 students using the assessment at one time.

Online or in person?

With even young children increasingly reading on tablets, it makes sense that more reading assessment is occurring through that medium, as well — especially since tests linked to the Common Core are given online. In fact, recent results of the 2016 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) — which for the first time included assessments of students’ online reading ability — showed that U.S. students have grown quite comfortable reading and taking tests on a screen. U.S. 4th graders scored behind only three other countries in their ability to navigate their way on a website.

But with young children’s oral reading skills, some early literacy experts and teachers say there is still an advantage to listening to a child read individually.

“The teacher (or some human) still has to find a time to sit down and listen to all the recordings — usually during time set aside for lunch, planning or beyond school hours since they certainly can’t score them when they are teaching,” says Rachael Gabriel, an assistant professor of literacy education at the University of Connecticut.

She adds that other assessment companies have tried similar recording features, and that she sometimes has graduate students use recordings as they are learning how to use assessments — but there are some “questions that can only be answered in person.”

“A brief oral reading assessment given in class provides the added benefit of observing students as they read in order to notice what might have caused a repetition, pause or dropped line of oral reading,” she says. “You can probe and provide instruction at the point of need, and you can develop rapport and relational supports for learning.”

Looking for a 'complete picture'

Research over the past two decades has helped to clarify the primary skills students need to become good readers — the alphabetic principle, phonemic awareness, oral reading fluency, vocabulary and comprehension. But some experts, and classroom teachers, argue that many early reading assessments focus too much on skills such as words per minute that are easy to measure and to communicate to parents and policymakers.

In a 2014 article for the Washington Post, for example, Gabriel wrote that because the Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS) assessment, also widely used in the early grades, focuses on speed and accuracy of reading nonsense words — such as “yud” or “bim” — a student who slows down or tries to make sense of those words can be labeled as needing “intensive” remediation.

Knestrick says the new MAP assessment looks at “multiple dimensions of the child’s oral reading,” including how fast they are reading as well as their understanding of the sentence or passage. “This gives the teacher looking at the results a much more complete picture, and it puts the scores in context. She can identify any difficulties the child is having, but that information is not narrowly focused on rate the way it is with many fluency measures,” she says.

Kathryn Mitchell Pierce, an assistant professor of literacy at Saint Louis University and a member of the National Council of Teachers of English’s Standing Committee on Assessment, adds that district and school administrators might also emphasize the use of a particular assessment if they’ve spent money to have it in the classroom.

With any commercial assessment focused on reading, however, teachers should ask themselves, “Are they defining reading the way I would define it?” says Pierce, who also taught in the early grades for many years with the School District of Clayton (MO).

“As the classroom teacher, not only should I get to know my kids better as readers, I should get smarter about how reading works.”

Multiple measures important

Susana Rios, who teaches a bilingual 2nd grade class at Sonoma Elementary in the Las Cruces (NM) Public Schools, regularly uses both computer-based and in-person assessments of students’ oral reading skills — and sees advantages of both.

The computer-based assessments, she says, generate an individualized report on each student that identifies their reading level and helps her find differentiated literacy and enrichment resources for her students, including English learners, which, she says, is often time-consuming. The online assessments also consider students’ developmental needs, she says,

“In other words, the assessments include cartoonish characters, music, movement and deliver the instructions in slow clear ways,” Rios says. “The interactive experience helps with young students’ attention span. This makes things easier for the teacher, since it helps to keep students focused throughout the assessment.”

But the informal, face-to-face reading assessments she does with her students almost daily give her “current data that no other computer-based program can,” she says. “I can see the eye movement of my students and determine their attention skills. I can feel their breathing and notice if they are nervous or feel relaxed. I can see if they are using their fingers to follow the reading and if they are covering the ending syllable as a decoding strategy.”

As with any academic skill, no one test can provide a full picture of a child’s ability, experts say. This is especially true in early childhood because children are changing rapidly and with reading, because it is a complex, developmental process.

“Several measures, taken together, are likely to more adequately sample the things students should know and be able to do in the achievement domain being measured,” Susan M. Brookhart, a senior research associate at the Center for Advancing the Study of Teaching and Learning at Duquesne University, wrote in an article for the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. “Using more than one measure also helps us recognize performance variations caused by format, timing and other logistical aspects of testing.”

Pierce adds that if teachers want to listen to a recording of their students reading, they can set up a center in the classroom with iPads and let them record themselves “reading something that they have chosen.”

Dive Awards

Dive Awards