The challenge: The School Administrative Unit 6 in Claremont, New Hampshire, located next to the Vermont border, has just a handful of students who have vision impairments and require specialized instruction and supports. But because of the school system’s small student population of 1,500, it was difficult to retain a full-time teacher of students with visual impairments, known as a TVI, said SAU6 Director of Special Education Ben Nester.

Only 0.4% of students with disabilities nationally have their primary disability categorized as visually impaired, according to the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services’ 2020 Annual Report to Congress. The same report said nearly 70% of students with visual impairments spend 80% or more of the school day in general education classes. Because students with visual impairments study the general education curriculum, those teachers need to have the knowledge and resources to best support those students through the guidance of TVIs.

There is also a nationwide shortage of special education teachers, including TVIs, who must have a general or special education degree plus additional coursework and certification depending on state policies. Several people who work in visual impairment education say retirement of TVIs is part of the reason for the shortages.

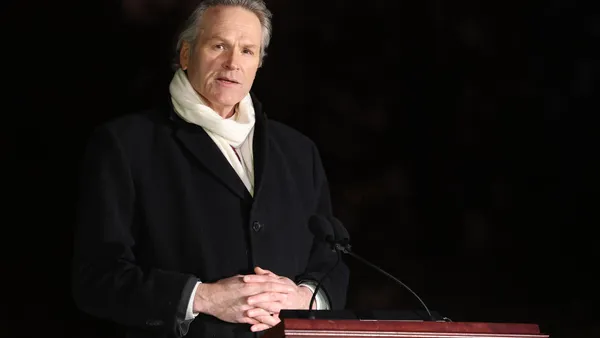

“There's a bit of a crisis in educating children who are blind or visually impaired across the country,” said David Morgan, president and CEO of Future In Sight, a New Hampshire nonprofit that supports people of all ages who have sight loss. FIS also employs TVIs who are contracted to work with students in school districts as itinerant educators.

But it’s not just a lack of TVIs that’s a problem, Morgan said. There’s also a need to improve the teacher preparation experience so teachers are ready to assess students’ needs and provide them all the specific supports for performing at the best of their abilities, he said.

Students with visual impairments are a heterogeneous subgroup. They may be fully blind or have varying degrees of low vision. Some may have had full vision at one time, while others never had sight. Some students may need five or more hours a week of one-to-one time with a TVI; others may require just a half-hour, said visual impairment professionals.

The approach: FIS partnered with University of Massachusetts Boston’s School for Global Inclusion and Social Development in 2018 to recruit and train prospective TVIs and orientation and mobility specialists. Those teachers-in-training have their tuition covered by federal grant monies and FIS scholarships, Morgan said. So far, only a couple teachers have gone through the FIS-sponsored program, but FIS hopes to recruit more teacher candidates.

Sherry Burbank, director of youth services for FIS, helps coordinate the TVIs' work in school districts, which pay FIS for those services. Currently, about 10 TVIs from FIS work with about 125 students from ages birth to young adulthood in New Hampshire, she said.

The TVIs also help train general education teachers and inform parents on individualized instructional strategies and assistive technologies, Burbank said.

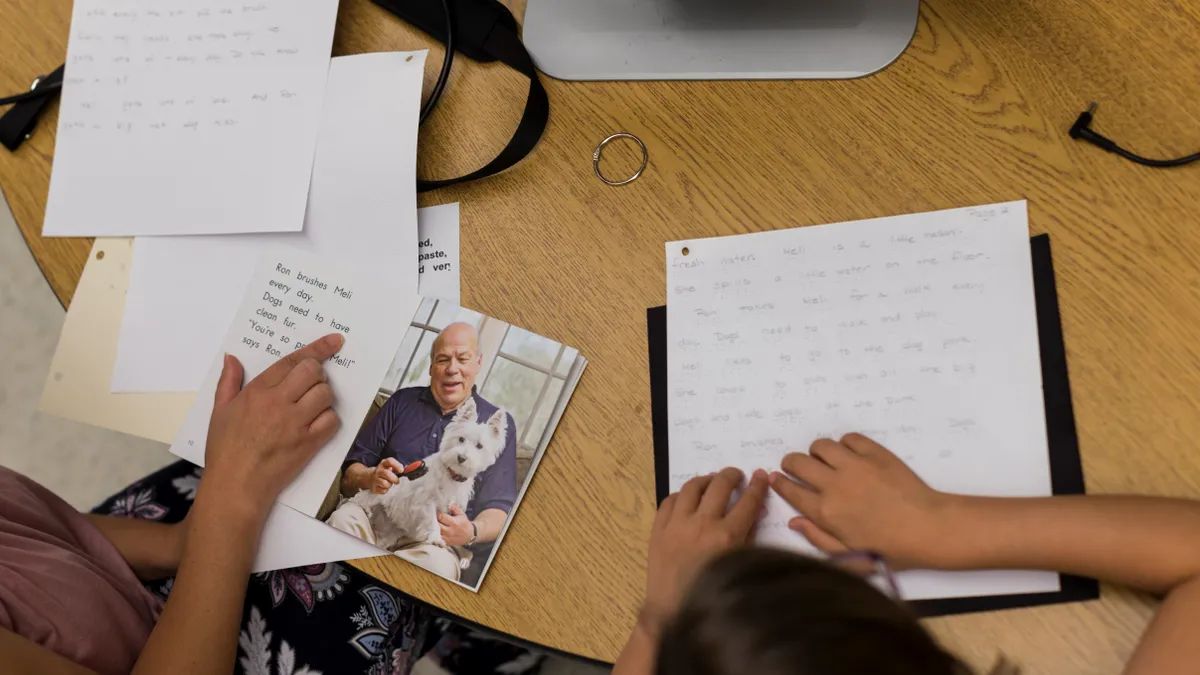

Nester said TVIs’ consultation with general education teachers and parents has been particularly helpful. He also said having the expertise of the TVIs is critical to providing students the services detailed in their IEPs. For example, one student in the district is currently working with a FIS teacher to learn how to use a Braille typewriter to create Braille documents.

“To simplify it, there’s no other option to meeting students’ needs if you have a student-centric approach,” Nester said.

Erika Teal was a paraprofessional at a New Hampshire school district working with a student with visual impairments three years ago when she became interested in further training to become a TVI. After two years of coursework and practicum at the University of Massachusetts — paid for through the FIS scholarship — she earned her masters in education with a focus on supporting students who are blind or have low vision and was hired by FIS.

In addition to working directly with nine students in several different districts and helping them adjust to different assistive technologies, she spends much of her time consulting with the students’ other teachers about their technologies and accommodations, and even explaining what it means to have a visual impairment.

“I really feel like I get to be almost an ambassador on behalf of the students, where I can help everyone on the team, including parents, understand what those needs are and ways to address them,” Teal said.

FIS is also researching approaches in practices that would help students get all the services they need. Morgan calls it a “research, action and advocacy” approach.

For example, he said for vision impairment education, there is an expanded core curriculum that includes nine elements for specialized instruction. However, students often aren’t evaluated on all nine elements, Morgan said.

FIS’ full effort to strengthen evaluation and instructional services began in spring of 2020. The first part of its research is to understand where the gaps exist when students are first evaluated for services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, Morgan said. Then, focus will be placed on best practices for the development of each student's individualized education program. Lastly, FIS wants to help TVIs become better advocates on behalf of students’ needs, Morgan said.

Areas of considerations: Schools can’t deny special education services that are included in a student’s IEP based on costs or conveniences. But sometimes, logistics and expenses can challenge a district’s ability to offer or provide services.

Morgan said he understands districts’ financial challenges, but the research FIS is conducting to better understand students’ needs will help school systems and others advocate for improvements in education policy and federal and state funding.

“Some of us don't believe that a child with a significant disability like blindness or low vision can get an adequate education with an hour a week,” Morgan said. “We believe that a child deserves more than an hour of service, but how do you demonstrate that, how do you justify it, how do you fund it?”

When asked how SAU6 keeps a sustainable partnership with FIS, Nester said, “We pay our bills on time.” He also added much work goes into negotiating agreements on costs and services with FIS’ teachers, and that he seeks advice and information from other special education administrators about their approaches to contracting for IDEA services.

What's next: The work toward strengthening the evaluation process is ongoing, and FIS plans to take what it has learned so far and apply it to evaluation, IEP development and advocacy practices starting this fall, Morgan said.

“For us, the outcomes will be: Are we finding that kiddos are getting more time in their IEP to serve their needs? So it's easy to measure the outcomes,” Morgan said.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards