The novel coronavirus has forced school health staff to take temperatures, isolate and quarantine the sick, trace the contacts of the infected, and monitor the virus’ prevalence in schools. The pandemic also created another daunting scenario: the need to respond to alarming drops in students’ regularly scheduled immunizations, well-child health and dental check-ups, vision and hearing screenings and more.

“We believe a healthy child can learn better,” said Francis Luna, a school nurse at William H. Bradfield Elementary School in Garland, Texas, and the Texas director of the National Association of School Nurses.

A student population that’s updated on their shots can also protect the community from other preventable diseases such measles and whooping cough, said Laurie Combe, president of NASN.

According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, there were 44% fewer childhood health screenings between March and May 2020, compared to the same period in 2019 for beneficiaries of Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program. CMS data also shows a sharp 69% decline in children’s dental services.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports 34% fewer students had blood lead level testing between January and May 2020 than the same time period the year before.

School nurses K-12 Dive spoke to say these declines could have occurred for a variety of reasons, including families’ inabilities or concerns about visiting health care providers during a pandemic. They also say prolonged or sporadic school closures make it more difficult for school staff to monitor students’ physical and emotional well-being.

The CDC attributes the 20% to 70% decline of official reports to child protection agencies during the pandemic to the limited in-person contact between students and teachers, who are mandatory reporters of child abuse.

Combe said school nurses are currently filling a healthcare gap by connecting students and families with providers through telehealth and going directly to community locations to monitor children’s well-being and to educate families on the importance of preventative screenings.

Luna agrees: “The school nurse is the eyes and ears of the school population and the community. They address the physical, the mental, the emotional, just all the social health needs of the student.”

The student-practitioner-school connection

As they did before the pandemic, schools nurses are reviewing student health records to determine if children are up-to-date on their regularly scheduled vaccinations. Those age-based innoculation requirements are set by each state’s health department.

Despite the pandemic, several states are adhering to those health requirements in determining whether students can participate in face-to-face and virtual learning this school year. Some states, such as Pennsylvania, however, gave longer grace periods, acknowledging the pandemic-induced difficulties some families have faced in receiving routine, preventative medical services.

When school nurses notice lapses in students’ immunizations and preventive care, they work to connect families with community health care providers. But 25% of public schools in the country do not have a dedicated full-time or part-time nurse, according to NASN.

That means in schools without nurses, reviews of student health records for updated vaccinations may fall to an administrator, assistant or other staff who are not specifically trained in health services, Combe said. “I hope that this pandemic has illustrated the value that that health professional can bring to your school community, allowing teachers to teach rather than to care for ill students,” she said.

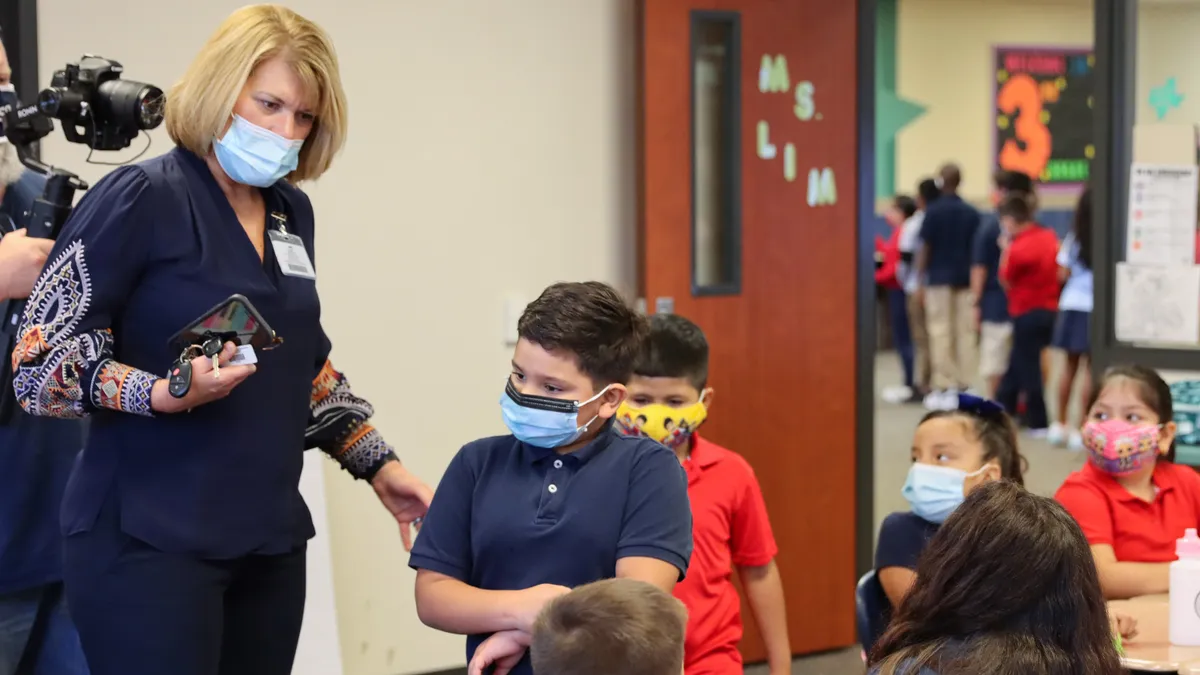

At Bradfield Elementary, where Luna works full-time as a nurse, the school is using telehealth to address minor health concerns and preventative care for students who are on campus. Through a partnership with Hazel Health Services, Luna can facilitate optional video conferencing between a student, the caregiver and a health practitioner. Hazel Heath Services provided the video conferencing equipment to the school as well as health monitoring equipment such as a blood pressure cuff, scale, pulse oximeter and more, Luna said.

One example of the efficiency of the partnership is when a student recently came to Luna because of irritation and redness on the hands. Through video conferencing, the remote health practitioner could see the student’s hands on camera and also asked the student several questions that led to the determination that the irritation was likely due to an overuse of hand sanitizer and lack of hand washing with soap and water. The recommendation: less sanitizer and more hand washing.

The nurse and the health practitioner followed-up with the caregiver and student to make sure the irritation decreased. The experience also led Luna to reignite an awareness campaign in her school about the need for staff and students to use soap and water to wash their hands in addition to hand sanitizer.

“I think it's a game-changer,” Luna said of telehealth. “It really assists a parent in leading the needs of the health of their child, especially during the pandemic.”

Bringing healthcare to students

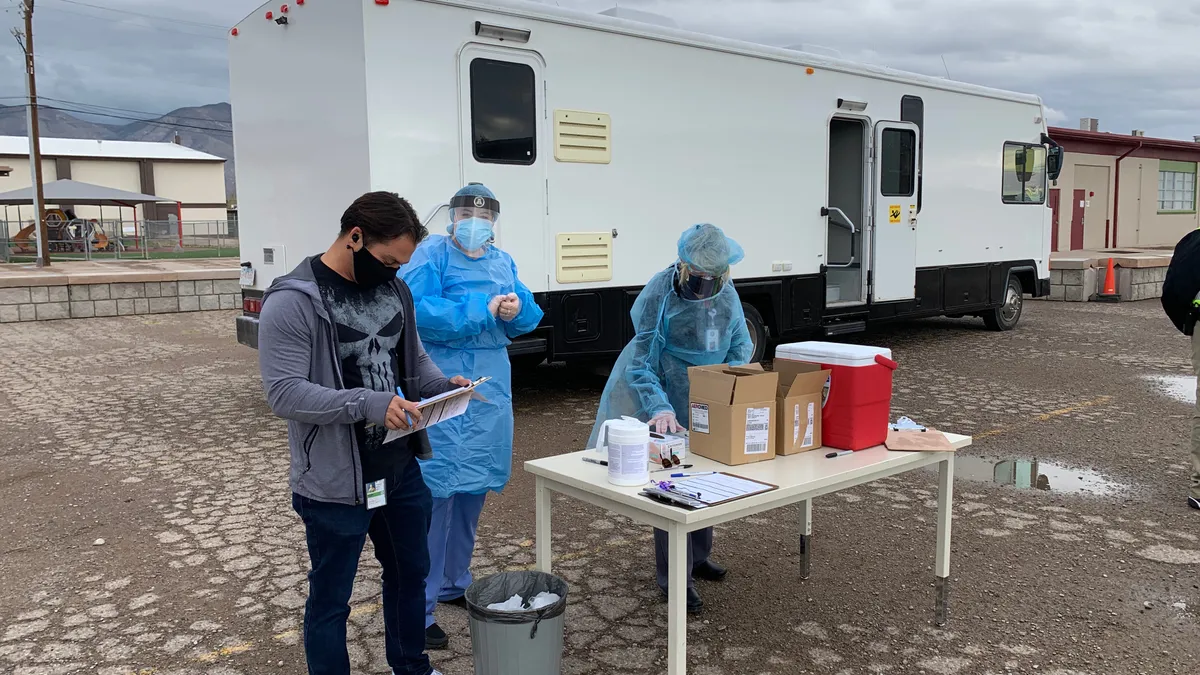

When the pandemic first emerged last spring, school nurses in Alamogordo Public Schools in New Mexico helped bring computers to students, educated school communities on COVID-19 mitigation, participated in virtual IEP meetings for students with disabilities, and set up virtual nurses' offices on school online platforms.

The district‘s nurses also have worked closely with the Otero County Health Department to support the department’s COVID-19 testing and vaccination efforts. But the nurses were eager to do more to care for students and the community, said Lisa Patch, the district’s director of health services.

So, when Patch heard a local Lions Club had an old Winnebago to sell, she thought it would be a good addition to the district’s efforts in COVID response and preventive care. The district purchased the 40-foot vehicle with CARES Act funding for under $10,000 and gave it some upgrades to make it roadworthy and ready for its healthcare mission, Patch said.

“We wanted the opportunity to get out into the neighborhoods and check on our families,” Patch said.

Since last fall, the motorhome, which the nurses call “Flo” after Florence Nightingale, has helped with the delivery of backpacks and school meals. In January, Flo was present at a community event where residents received healthy snacks and recipes, donated books, mental health wellness information, vision and hearing screenings and tests for COVID-19, Patch said.

The district has big plans for Flo, including dental screenings, distribution of a health education coloring book featuring the district’s mascots and a new, colorful outside design for the vehicle that reads, ”One community. Every child. Endless possibilities.”

“There's so many school nurses out there with great ideas, and I was just fortunate that my administration was open and willing to try something different,” Patch said.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards