LaTonya Goffney is superintendent of the Aldine Independent School District in Houston, Texas. Sonja Santelises is CEO of Baltimore City Public Schools. Iranetta Wright is superintendent of Cincinnati Public Schools. All three are members of Chiefs for Change, a nonprofit bipartisan network of school superintendents and state education leaders.

America is finally acknowledging a harsh truth: The way many schools teach children to read doesn’t work. Educators, and indeed families, are having a long overdue conversation about how one of the nation’s most widely used curricula, “Units of Study,” is deeply flawed — and where to go from here.

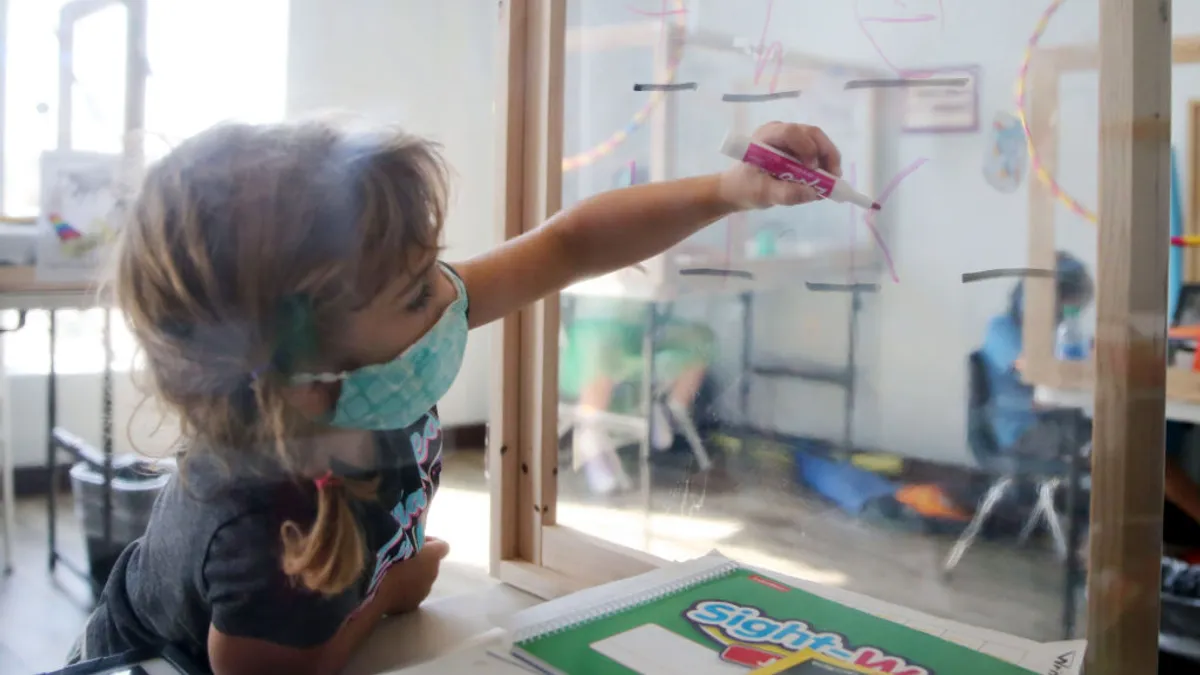

The problem became a mainstream topic of conversation after parents got a closer look at their children’s lessons over Zoom during the pandemic, and journalist Emily Hanford released a podcast exposing how schools and teachers were “Sold a Story.”

As Hanford explained, “Units” was not crafted on the science of reading — or what research shows are the best ways to build literacy. Such research-based methods focus on developing content knowledge, an understanding of letter-sound and sound-spelling relationships, word recognition, and language comprehension and fluency. Multiple, rigorous studies over 40 years prove these are the most effective ways to teach reading.

Yet “Units” instead encourages children to “cue” their thinking by looking at pictures or other words on the page to figure out what they don’t know. This approach is wholly inadequate — it does not build knowledge and skills, is especially problematic for children with a limited vocabulary, and often amounts to little more than guessing.

But the “Units” curriculum has been popular, championed by respected voices, and too few teachers know about or study the science of reading as part of their preparation programs and professional development. Many administrators have also assumed that instructional programs peddled to their districts have a solid research base and are supported by data.

We lead school systems in different regions of the country—the Mid-Atlantic, the Midwest and Texas. And we’ve all seen the instructional disconnect. When LaTonya was new to her position as superintendent of the Aldine Independent School District in Houston, she remembers how a certain curriculum provider was treated like a rock star during a training and thinking, “This just isn’t right.” That’s because Aldine’s poor reading scores made clear that the provider’s curriculum wasn’t working. Troubled, LaTonya started looking into what other districts were doing and connected with Sonja, who is CEO of Baltimore City Public Schools.

For her part, Sonja had long known that widely adopted methods lauded by so-called experts did not deliver for children, especially children of color. She recalls her days as a graduate student, taking the train from Teachers College on Manhattan’s Upper West Side to her student-teaching assignment in the predominantly Black Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn. In those classrooms, Sonja saw firsthand that what her professors were telling her to do was a disservice to children.

Iranetta, who is superintendent of Cincinnati Public Schools, had similar thoughts. During her time as a principal, she, too, questioned the misalignment between the claims of well-regarded instructional programs and their actual effect on students who were not grasping foundational skills and becoming strong readers.

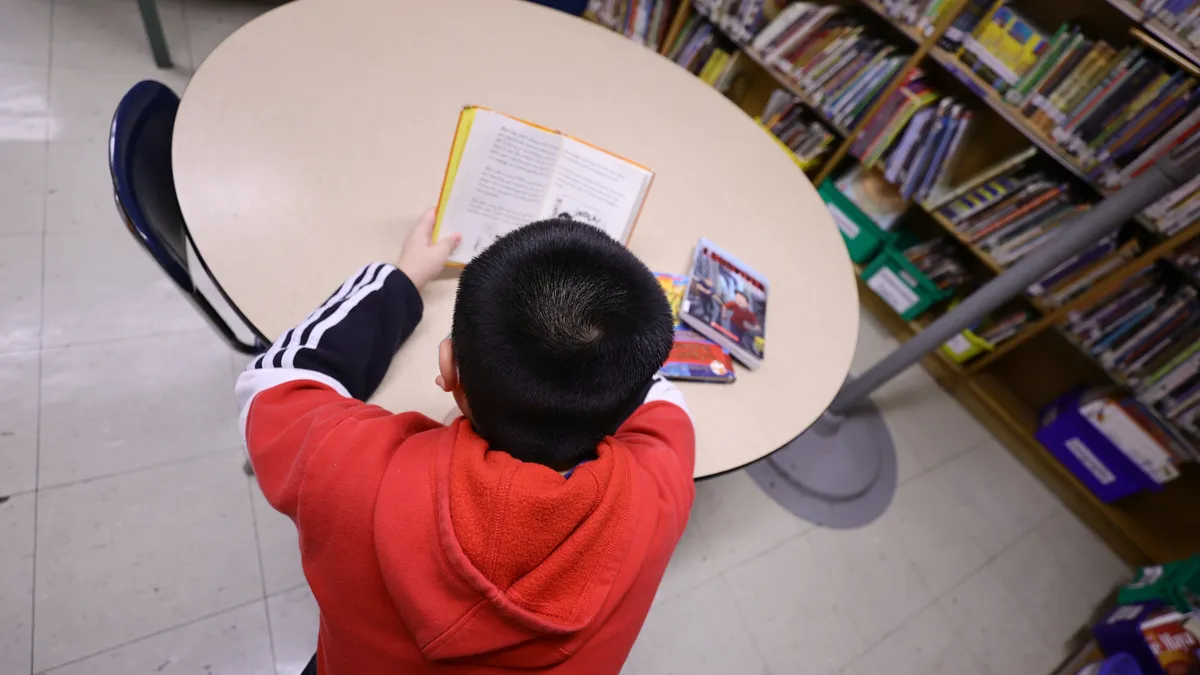

The cueing method is a bad way to teach any child to read. But it is especially wrong for children of color and those from low-income families. Students who are exposed to a lot of language at home — whose families read to them and supplement their education with opportunities like camps and tutoring — have a better chance of becoming capable readers even with shortcomings in their school curriculum.

But for children who don’t have extra support at home, curricula like “Units” can prevent them from ever developing the basic reading skills needed to succeed as an adult. This is a tragedy. It has happened to many children over many years, and it must stop now.

As superintendents, we have to be the instructional leaders of our districts. That is, we must have an instructional point of view. Superintendents must really know the curriculum: What are students actually learning? How are teachers teaching?

We must ensure curriculum, professional development, and coaching are aligned to the science of reading. When we visit schools, we must look for that science in teaching practice. When we meet with our curriculum directors, we must study implementation. And when we plan our budgets, we must allocate resources to support this way of teaching. Our instructional leadership responsibility can’t be delegated to staff or deferred to preserve the status quo. It is at the heart of our mission to educate children.

Our districts overhauled our English language arts curricula. We conducted audits to get a thorough understanding of the materials children were using and where there were gaps, both in the instructional methods and the content itself. Next, we studied alternative options to assess depth and sequence of content knowledge, accuracy and academic rigor. We then selected new materials that provide foundational skills development and high-quality texts that help students build knowledge through content-rich and integrated reading, writing, speaking, listening, and language experiences.

Now, our focus is on training teachers to use the materials effectively so students — all students, no matter what their home life is like — have a level playing field in the classroom. There is still a lot of work to do, but replacing a program that was hurting our children with something better was an important step forward.

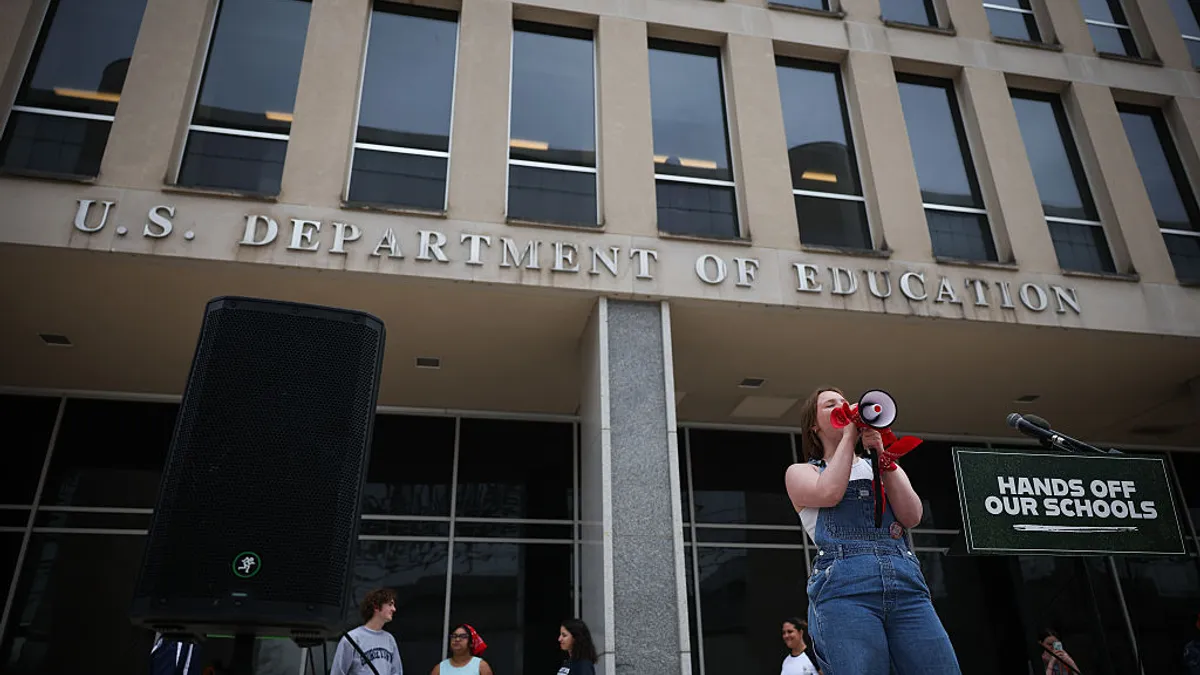

Every district in America should do this, and superintendents should lead the charge. The most recent edition of the Nation’s Report Card showed steep declines — and we can’t just blame the pandemic. Reading scores in 2022 were no better than they were in 1992, a damning indictment on an education system unable to improve reading outcomes over 30 years.

Superintendents can begin to reverse these trends by examining the ELA curriculum. But we can’t stop there. We need to study every subject, in every grade, to make sure we are using programs that work for students, that are grounded in the science of how they learn, and that set them up with the solid education schools are supposed to provide. Otherwise adults will make the same mistake, and children who need us will once again pay the price.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards