Editor's note: This is part of a four-part series on the challenges schools are facing during the pandemic trying to advance marginalized students and the creative ways they are trying to teach them online and in-person.

In the hour she has between remote classes, Jackelin Escalante Macias' younger brother steps into her room to ask if she has lunch prepared for her five siblings.

“When the pandemic hit, I had to do my own schoolwork and make sure my siblings don't fall behind,” said Escalante Macias, who lives in a rural part of Northern Oregon. “They used to get help from teachers, but now it’s a bit more challenging.”

These days, her schedule orbits closely around her brothers and sisters — she only starts her day’s remote classes after making sure they’ve had breakfast and charged their laptops, and completes her schoolwork once they’ve gone to bed at night.

With her parents at work during the day, the Latina high school student's home is a microcosm of how students are coping in small, rural, low-income districts that are nimbly functioning with limited resources. Umatilla School District, where the girl and her siblings attend, is 100% free meals and 72% students of color.

While rural districts faced many uphill battles during spring closures — including connectivity issues, difficulty maintaining relationships with impoverished students whose parents were working, and delivering meals to families who didn’t have transportation to meal sites — many say the sense of community fostered in small towns worked in their favor.

When Umatilla scraped its hybrid learning plan just weeks before reopening on Aug. 24, Superintendent Heidi Sipe said its size (about 1,400 students) and flexibility helped it swiftly pivot to remote learning. “It’s the beauty of being in a smaller area,” Sipe said.

But seven months into the pandemic, rural, low-income school districts continue to struggle with internet connectivity, large geographic regions, low funding and all the things that challenged them before the health crisis — and now a lot more.

Digital divide comes at steep cost

Rural towns — especially those with large low-income populations — were hit particularly hard by the rush to distance learning in the spring. According to a Pew Research Center survey released in March, rural students were among the least likely to use the internet for homework every day.

The Pew survey showed 65% of students attending suburban schools used the internet for homework every day or almost every day, compared with 58% in cities, 50% in rural areas and 44% in towns.

Access to computers and the internet is a growing challenge for low-income rural students. “The technology divide for kids that are in homes of poverty is real,” said Kyle Sipe, instructional coach for Umatilla and Heidi Sipe's spouse.

Rural districts report the lack of 1:1 technology and home connectivity, and the cost to provide them, as one of the biggest obstacles last spring.

According to a 2017 report released by AASA, The School Superintendents Association, while rural students face greater levels of poverty than their metro-area counterparts, their districts receive significantly lower levels of Title I funding per poor pupil than urban districts. At the same time, rural schools are often expansive, incurring more costs from busing and technology, and face staffing challenges.

Low on funding and tech, administrators in these areas had to get creative during the pandemic. “We put a hotspot in a business owner’s shop that was right next to an apartment complex,” Heidi Sipe said. “We just continually worked with people in the community and business owners to figure out where we could put these internet hubs.”

For the fall, Umatilla purchased more than 400 hotspots for students to take home, in addition to hotspots in neighborhoods. It also utilized a point-to-point system. “We basically beam internet from our school to that location, and it has a router that reroutes the Wi-Fi connection throughout the neighborhood,” Heidi Sipe said.

But sometimes just having an internet connection wasn’t enough for students’ families.

“Where the rubber really hit the road was whether their internet was sufficient to do the online learning — for video calls, streaming, etc,” said Jill Siler, superintendent of Gunter Independent School District in Texas, north of Dallas. Siler said a little more than one-third of her students are considered at-risk and face poverty.

And where rural districts have invested in hotspots or other internet solutions, the added costs are a concern. “You do that at the cost of putting yourself into jeopardy financially moving forward, knowing that the economic outlook is not great,” Siler said, adding her small district has spent $400,000 on ed tech to increase access for students since schools closed in spring.

There are also families so remote and in areas without nearby cell towers, even a hotspot, device and/or extra funding won’t close the digital divide.

La Honda-Pescadero Unified School District, which serves approximately 300 students spread across 175 square miles in California, created “learning hubs” primarily for students who didn’t have connectivity at home and for those with special needs who needed in-person services. Almost 50% of the student population is eligible for free- and reduced-priced meals.

“It’s just all over the place. There’s just no one solution,” said Superintendent Amy Wooliever, whose district is south of San Francisco. “We took over barns, we took over ranches, we opened learning centers at the YMCA camp — places that had internet and tables and shade.”

Staffing concerns exacerbated

The fall has come with new challenges for poor rural schools. In Siler’s district, 85% of students returned to face-to-face instruction, with 15% choosing to remain remote. Those numbers changed as COVID-19 spread after the start of the school year and more students quarantined.

“How do you service all of those students when you are such a small staff that there is no such thing as a stand-alone remote teacher?” Siler said. “We are not large enough to have that efficiency of scale.”

Staffing always is a concern for rural areas at large. Kim Headrick, principal of Whitwell Middle School in Tennessee, northwest of Chattanooga, said one of her greatest concerns during in-person learning this year is the rotation of teachers having to quarantine, leaving in-person students without an instructor.

“What’s hitting our district hard are the substitutes,” Headrick said. "We’re going through that budget really fast."

In Gunter ISD, to take some of the load off staff, the district adopted Edgenuity, an online instructional service, for long-term remote students in grades 6-12 and BrightThinker, a curriculum platform developed by a Texas nonprofit, for grades 3-5 for use without a teacher. Online teaching is supplemented by weekly remote check-ins and daily supplemental teaching for the younger grades.

“For some of those advanced courses, it’s still difficult just trying to help and make sure that students get what they need,” said Dara Arrington, director of curriculum and instruction for Gunter ISD. As a result, the district is conducting home visits, Zoom calls and regular phone calls to provide instructional support for struggling students.

Throughout closures in the spring, students' lack of transportation and connectivity made home visits necessary for delivering meals and traditional paper packets. In the fall, Dawn Guentert, a middle school principal in Umatilla, has made it her goal to visit the homes of all 376 of her students by Christmas. Guentert asks teachers to accompany her on visits, hoping it will “broaden their perspective for some of the environments our kids have been living in and some of the struggles they face.”

“I have just about $1,000 [in] discretionary money that I can use.”

Kim Headrick

Principal of Whitwell Middle School in Tennessee

In Oregon, Umatilla is investing in a virtual tutoring program. The tutors, ranging from college students to the district’s teachers and assistants, are trained to not only help students work through challenging curriculum, but also provide flexible schedules for students who may have to work to help support their families.

During closures, educators say many rural students worked to help support their families, or, like Macias, taking care of their siblings while their parents work long hours. "Our mom is usually gone for work at 4 a.m. and comes back at 6 p.m., and my stepdad leaves at 2 p.m. and won’t come back until 2 in the morning," Macias said.

Like Gunter ISD, Umatilla conducts home visits for students absent from online classes.

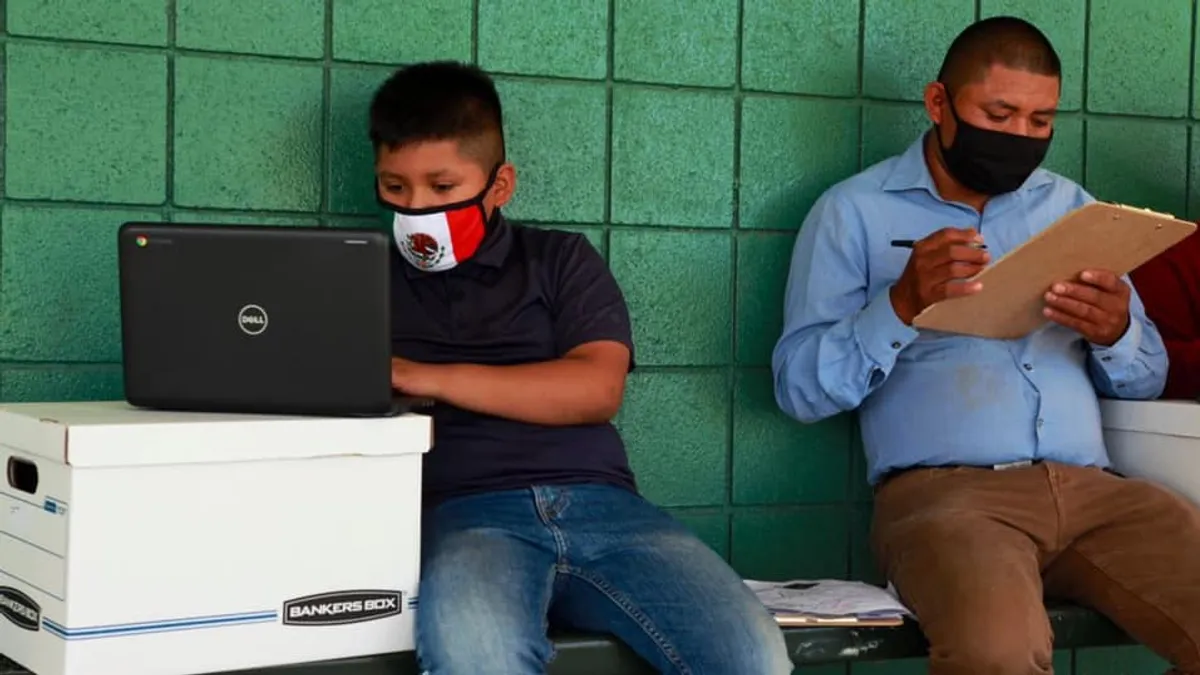

"If they haven’t been checking into teachers’ classes ... that teacher shows up at their front door," Kyle Sipe said, adding the home visits are also a time for mental health checkups and motivating the students. "We hand them a pencil and paper [to do an assignment] and it kind of helps loosen the kid up. We give them simple success like, 'Look, you did an assignment. Now open your Chromebook and do some more.'"

Headrick told Education Dive previously not all her students have parents who can help them with schoolwork, and some "struggle and call us."

"You’re talking about people who are very poverty-stricken," she said. "We have very educated people, but for all those who are educated we have probably two times as many that aren’t."

‘Bracing for the worst’

While some rural districts depended on summer school to keep students on track, others didn’t have the resources to continue those models in remote or socially distanced environments and are bracing for the coming months.

“I’m really anxious to see the state assessment at the end of the year because I think that’s going to help determine how much of a gap we have,” Headrick said. In the meantime, her teachers are pushing forward with grade-level standards, stopping to review past material only when students show learning loss.

“I have just about $1,000 [in] discretionary money that I can use,” Headrick said, of her Tennessee school. “Even if I can get someone to help after school just for one hour a day for four or five days a week, I would like to put that in place. But I’ll try to stretch that $1,000 as much as I can.”

California’s Lindsay Unified School District, south of Fresno, not only is in a rural area, but it's also high poverty, providing 100% free and reduced-price meals. Amalia Lopez, director of special projects, said her district is seeing expected summer slides in English language learners, but those students are making progress at a rate comparable to last year.

Lopez said Lindsay USD will depend on its data dashboard — which tracks teacher training, students’ academic results and learning losses — to inform teacher training as losses become more clear. "You can’t look at [data] in isolation," Lopez said. "We ask ourselves, 'Where and how did teachers get trained and where and how do you see that in student performance?'"

While Gunter ISD, like many other districts, is working on making the 2020-21 year as smooth as possible, Arrington is unsure what it will take in the long term to get students back on track.

“I wish I knew. Is it more time and then an instructional day added?” Arrington said. “Extending our school year so that we have access to students more? I think only time and assessment data is going to tell us.”

“We are bracing for the worst,” said Kyle Sipe, of Umatilla School District. “We’ll be looking at this period two or three years down the road and really be able to see through data where the gaps are for the kids.”

Headrick is also concerned about her few students who have chosen to stay home and are in areas so remote the district is recording in-person lessons, transferring them to USB drives, and having parents pick them up at the end of every week. That leaves students with very little teacher interaction and instructionally one week behind the in-person students.

"At least we’re still able to provide them some type of instruction," she said.

Headrick said she hopes a future private YouTube channel, where the school can upload class videos, will be a "gamechanger" for remote students with minimal internet access. "If people have minutes on their phone, then they can watch or listen to the lessons," she said.

Social-emotional learning ‘a must’

In the meantime, Umatilla’s tutors are not only being trained to support students academically, but also to provide social-emotional support where needed.

“Every time students are experiencing poverty, that’s a priority,” said Heidi Sipe. “But right now, it’s a must.”

Umatilla, which focuses on adverse childhood experiences and building resiliency, is using an early warning and data analytics system called BrightBytes, which flags students at different levels of risk and tracks intervention impacts.

Lindsay USD brought students back to the building as a way to mark the beginning of the school year and offer students a semblance of normalcy. “It was like running seven back-to-school nights all day, everyday,” Lopez said. “We essentially thought: How do you do build culture and community in a safe way, but in a way that would launch the year?”

Nearly all families were able to return to brick-and-mortar by appointment and walk through balloon arches, get pictures taken and eat food. "Reaching our families and learners and providing support has a smaller scale [in a rural district] and has helped us serve them better," Lopez said, adding the caveat that sometimes being a small and rural also means a lack of local partners who are engaged in innovation.

Gunter ISD is also trying to maintain connectedness, from drive-by parades to facilitating students who want to meet their friends in school parking lots while social distancing.

“It’s been multiplied through all of this — the fear that you’ll leave somebody behind,” Arrington said, reiterating it’s all-hands-on-deck to prevent students from slipping through the cracks. “That’ll break an educator’s heart.”