In a routine cleanup over the holiday break, the IT department in Michigan’s Richmond Community Schools "noticed something unusual” with the district’s computers. It was a ransomware attack — something districts are becoming all too familiar with.

"Immediately, they shut down the portal where [the virus] had entered the system, shut down other servers that we believe have not yet been infected, and disconnected the internet," Superintendent Brian Walmsley said. "We tried to preserve what was still good and spent the weekend trying to figure out how big the problem was."

While the district confirmed no student or staff information was breached, the ransomware virus impacted several district servers and "affected critical operating systems" including heating, telephones and classroom technology.

The attack mostly infected teachers' saved files, such as curriculum plans and textbook chapters, Walmsley said, and its source demanded $10,000, which the district refused to pay.

Thanks to a daily backup housed in a separate building that was "disconnected immediately" after discovery of the attack, the district restored phones, operating systems in the classrooms and the internet. Restoring teachers' files "will come at a later date," Walmsley said, noting the district is "trying to make sure that we don't reinfect the systems."

Schools are expected to reopen Monday after an extended closure following the break.

How to protect against cyberattacks

While the district in this incident ensures no student or staff data — stored in a separate county-level building — has been compromised, K-12 cybersecurity expert Doug Levin said in most cases "it can be very difficult to know whether or not there has been a data breach."

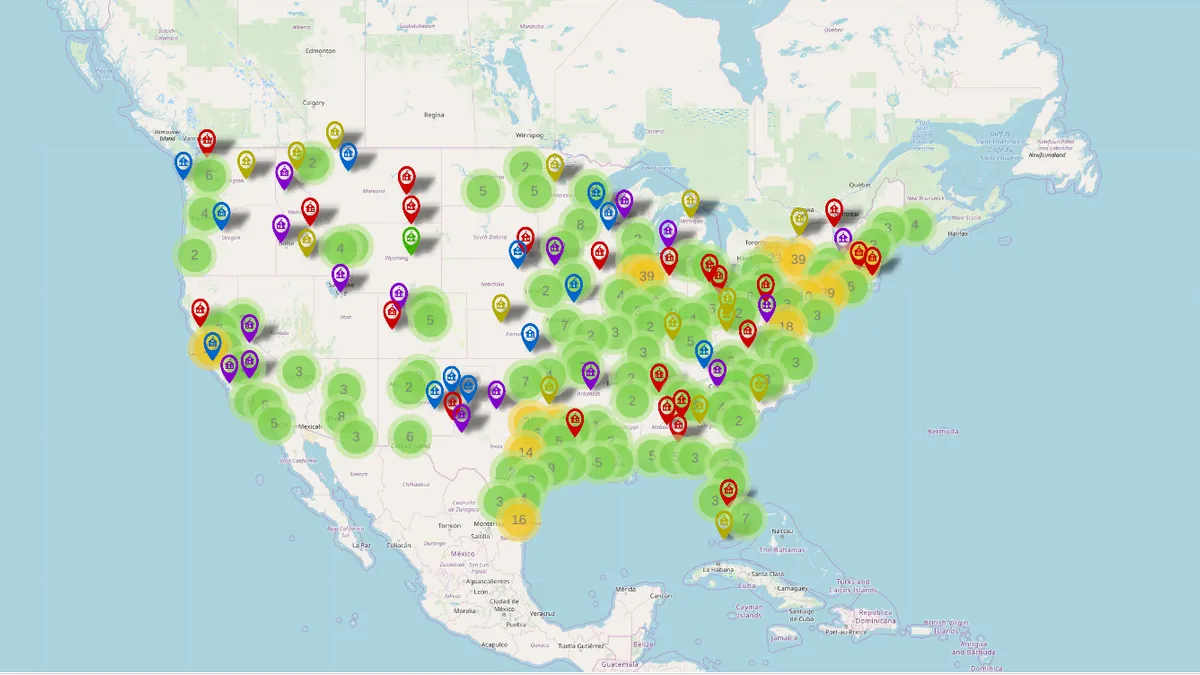

According to Levin, Richmond Community Schools' attack is one of 746 publicly disclosed incidents targeting schools since 2016, a number that has climbed significantly from 408 around this time last year and has affected both large urban districts and smaller rural schools. Washington’s Issaquah School District 411 also reported a malware attack this week.

As more schools incorporate technology in the classroom, and depend on it for everyday functions like payroll and heating and cooling, potential vulnerability for attacks increases.

"School leaders need to weigh the potential benefits of technology with the potential risks that they introduce, among those are cybersecurity risks," Levin said. "And they need to have a plan in place to manage these risks."

This could include keeping a cybersecurity insurance policy or regularly auditing.

Walmsley said in his district's case, it could've been as simple as regularly changing and strengthening passwords, something Levin agrees can mitigate risk.

Routinely backing up systems and keeping them offline, or "immutable" — meaning the backup cannot be altered by a virus — could also save districts time and money in case of a cyberattack. "If you don't have these backups, you're talking about rebuilding these systems from scratch or negotiating with the actors," Levin explained, pointing to a case last year in Riviera Beach, Florida, where the city paid hackers $600,000 to regain access to their systems.

Schools should also evaluate their tech inventory to determine whether they need as many internet-facing servers and systems — not doing so means a school could increase the odds of exposing data.

Regularly keeping up with security updates and patches from software vendors takes time and energy, but is another straightforward process that can go along way to secure systems.

While there's no one way to mitigate risk entirely, "School districts that have plans in place may discover them quicker, may recover quicker, and they communicate about them better to the school community," Levin said. "It helps them maintain trust. "

Dive Awards

Dive Awards