Editor's Note: This is the second article in a package on innovative learning spaces. For the first, check out "The school that Khan built."

Meadowlark School, in Colorado’s Boulder Valley School District (BVSD), doesn’t have computer labs. The media center has been reimagined as a “curiosity center,” and even children in the early grades at this pre-K through 8th grade school rotate among teachers in different “learning studios,” depending on their academic needs.

Those are just a few of the design changes implemented this year at Meadowlark and three other BVSD schools with innovation funds made available as part of a successful 2014 bond issue.

Individual teacher desks have been replaced with a teacher collaboration space located within each “learning commons” and students are assigned to “huddle groups” that serve as a type of homeroom, giving parents a main point of contact even if instruction is provided by multiple teachers. In addition to large open rooms, meant to support group activities and project-based learning, there are also “cave-like” spaces for when students need to work alone, says Kiffany Lychock, BVSD’s director of educational innovations. “That’s the beauty of these buildings,” she says. “They’re flexible enough to change.”

Such innovative layouts and uses of space in schools are being seen across the country as district leaders strive to find designs that support the way students learn today and are flexible enough to accommodate how educators may decide to use them in the future.

“It’s a case of form should follow function, not the other way around,” says Julia Freeland Fisher, the director of education at the Clayton Christensen Institute, which has schools with innovative designs as part of its Blended Learning Universe network. “If you knock down all the walls, it needs to be anchored in an instructional model that dictates a potentially different use of space.”

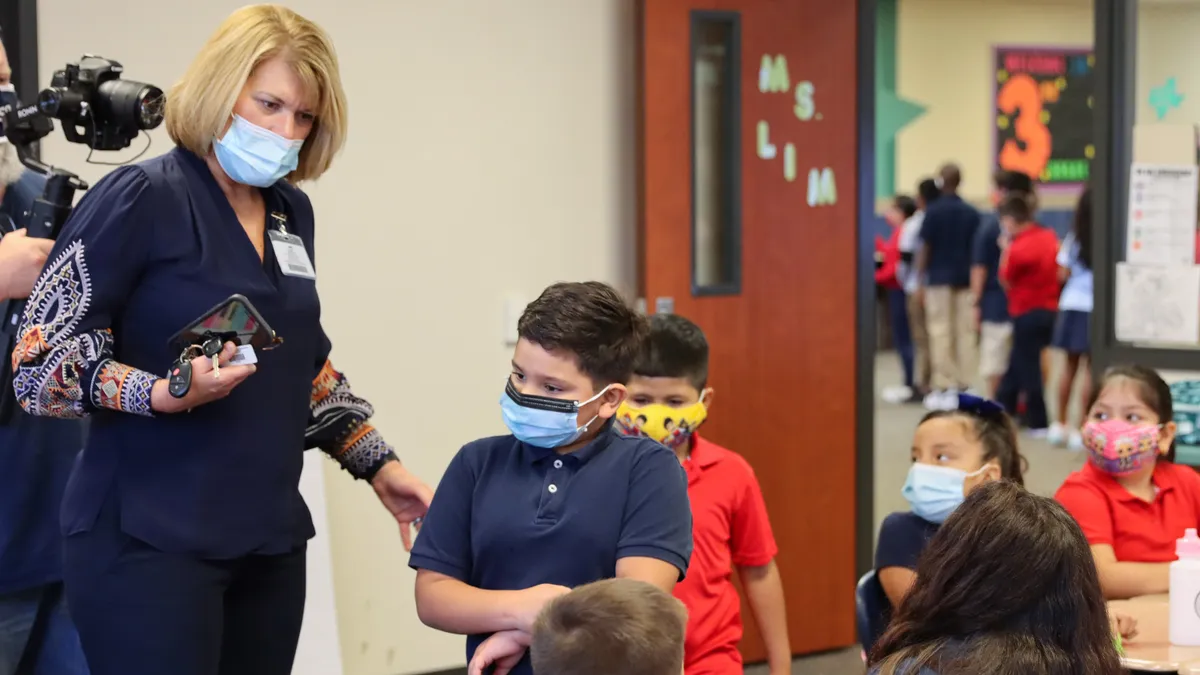

In Mentor (OH) Public Schools, east of Cleveland, that different use now includes a rotation model for grades 6-12, in which students separate into four or five groups and work on the skills where they need the most practice, based on assessments given the day before. Some students might be working online, others might be watching a video and in a third, a teacher might be re-teaching a concept.

“It’s a balanced approach,” says Mike Lynch, the director of Straight A initiatives, referring to a state-funded competitive grant program meant to encourage creative ideas for improving education. “There is a right time when a device can assist the student,” Lynch adds. “The idea is that not one lesson fits all.”

Schools and districts adopting these flexible approaches to design don’t believe that one type of seating fits all students either.

When students walk into a classroom at Mentor High School, they can choose between soft seating, stools or counter-height chairs. And even without a lot of funding or creatively renovated buildings, many educators are making adjustments to their own classroom spaces to better accommodate how students want to sit when they are listening, collaborating with a partner or working independently. “Wiggle” stools, for example, have become a solution in some classrooms for young children who have trouble sitting still for long periods of time. And 7th-grade English teacher Brooke Markle, who teaches at Mechanicsburg (PA) Middle School, found that simply reorganizing desks wasn’t giving students the space they wanted to complete their work. Sometimes they wanted to just “stretch out on the floor,” she writes in a piece for Edutopia.

She has also incorporated three different types of seating into her classroom — regular table height, standing options and floor seating, such as video game chairs and tires made comfortable with pillows. Parents even tried out the new seating arrangements at back-to-school night. To maintain some order, students are still expected to be in a “home base” seat for attendance, but are allowed to move around depending on what they’re doing.

“The shift in ownership has empowered students and has been the biggest impact I’ve seen this year,” she writes. “Students are taking more responsibility for their own learning as they see me model risk-taking in the classroom, and the flexible seating environment has played a large role in that shift.”

Testing out new ideas

Administrators leading schools with such flexible arrangements and reimagined rooms for learning recognize that they are testing out ideas — not all of which will be enthusiastically received. For example, because three of BVSD’s schools with the new design features were originally built as part of the 1970s era of open classrooms, Lychock says officials faced plenty of questions over whether they were just recycling an old idea. But the biggest difference between that concept and the designs being used today is the incorporation of technology, Larry Kearns, an architect involved the design of Intrinsic Schools in Chicago, said in an EdSurge interview.

“In a way, it is the antithesis of the 1970s movement,” he says, because while there might be one large space, there are specific areas within those spaces for different types of learning and interaction.

In addition, because design is constantly evolving, even the features being included in these schools might feel in a few years like having an iPhone 4 feels now. Fisher says, for example, that she knew of one school that went through an extensive redesign process, which included adding whiteboard walls. But then the school leaders wished they had made the desks with a whiteboard surface for students who might not always want to share their ideas with the whole class.

At Roots School, a K-3 charter school that opened in Denver in 2015, Executive Director Jon Hanover is hoping classroom design, combined with training for staff members, can create a personalized learning environment that provides a sense of safety and hope for children growing up in low-income, unsafe neighborhoods.

Large, open classrooms, each one called a “grove,” accommodate 100 students of mixed ages. Each grove is surrounded by smaller, breakout classrooms where teachers can not only pull students working at the same level, but even work with those that have the same gap in skills. “They can really tailor instruction to what kids need,” Hanover says.

After being open a couple years, however, leaders and teachers realized that students who had experienced the most trauma, had attachment issues, or had problems with self-regulation were struggling the most in a flexible space. So with additional funding, they “knocked down some walls and built some other ones,” to create a space in which students experience that independence more gradually. Kindergarten is now in a self-contained classroom with a partial wall that gives them some separation, while still connecting them to the rest of the “grove.”

Accompanying the physical changes to the space was a six- to eight-month process in which the faculty received training and visited therapeutic educational models so they could learn how to better support students’ social and emotional needs as they grow to a K-5.

While Hanover says it “would have been great” to have the foresight to build the partial wall initially, he added, that “no real innovation happens through just abstractly designing something in your head.”

Another challenge schools might face is that some teachers, even with modular furniture, will choose to line tables and chairs up in rows to resemble as close to possible a traditional classroom layout. “Rotation doesn’t work when you’re sitting,” Lynch says.

‘The intersection of ideas and information’

School libraries are also being affected by school redesigns. At Mentor High School, the media center is now a two-floor “hub” of the school, has a “college library feel” to it, Lynch says, and is in such constant use by students that the district is considering working with the local public library to extend the hours that it is open.

Meadowlarks’s “curiosity center” also includes a production studio and maker materials, but Lychock notes that makerspaces have been designed to be as mobile as possible to keep them from having the same fate that computer labs are having now.

At Burley Middle School, in the Albemarle (VA) County Public Schools, the pre-renovated library had an office, a closet and “an enormous circulation desk” that took up almost a third of the floor space, says IdaMae Craddock, the school’s library media specialist. Those spaces have now been “re-allocated” to the students for learning spaces and a recording studio. Students check their books out at two self-checkout kiosks and Craddock says she doesn’t need an office.

“I experience the library work areas in the same way that students do,” she says. “I know what's going on in the library and I'm that much more approachable to students and teachers.”

The flexibility of the space, for example, means that within one week, the library will be used for doing biology classifications, to host a mock press conference, and to run a “community expo night,” she adds. “Without the renovation, my space wouldn't be nearly flexible enough to do this kind of instruction back to back.”

With many large school districts no longer funding library positions, adapting library spaces to serve multiple purposes might concern some educators dedicated to library and media services. But Craddock doesn’t see replacing furniture as a sign that librarians are no longer important.

“The library is the intersection of ideas and information. I think when you stray from that intersection, then you have lost the core of the library,” she says. “I honestly can't imagine a book-less library, but books are not the only sources of information in the modern age. If you have a librarian who is excited about kids and learning and literacy in all its myriad colors, then the furniture is the least powerful thing about the library.”

Burley Middle’s 7th graders have likely been inspired by some of the library’s new features. They are actually participating in SchoolsNEXT, a design competition sponsored by the Association for Learning Environments. Winning entries from last year are not that far off from some of the configurations currently being implemented in schools.

'The right resource' at the right time

Proponents of these new designs, rotation models and smaller rooms for targeted instruction say they give teachers working in a blended learning model a chance to get to know students better. But another goal is to make collaboration and peer learning between teachers easier, eliminating the challenge of teachers attending a workshop on a particular practice or strategy, but then going back into their classrooms without a clear understanding of how to implement the methods on their own.

In the four BVSD schools with the new designs, teachers have common planning time every day in addition to being able to observe each other in the “learning commons.”

“It’s PD all day long,” Lychock says.

Craddock adds that in addition to providing better services to students, she is also more in touch with the units that teachers are getting ready to teach and can “forward the right resource right before the teacher needs it.”

In the Mentor Public Schools, part of the Straight A funds also went to creating Paradigm, a 16,000-square-foot professional learning center attached to the high school. The space includes an observation space so other teachers can view how their colleagues are implementing a blended learning lesson or instructional approach.

“It’s the space and the instructional strategies that work together,” Lynch says. “The space doesn’t matter; it’s the professional learning that goes along with the space that offers opportunities for teachers to try new things.”