For the past two decades, and not without a bumpy road, achievement gaps for the most marginalized K-12 students in the United States have been closing, if not narrowly.

National report card scores were climbing for both Black and Hispanic students since the 1990s after progress slowed — or reversed in some places — during the late 1980s and into the next decade. Rural schools, despite having lower levels of funding and greater poverty levels, graduated students at higher rates than those in cities or towns. English learners’ achievement, while varying widely across states over the years, slightly increased nationally between 2009 and 2017. Students with disabilities, including those with reading challenges, were projected in 2016 to narrow the achievement gap.

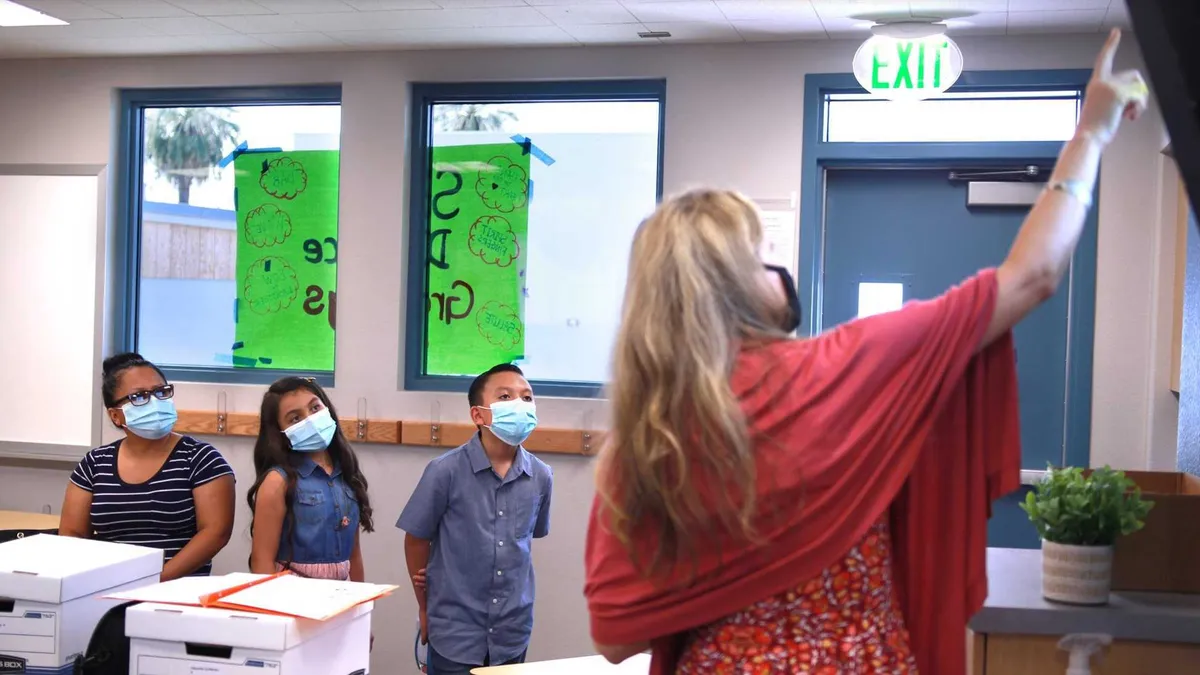

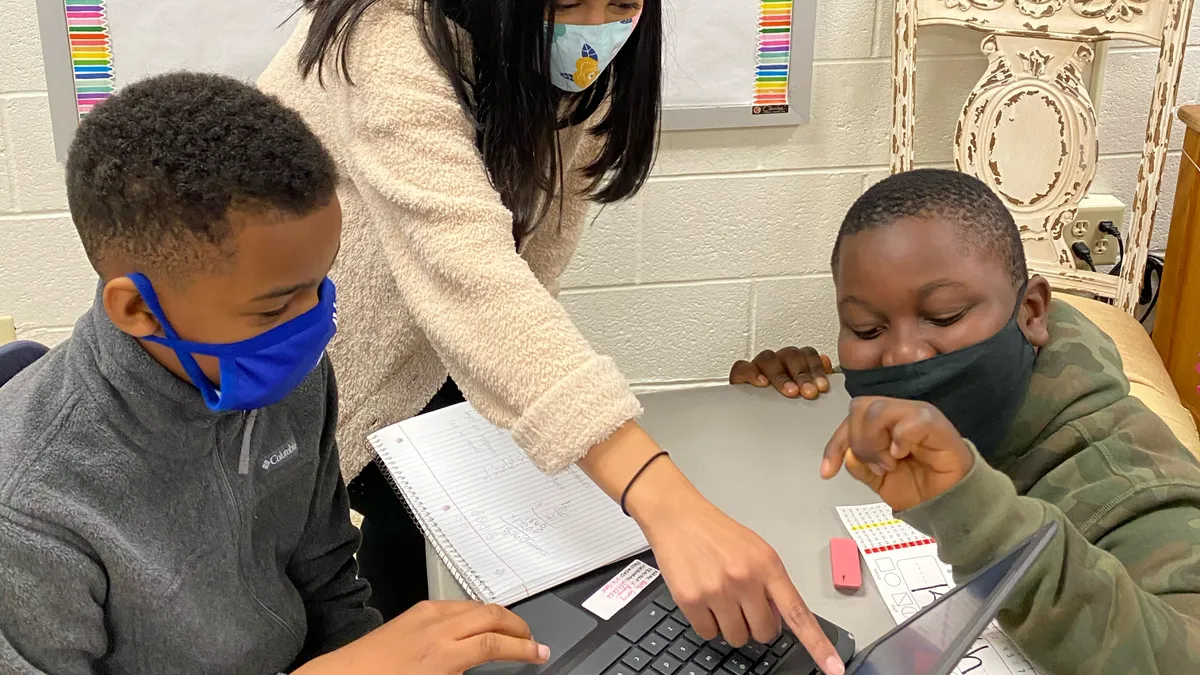

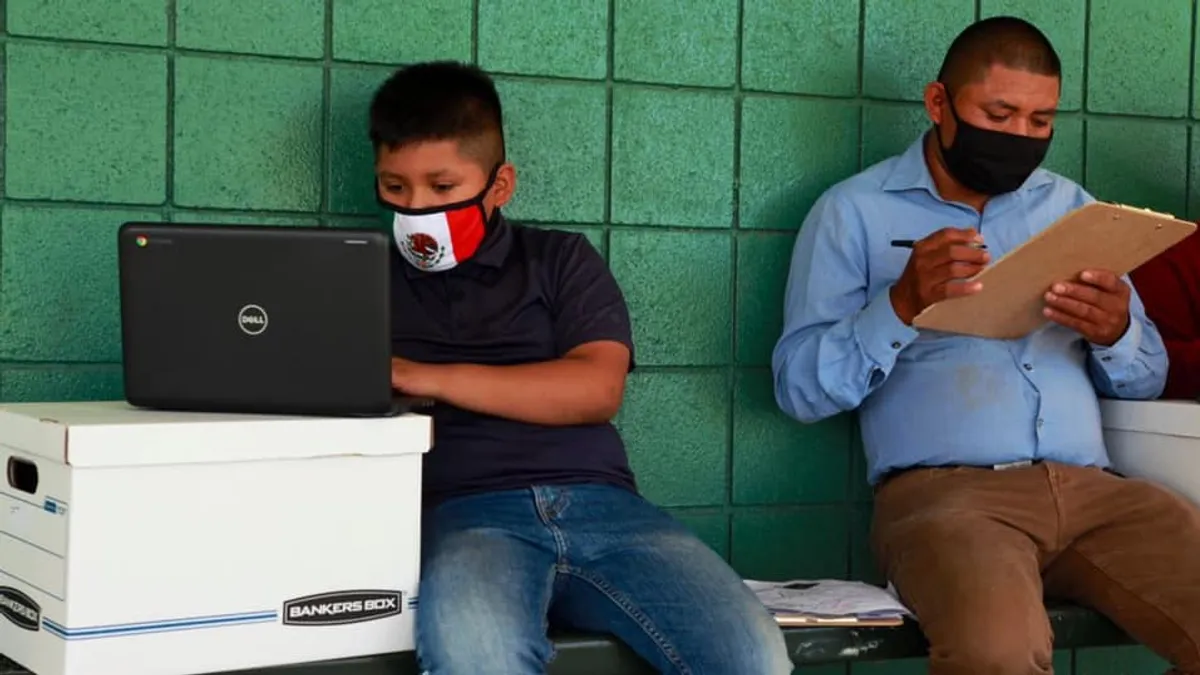

But then the coronavirus pandemic closed school buildings in March. The disruption brought on by the disease put a spotlight directly on inequities in the nation's education system, as schools shifted online and students without technology access and socioeconomic stability — as well as those with disabilities — stumbled.

These marginalized students would sometimes disappear for days at a time or lose out on in-person services, according to educators, while families from affluent backgrounds secured private tutors and organized learning pods for their children.

Many worry the pandemic will widen the opportunity gap in ways that have lasting effects on the state of education. In an effort to recover the learning lost from the spring and buffer a further COVID slide, districts across the country have focused on assessing students’ progress and implementing interventions since the beginning of the 2020-21 school year.

Our Rubric to Recovery four-part series puts a focus on the challenges districts face, as well as the creative solutions educators are developing to bring students back from the margins.