This article is the second in a year-long series on the experiences of a new principal in the Prince George’s County Public Schools. Read past installments here.

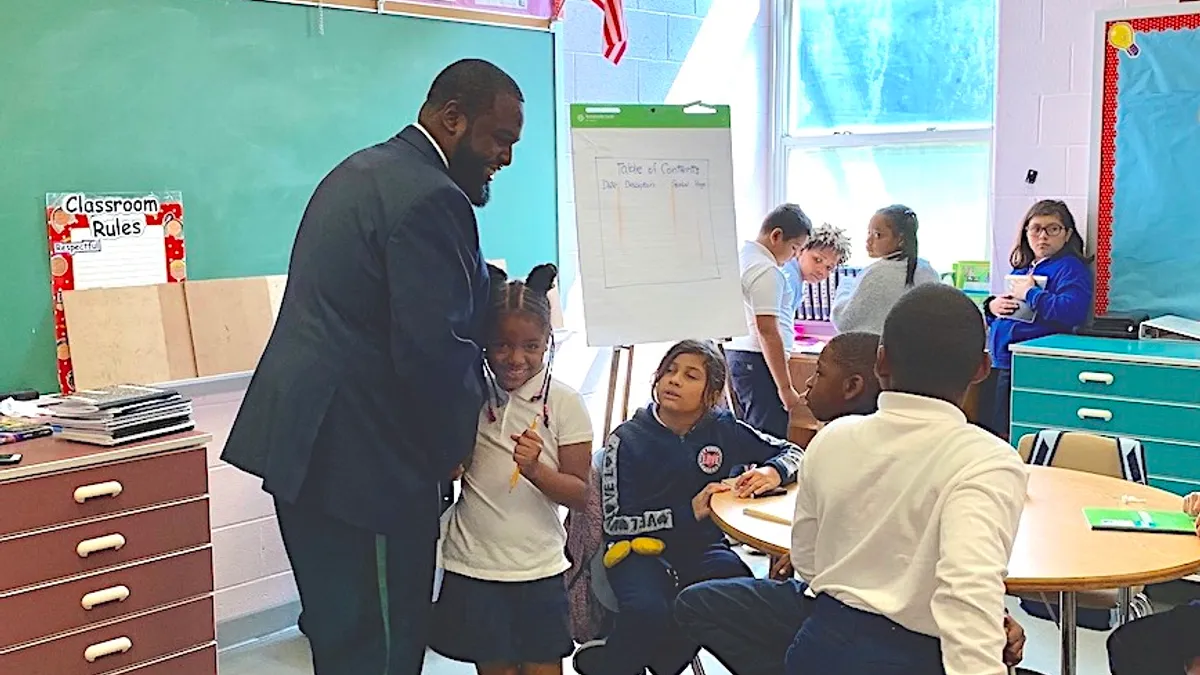

TEMPLE HILLS, Maryland — Walking from classroom to classroom, David Brown completes his morning ritual of greeting every teacher and making sure Hillcrest Heights Elementary School’s students get accustomed to seeing his tall frame around the building.

“Wait, we missed one,” he says, doubling back down the hallway. Finding a few boys in a classroom by themselves, he escorts them to join their classmates and checks the locks on all doors before returning to his office. “I like to look at a school kind of like a hotel. What’s the level of customer service you’re providing?”

He peeks into one space that’s arranged for conversation, with a table and some comfortable chairs. It’s not needed as a classroom, so teachers use it for planning time. “You don’t have vacant rooms in your house,” Brown says, “so you shouldn’t have vacant rooms in your school.”

Ready to roll out new initiatives, Brown is aware that while Hillcrest Heights teachers are receptive to some of his ideas, there are other approaches he would like to introduce that fall under the category of “not yet.”

For example, he’s already got staff members taking the StrengthFinder assessment, which helps them learn more about their talents, discovering the “balconies and the basements of those strengths.” But he’s holding off for now on pushing for more arts integration in the curriculum.

He’s also implementing a character education curriculum he used at another school — featuring illustrations of animals embodying courage, trust or joy, for example. But in a meeting with Assistant Principal Sharon McNeil and other staff members who will oversee the program, he emphasizes that teachers need to see it as a complement to what they’re already doing to encourage students’ positive behavior — not another new program.

“I don’t want to stress them out,” says Brown, one of 17 first-year principals in the Prince George’s County Public Schools (PGCPS) easing into their new positions this fall.

A former 6th grade teacher and assistant principal in the district, Brown is also among more than 350 educators who have participated in the suite of leadership preparation programs PGCPS has implemented in recent years. Creating a sense of stability at Hillcrest Heights while also looking for the “low-hanging fruit” of areas that need early attention is a challenge Brown says was often discussed during his training.

“What are the things that you can change immediately that are not working?” he asks.

Student attendance at Hillcrest Heights — a brown brick school matching the design of the surrounding homes — is one of those areas Brown wants to address right away.

According to the school’s 2017-18 state report card, almost 40% of the school’s students are chronically absent. Other indicators, such as low percentages of students proficient on state tests and significant levels of student mobility, point to some of the challenges Brown will face as he looks for ways to improve student outcomes.

“I’ve got to own what has happened,” he says. “The data is what it is. We decide whether to stay there.”

He’s hoping to incorporate incentives into the school’s positive behavior program to encourage regular attendance. And in addition to greeting everyone, every morning, he wants to institute a “lunch bunch” as a way to build rapport with students.

PGCPS, with more than 130,000 students, was one of six large districts nationwide that participated in the Wallace Foundation’s five-year effort to improve the training and retention of principals. Because of that work, the district created a progression of leadership preparation programs taking prospective school leaders through two years of assistant principal induction and a principal training program — Aspiring Leaders Program for Student Success (ALPSS) — which Brown refers to as a “year-long job interview."

"Every year we improve the selection of candidates for our pipeline preparation program and they turn out to be even better instructional leaders once they complete the program," says district CEO Monica Goldson. "As we have found during the interview process, candidates who have gone through the principal pipeline often have an advantage due to the on-the-job support they received on the road to becoming a principal leader."

Never 'fully ready'

Brown spent his ALPSS year at Fort Washington Forest Elementary, working alongside veteran principal Mark Dennison. But even with that exposure to the daily demands of administration, Brown says, “I don’t know if you’re ever fully ready for the principal seat. Some learning just happens in the seat.”

“I don’t know if you’re ever fully ready for the principal seat. Some learning just happens in the seat.”

David Brown

Principal, Hillcrest Heights E.S.

His selection for the position at Hillcrest Heights also involved a panel interview that included members of the community — a practice instituted by Goldson.

"Many times, our community believes that we select principals in a vacuum without taking into consideration their input and needs," she says. "Including parents and staff has helped to shed light on all aspects of the selection process, including the complexities of a school leader’s role."

During the hiring process, Goldson also refers to what the district calls “baseball cards” — a summary of input from staff and community members.

“It lets you know right there what is important to those individuals, what they are looking for in their next principal,” Brown says.

Avenues for growth

Establishing a schedule for informally and later formally observing teachers is another aspect of Brown’s early work with McNeil, who has been at the school for nine years.

“Always find two to three positive things to praise,” he suggests.

He’s also brought with him some tips for storing and sharing documents related to observations, which McNeil says are already more efficient than practices the school was using. But she added that Brown is also respecting existing structures and schedules for meetings.

“He just understands,” she said. “He didn’t come in saying, ‘I don’t like Tuesdays. I want Wednesdays.’”

Brown admits, however, that handling the financial aspects of school leadership is his “biggest avenue for growth.” He’s calling on officials in district offices that he says he “never knew existed.”

He tries to stay in touch with the other first-year principals in his ALPSS cohort. After their first week of school, they met together for dinner. And he has regular check-ins with Dennison, his mentor, who even after 18 years as a principal says he’s still facing situations new to him.

The district has also strengthened the mentoring role. When he was a new elementary principal, Dennison says he was paired with a high school principal. Now the district pairs rookie principals with a “job-alike mentor” so the advice is more relevant.

In addition, the district’s mentors are now required to complete an extensive certification program through the National Association of Elementary School Principals, which Dennison says keeps him fresh and allows him to continue “developing as an older principal.”

Brown, Dennison says, “already knows that when you first go into a building, you want a collaborative approach,” and for the “staff to know we are going to work through this together.”

And Dennison emphasized that customer service mindset recently when Brown consulted him about a parent’s request to move their child to a different class. “At the beginning of the year, it’s easier to move,” Dennison said. “That shows good faith. Parents appreciate that more.”

‘Always time for music’

Finding balance doesn’t stop when Brown leaves the building. Married, and with a toddler at home, Brown said he’s tried to be as “transparent” as possible with his wife about when he’ll be home and how the job will seep into his evening.

While working as an assistant principal at Capitol Heights Elementary, Brown said he had “figured out the appropriate balance between work and life.” But now he has an almost 2-year-old, David Jr., "who is going to walk up and close the laptop.”

He’s also finding it harder to get to Washington Nationals baseball and Wizards basketball games, as well as some local games in the county. But he says “there’s always time for [listening to] music” — his other favorite off-work activity.

He has settled on finding ways to “recharge and reconnect” with his family during dinner and playtime with his son before returning to the unread emails in his inbox later in the evening.

“The work is the work, but why you do the work is the most important,” Brown says. “And I do it for the children, so they have better opportunities than I did growing up.”

Dive Awards

Dive Awards