“As a 14-year-old young lady, I feel as though it is my civic duty to make you aware of this issue that is oppressing people in my age bracket, and all age brackets of the black community,” one Louisiana student began a 2016 letter regarding the Black Lives Matter movement, addressed to the president. “Yes all lives matter, but all lives are not treated equally and respected, which needs to change.”

Another student, from Indiana, expressed her concerns from the other side of the debate: “I watch the news with [my] parents, and I constantly see that police are being attacked for claims of using brutal force too much.”

These were among more than 11,000 letters students from across 321 schools wrote in 2016 as part of an effort by the National Writing Campaign to encourage youth civic participation. A recent report analyzing the letters submitted to the campaign, collectively titled “Letters To The Next President 2.0,” suggests students wield power as civic agents, and educators can tap into that through carefully crafted civics instruction.

A “one-size-fits-all” approach to civics education, the report suggests, does not do today’s students justice.

According to the report, authored by a group of Stanford University researchers and published in American Educational Research Journal, students expressed concerns on a wide variety of issues affecting society today, ranging from climate change to sexual violence. In some cases, students identified challenges facing their communities, like immigration policies and gun violence, prior to national campaigns calling for change.

While there was not one certain topic that stood out in the analysis as a top concern for students, the letters suggested today’s teenagers are instead concerned about a range of political issues that vary according to socioeconomic and geographic context.

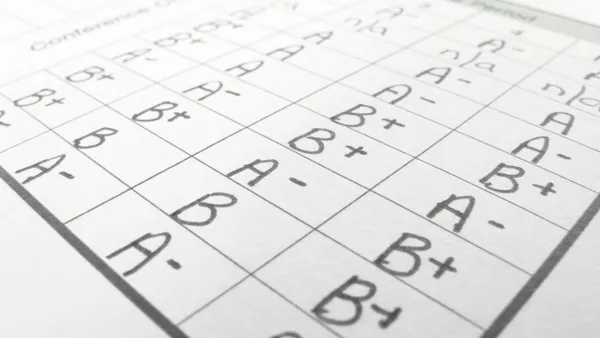

Among the top 20 concerns expressed by students were immigration, guns, education and school-related issues (including school costs), race and ethnicity, and women, gender and LGBTQ issues.

The study shows topics of race and discrimination were more likely to appear in letters written from schools serving a majority of students of color and also a majority-lower-income student population. Topics concerning police were also nearly twice as likely to be present in letters from schools serving majority students of color.

Lower-income communities and communities of color were also more concerned about violence and sexual violence, while “guns” as a topic was more prevalent among more affluent schools and those with majority white students.

School and college costs was also a top concern among students from higher socioeconomic statuses, and authors of the study suggest students from less-privileged backgrounds may have been more likely to express concern on other topics, because while college may be important, it could take a back seat when compared to the daily challenges they face.

Perhaps more important to civic instruction was not writing to the president itself, but the activity that facilitated the expression and exchange of civic beliefs between peers.

Antero Garcia, the lead author of the study and a Stanford University assistant professor, says many teachers “do not feel supported” and may even feel “fearful” about facilitating these kinds of political conversations in classrooms, which he says highlights a “missed opportunity” for educators whose students display “participatory readiness,” or preparation for civic engagement.

“A blanket one-size-fits-all approach to civic education will not do justice to the complex and localized needs in schools,” Garcia points out. “Students have complex civic ideas that schools should explore and help elucidate.”

Patrick Gainey, a civics teacher in South Dakota’s Spearfish High School, says while he is not a big fan of “reinventing the wheel” for a civics curriculum and uses a “We The People” textbook provided by the Center for Civic Education, his conversations in class are often tailored around important political issues facing the nation, including gun control, abortion, the death penalty, birthright citizenship, and search and seizure.

Gainey says his goal for civic instruction is to teach students to develop their independent opinions and be able to listen to opposing views. When it comes to having tough classroom conversations on hot topics, he says he “welcomes disagreement.”

“I tell my students every year the most important thing that I want them to get out of my classroom is the ability to disagree without being disagreeable,” Gainey explains.

He says key facilitators for this instruction are school administrators and district leaders who provide teachers with the resources they need — including laptops, release time for paid professional development training and financial support for competitive student programs. Funding contributions from outside organizations invested in civic education have also helped.

Garcia agrees, pointing out that “reimagining and reinventing” a well-rounded civic education will require extensive support for teachers — who should be attuned to their students’ civic needs — and encouragement of politically-charged conversations students seem ready to have in the classroom.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards