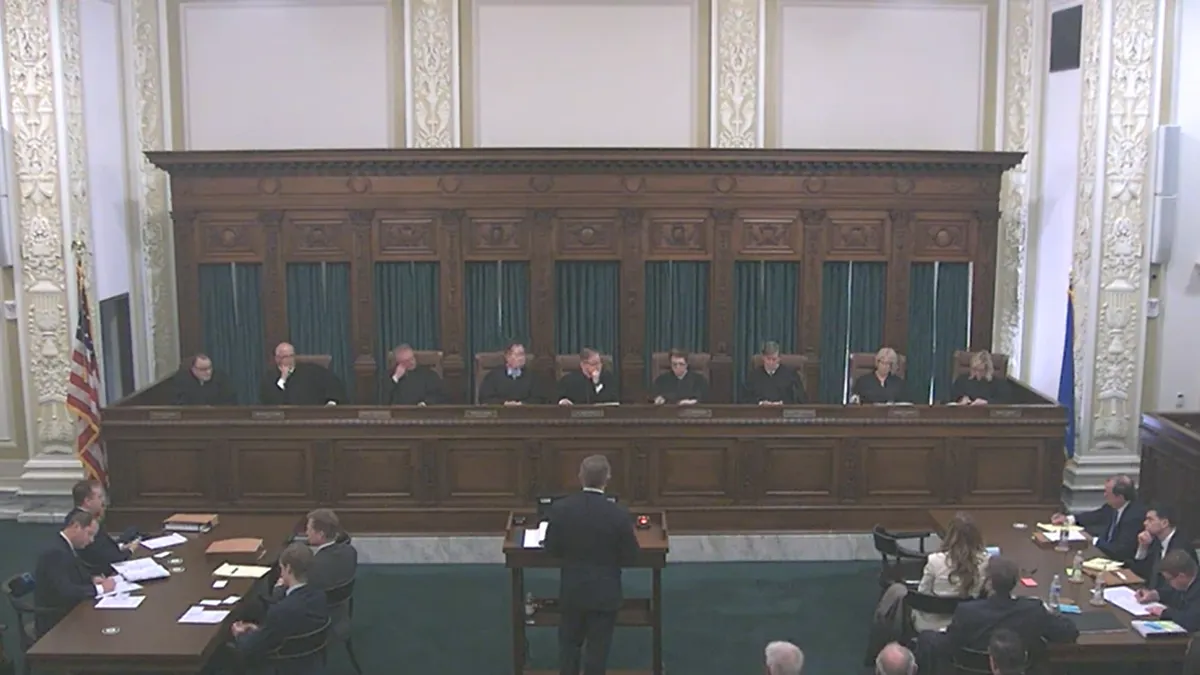

Oklahoma Supreme Court justices seemed split during oral arguments Tuesday in a landmark case questioning the constitutionality of the nation's first religious public charter school.

On one hand, some of the nine justices who heard arguments in Drummond v. Oklahoma Statewide Virtual Charter School Board showed concern about taxpayer dollars being funneled to St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual Charter School.

"This case is about a Catholic school who wants to be fully Catholic funded by public funds," said Oklahoma Supreme Court Justice Noma Gurich. "So where is the choice for taxpayers in Oklahoma not to support the Catholic church, or the Baptist church, or the Episcopal church, or the atheists, or any other church?"

Vice-Chief Justice Dustin Rowe agreed that in this situation "taxpayers are compelled to have their funds spent on behalf of the school regardless of whether their children choose not to go there."

The Oklahoma justices also weighed other concerns, including the school's religious curricula, school board members' religious affiliation, whether the school is a government actor, and how much control the state would have over the nation's first religious charter school.

A divisive case

The case was argued by Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner Drummond, who sued the Oklahoma Statewide Virtual Charter School Board last October, just weeks after the board approved the virtual charter's contract.

Board members, all five of whom are Catholic according to St. Isidore's lawyer, have acknowledged their decision as controversial. In fact, Drummond's predecessor, former Attorney General John O'Connor, directly contradicted Drummond's views when he was still in office.

According to O'Connor, who left his office in 2023 after losing the Republican primary to Drummond, a religiously affiliated entity "must be allowed to establish and operate a charter school in conformance with that applicant’s ‘sectarian’ or ‘religious’ traditions." O'Connor's opinion was precipitated by two key U.S. Supreme Court cases — Carson v. Makin and Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue — that allowed private institutions to have access to public funding regardless of the institutions' religious status or the funds' sectarian use.

O'Connor's opinion, at the time, bolstered St. Isidore's application, said the school's lawyers in the courtroom on Tuesday.

Drummond, however, said in his lawsuit that if St. Isidore were allowed to proceed, "a reckoning will follow in which this State will be faced with the unprecedented quandary of processing requests to directly fund all petitioning sectarian groups."

"For example, this reckoning will require the State to permit extreme sects of the Muslim faith to establish a taxpayer-funded public charter school teaching Sharia Law," he said.

Public function vs. label

On Tuesday, Drummond echoed that sentiment — and more.

Under the Oklahoma state constitution, he argued, charter schools are public schools established by the government and are therefore considered state actors, which cannot indoctrinate the public or teach religion.

"This case is not about the exclusion of a religious entity from government aid, which would implicate the free exercise of religion," he told the justices. "Rather it is about the state creation of a religious school, which unequivocally establishes religion."

St. Isidore would be subject to state rules and regulations that apply to other public schools, such as being required to educate students with disabilities, being prohibited from charging tuition, and receiving and spending funds. It would also be subject to other public school requirements like regular student testing, a 180-day school year, and financial reporting and auditing.

Furthermore, employees of the religious charter would receive the same public employee benefits available to other state employees.

On the other side, the justices heard from Phil Sechler, senior counsel for Alliance Defending Freedom, who represented the Oklahoma Statewide Virtual Charter School Board. While St. Isidore is labeled a "public school," Sechler said, it is not a government actor and only carries the title the way "public" defenders and "public" broadcast channels do.

"All 'public school' means is a free school supported by taxation," Sechler said. "There's no indication that the legislature intended for the [law] to mean a government entity."

In all other areas aside from its "public" title, Sechler said, St. Isidore functions as a private entity, including being organized as a private nonprofit with its own bylaws, officers, directors, equipment, bank accounts, contracts and employees, including a principal who reports to its own board.

"The state did not create that," he said.

The state would also be discriminating against St. Isidore if it prevents the school from accessing public dollars because of its religious affiliation, said Sechler.

St. Isidore to open later this year

St. Isidore is set to open July 1 and already has hundreds of applicants, said Michael McGinley, an attorney for St. Isidore.

"There are a significant number of families that have shown interest," he said.

It would be the nation's first public school with a faith-based curriculum, attorneys agreed. In addition, the principal would be required to be a practicing Catholic and students would have to attend Mass.

“Are we being used as a test case? It sure looks like it,” said Justice Yvonne Kauger, adding that crossing the line between church and state could open a Pandora's box. “When the wall comes down, it’s ‘Katie, bar the door.’ Everyone would be affected.”

It's possible that the case makes its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, as the justices debated the possibility of federal laws superseding the Oklahoma state constitution regardless of what the Oklahoma Supreme Court decides.

"We don't know what the [U.S.] Supreme Court's gonna do — it's not our job to interpret the United States Constitution, it's their job," said Justice Dana Kuehn. "At the end of the day here, it will come down to what the U.S. Supreme Court decides, what these [constitutional] clauses mean."