Psychologists and researchers may be able to identify who is at risk for committing acts of school violence, but those assessments are still imprecise, L. Rowell Huesmann, a professor at the University of Michigan, told the Federal Commission on School Safety Thursday during a meeting focused on violence in the media, the role of video games and entertainment, and the impact of cyberbullying.

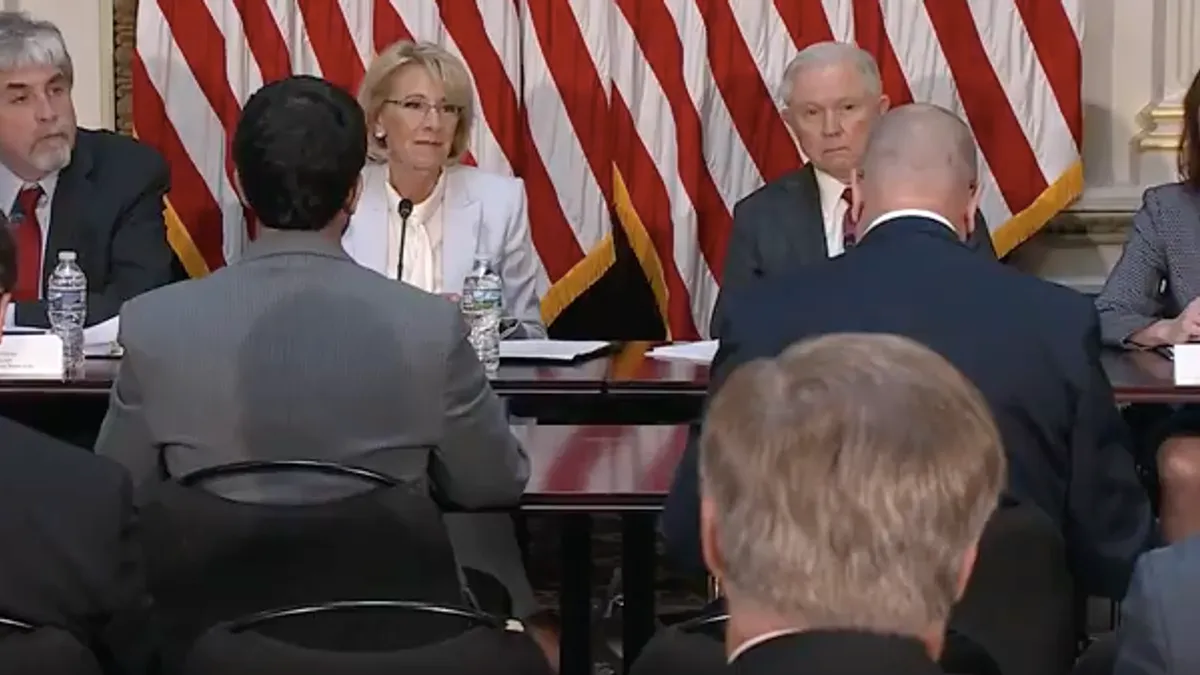

“We’re never going to be very good at predicting at a time who is going to shoot up a school,” Huesmann told U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, who chairs the commission, Attorney General Jeff Sessions, and representatives from the departments of Health and Human Services (HHS) and Homeland Security (DHS).

He added that screening students for mental health issues is not an effective prevention strategy, but that the more children and youth are exposed to violence — whether at home, in the community or in the media — the more “accepting” their brains become of using violence as a way to solve problems.

Noting that he and Huesmann often disagree on these issues, Christopher Ferguson, an associate psychology professor at Stetson University in DeLand, Fla., said that the notion that youth who play violent video games are more likely to become violent is not backed by research. The U.S. Supreme Court also agreed with then-Justice Antonin Scalia's writing in Brown vs. Entertainment Merchants Assn. that, “These studies have been rejected by every court to consider them, and with good reason.”

Ferguson added, “Our brains do seem to be efficient, even from fairly young ages, at distinguishing among reality and fiction.”

The session, which was live streamed on YouTube, also included Sioux City (Iowa) Community School District Superintendent Paul Gausman, who described his district’s efforts to prevent and respond to cyberbullying, including a Mentors in Violence Prevention program in which peers teach each other by creating “life-like scenarios.”

The district was featured nationally in the 2011 documentary “Bully,” which Gausman said opened the district up to criticism but also created a “meaningful conversation” about bullying and cyberbullying — not just in school, but in the community, as well. He said that while the district monitors students’ social media activity, he would like policymakers to give school leaders more authority to use students’ social media posts in their investigations of bullying.

Sameer Hinduja, a criminal justice professor at Florida Atlantic University and the co-director of the Cyberbullying Research Center, provided updated data showing that, among 5,700 middle and high school students, 34% report being cyberbullied and 12% report bullying someone else online. Creating positive school climates and positive norms around social media use can help reduce this form of bullying, he said.

“Schools must work to create a setting in which the responsible use of social media is just what we do around here,” he told the commission.

He added that many efforts within schools to address cyberbullying are random, “ad hoc and off-the-cuff,” and that student-led programs are likely to be more successful. “The last thing we want to do is waste time, effort and resources on adult-led initiatives that students know would never gain any traction," he said.

Are mass shootings contagious?

Jennifer Johnston, an assistant psychology professor at Western New Mexico University who has researched mass shootings, appeared to disagree with some of Huesmann’s comments by saying that mass shooters often don’t have a history of violence. But they both mentioned that mass shooters are narcissistic and want to see their faces and names in the press and on social media. That’s why she’s promoting a “Don’t Name Them” campaign, which she said could keep others from identifying with or wanting to emulate the shooter.

While entertainment violence, mental health identification and gun laws have remained fairly stable over the past several years, she said that “media contagion” has grown significantly. Studies, she said, show that widespread media coverage of one mass shooting means there is a 22% chance that another one will occur in a short amount of time, about two weeks. If there is a third and fourth shooting, she said there is a 100% chance there will be a fifth school shooting within a month.

Finally, Ben Fernandez, who chairs National Association of School Psychologists’ School Safety and Crisis Response Committee, said while he doesn’t want to censor the media’s coverage of school violence, he thinks they should balance the reporting with data on school safety and what schools are doing to help students cope with tragedies.

Additional funding for school violence prevention

The commission’s work has picked up in recent weeks, and in the opening comments, Sessions said the DOJ would be releasing another $25 million in grants to support school safety training through the Students, Teachers and Officers Preventing (STOP) School Violence Act — up from the $50 million originally appropriated. He announced that the FBI also plans to hold a school safety event next week.

Earlier this month, the commission held its first public listening session, where parents, students, members of advocacy groups and leaders of education organizations largely called for greater attention to students’ mental health needs and rejected the idea of arming teachers as a way to stop mass school shootings.

None of the four members of the commission — DeVos, Sessions, HHS Secretary Alex Azar and DHS Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen — attended that session.

In late May, DeVos and other representatives from the Department of Justice (DOJ), HHS and DHS visited a school in Hanover, Md., where experts and leaders of Anne Arundel County Public Schools discussed Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports — a widely used program for improving school climate.

And then in April, the commission held two closed "listening sessions" in which it heard from opponents and supporters of the Obama-era guidance related to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, which states that ED and DOJ will investigate complaints of discipline policies and practices that discriminate based on students' "personal characteristics.” DeVos has indicated she’s considering rescinding the guidance.

"Our job is not to mandate one-size-fits-all policies," she said Thursday, adding that leaders at the state and local levels are the ones who know "the unique needs of their schools and the resources of their communities."