Dive Brief:

- As schools implement systems to check students for coronavirus symptoms, administrators must ensure Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) guidelines when disclosing any information about students, District Administration reports.

- In developing a coronavirus reporting plan, administrators should clarify FERPA rules to staff and remind them that under the law, school districts must acquire written parental permission before sharing a student’s information.

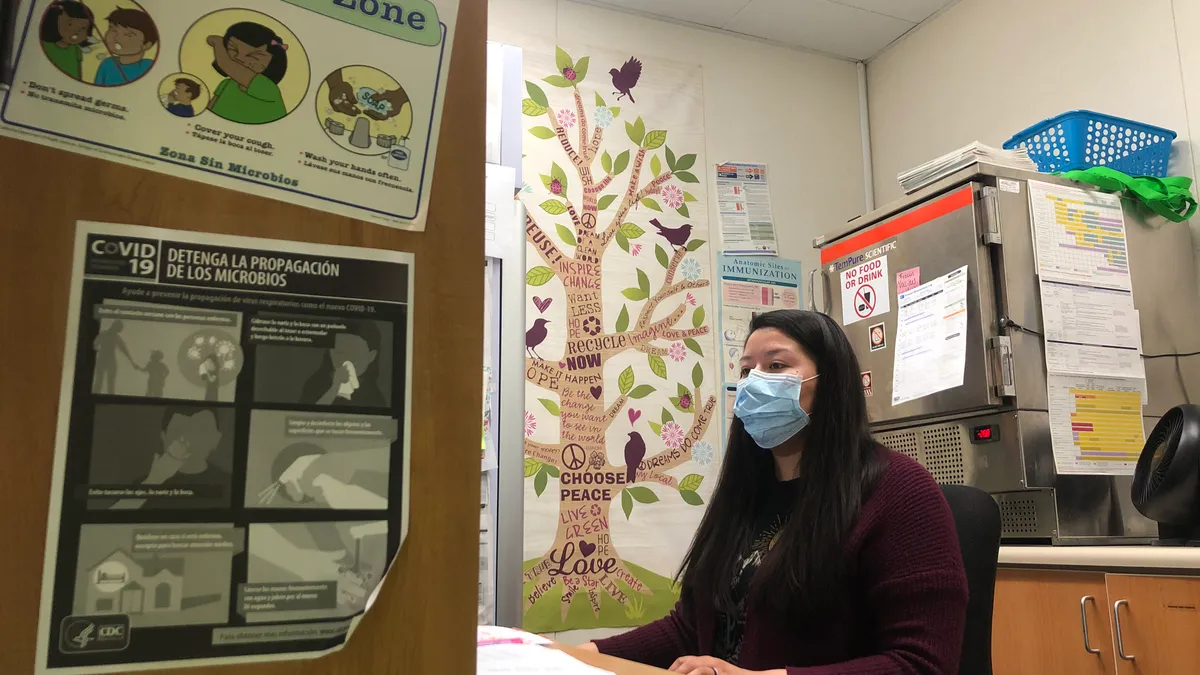

- During health and safety emergencies, districts can disclose information to public health officials, but it can’t be released to the general public without written consent from parents. Staff should also be reminded not to discuss a student’s symptoms verbally, through texts or emails — and to further maintain student privacy, health screenings should be done discreetly, preferably in partitioned spaces.

Dive Insight:

Administrators will need to navigate new protocols this fall when schools reopen during the coronavirus pandemic. The Tennessee Department of Health recently released a “Health Matrix” to help school administrators report cases. The scenarios include: no cases in the building, identified cases, two or more unlinked cases, multiple linked cases within 14 days, and an increasing number of cases within a 14-day timeframe. All communications must conform to FERPA regulations, which cover students but not staff. However, in some cases school officials may deem it appropriate to share a student’s COVID-19 diagnosis with other families.

The Future of Privacy Forum and AASA, the School Superintendents Association, recently teamed up to provide guidance on student privacy during coronavirus shutdowns. While pointing out that health and safety emergency exceptions to FERPA apply during the pandemic, the organizations suggested, information should still be reported in a general way that doesn’t draw attention to a single individual.

For example, if a freshman on the varsity basketball team tests positive for coronavirus — but there is only one freshman on the team — administrators should leave out the age detail to give the student as much privacy as possible. Also, schools can share information with the student’s healthcare provider if parents are unavailable, but education records must continue to remain private during the health crisis.

Though the school year has not yet started, schools are already dealing with this privacy issue. In Georgia, five Carrollton High School football players tested positive for COVID-19, but their identities will not be released due to FERPA. In another recent example, Big Ten universities are releasing the number of cases among athletes, but not identifying students. Clemson University, for example, reported more than 40 positive cases among student athletes and staff but gave no information as to which individuals were infected.

As communication in and between school buildings has gone increasingly digital, taking steps to maintain student privacy has become all the more important.

Last year, the Center for Democracy and Technology argued school districts should hire a chief privacy officer to protect student data and oversee privacy policies. Denver Public Schools has a data privacy officer who makes sure the district complies with FERPA, COPPA and CIPA, as well as state student privacy legislation. In Maryland, Baltimore County Public Schools created this position in 2016 to deal with the increasing role of technology in the classroom. Its director of innovation and digital safety works with its legal team, oversees the movement of data and maintains a data-sharing agreement.