When California’s Sequoia Union High School District considered a credit/no credit grading policy last month, Lora Simakova, a reporter for Carlmont High School’s Scot Scoop, tuned in to a virtual school board meeting to cover the decision.

The sophomore posted her story within a couple hours and ended up having the only local coverage of the decision.

“The parents and community all linked to that as they debated the results on Facebook and Nextdoor,” said Justin Raisner, an English teacher whose course includes publishing the site and a news magazine. Students are graded for their work, but he adds they tend to give more attention to their reporting assignments “because it still feels real and relevant.”

Whether they’re following district decisions over end-of-year grades, reporting on the latest health warnings or sharing first-person accounts of school closures, high school news teams haven't been stalled by COVID-19 from publishing timely articles for their audiences.

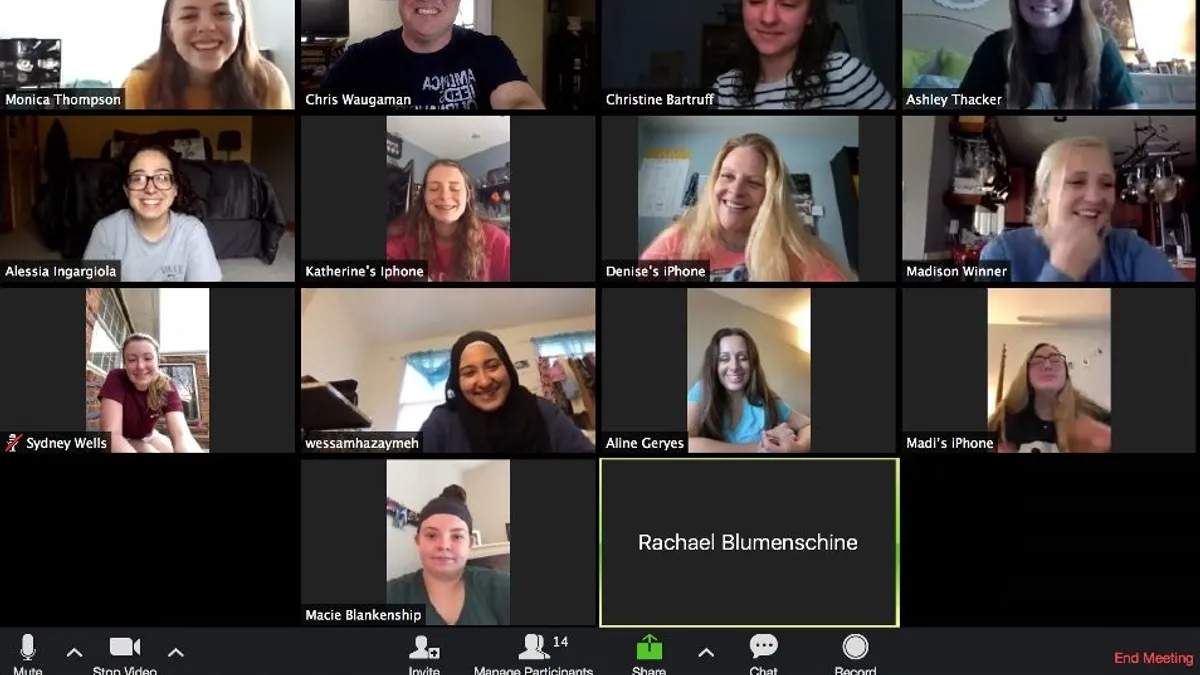

Already adept at using online publishing and design tools, many student reporters have made a smooth transition to remote work. “Our media team operates normally about 90% in the cloud,” said Chris Waugaman, an English and journalism teacher at Prince George High School in Virginia. And they’ve learned, he said, that “every day is a news day” with health and government officials regularly updating the press.

But editors and writers also recognize how the limitations of reporting remotely are affecting their coverage.

“Yes, you can talk on the phone with someone,” said Veronica Roseborough, a senior at Carlmont and the editor-in-chief of Scot Scoop news site. “But you can't really do justice to what they are saying if you are not there talking to them and witnessing their reactions.”

Coverage for the Scot Scoop team reflects broader patterns of how student journalists have positioned their reporting during the pandemic. Some are tracking cases of COVID-19 in their communities, following issues related to device and meal distribution and comparing district responses to the crisis — as PLD Lamplighter, the news site for Paul Laurence Dunbar High School in Lexington, Kentucky, did with the Fayette County and Jefferson County systems.

“Journalism students are among the nation’s most innovative problem-solvers, so they’re taking this in stride as they tell the important stories of their school communities,” said Sarah Nichols, president of the Journalism Education Association and a career and technical education teacher at Whitney High School in Rocklin, California.

“In many cases, the global health crisis has given them a renewed sense of purpose because they know their role documenting history matters more than ever — especially journalism students working on the yearbook.”

Nichols’ students had the opportunity to do on-site reporting when Whitney High had “a carefully coordinated cap and gown pick-up for seniors,” but for the most part, students are reporting by phone, email and social media. Audrey Boyce, a junior at Carlmont and a Scot Scoop editor, said she’s learned to be “more flexible and understanding that people may not be able to get the previously required three sources.”

Student news teams are also trying to provide some lighter material during this dark time, such as a Whitney Update article on "how to keep sane" and a feature on Italians singing from their balconies in Scot Scoop. Because they can’t cover sports or school activities, some of Raisner’s students have shifted to producing blogs and vlogs.

“I encouraged students to be creative and explore things they were interested in,” he said. “My hope was that this approach would allow students to get something positive out of the shelter-in-place orders.”

‘Restricted’ lines of communication

Earlier this month, the Society of Professional Journalists and the Journalism Education Association made a series of instructional videos on topics, such as ethics, headline writing and editing, available on YouTube. Part of SPJ’s #Press4Education program, development of the videos began in 2018, and they were filmed in 240 schools across the country.

But both students and teachers say the loss of a collaborative environment is what they miss most with schools being closed.

“The hardest thing about reporting from home has been not being able to meet with my editors [and] writers and get their opinion on my writing,” said Simakova. “The process for writing and publishing becomes a lot slower when our communication lines are restricted.”

And Sadie Bograd, a junior at Dunbar High and part of the news staff for PLD Lamplighter, said the incoming editorial board for next year isn’t receiving the usual “in-class mentorship from our current editors that they have in years past.”

Journalism teachers have the same frustrations.

“Face-to-face interaction is so valuable to the relationships on our staff, and the classroom is a second home to many of my students,” Nichols said, adding routines such as birthday celebrations, staff traditions and “popping” into the school newsroom during the day serve as a support system for students. “It's hard trying to develop alternatives to meet those needs and maintain the connectedness of our staff culture.”

‘The struggles of distance learning’

High school journalists are also likely in the best position to capture how their peers are adjusting to remote learning and longing to be reunited with their friends.

“One thing I think national media doesn't cover about students is that the majority of us … have started to lose interest in our schoolwork and hobbies,” said Simakova. “Many have stopped doing their homework completely because it no longer affects their grades. Others halted doing the things they love and are passionate about because they feel there's no purpose in doing them anymore.”

Waugaman agrees with grades closing out for the year, “high school students are still high school students, and many have found it difficult to be motivated to do work.”

To counter some of the “negative mental impact” lockdowns are having on teens, Boyce said staff members have been producing podcasts, videos, opinion articles and other content, ranging from at-home workouts to virtual cooking competitions, to help students feel connected to their peers,

“By highlighting the struggles of distant learning,” she said, “readers are comforted by feeling less alone during this time.”

Waugaman added some of his students have found “an inner strength to cope” and have learned focusing on work is one way to get through this time.

Other writers have chronicled how they’ve been personally affected by the outbreak.

“I laughed along with my friends when they shared memes or other jokes about the coronavirus on social media,” wrote Chinese student Max He in the PLD Lamplighter. “I brush it off and hide the fact that their jokes make me uncomfortable.”

Data on programs 'desperately needed'

As with students in general, the school closures have uncovered disparities in access to computers and reliable Wi-Fi at home, making it difficult for some students to conduct interviews over Zoom or use graphic design tools. At Prince George High, broadcast reporters who usually use Final Cut at school are improvising with iPhones and a teleprompter app, Waugaman said.

In California, Nichols agreed the socioeconomic differences among students are more pronounced now.

“A lot of my students are without adequate technology or reliable W-Fi, so they're automatically cut off from some of our interactions,” she said, “and that's requiring new solutions and another whole layer of flexibility.”

JEA doesn’t have demographic data on school journalism programs, although “it’s desperately needed,” Nichols said. But she added programs in lower-income communities are often in jeopardy or just don’t exist.

JEA’s Partner Project, which provides training for teachers launching new programs, and its Outreach Academy — an effort to promote diversity in school journalism — are two initiatives to “support underserved populations, but that’s just scratching the surface,” she said.

Students say they will continue to report on how the schools and their peers have been changed by the crisis, communicating details such as mask requirements at schools or what types of events will be allowed.

“Even after the pandemic is over, whenever that will be,” Boyce said, “we will likely still have many stories surrounding what a tremendous impact it has had — and will continue to have on the world.”