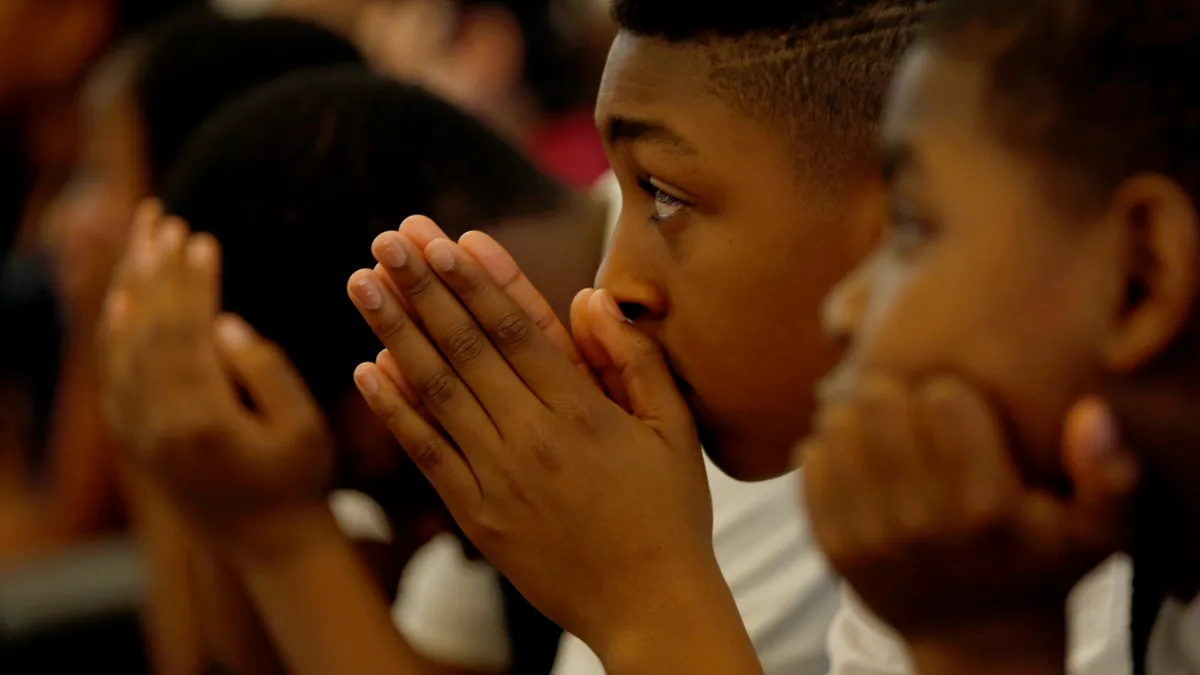

The number of K-12 students identified as being homeless during the 2013-14 school year was double the number identified in 2006-07. While a portion of that increase can be attributed to better identification and tracking by schools, the last recession also forced more families out of their homes, and recovery has been slow.

Even still, the 1.3 million homeless students — disproportionately minorities — identified during the 2013-14 school year is expected to be the low end. Sometimes students and families intentionally hide their circumstances, whether it is because they fear being separated or forced back into unsafe conditions.

At the college level, the infrastructure does not exist to shine a light on even a portion of the homeless student population. While a coordinated network of support targets homeless youth in elementary and secondary schools, thanks to the McKinney-Vento Act of 1987, requirements of colleges and universities basically do not exist. Homeless students qualify as independents for financial aid considerations on the FAFSA, and while the federal TRIO programs include some provisions for homeless and foster youth, colleges and universities are not required to do anything to identify or support these students. Because of this, most colleges do not even know the scale of the problem on their campuses.

Barbara Duffield, director of policy and programs at the National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth, said there is growing awareness of homelessness in higher education. But she adds that some people still have the perception that, while kids may struggle in college, they can’t possibly be homeless — because wouldn’t homeless students be focused on survival, not higher education?

Not quite.

“Kids know higher education is the way out of their situation,” Duffield said. “They’re trying to get the degree knowing that’s the way out.”

NAEHCY is among the organizations advocating for more accountability in the post-secondary realm. Sen. Patty Murray (D-WA) has introduced a bill that would require higher education institutions to designate a single point of contact for homeless youth. The Georgia Board of Regents has already mandated this on every campus — a best practice that so far has remained an exception throughout the country.

At the K-12 level, the McKinney-Vento Act requires homeless student liaisons in every district. These liaisons are supposed to make sure homeless students are aware of their rights and they help coordinate services. The federal law comes with funding to help districts meet their obligations, but as the homeless student population has grown, federal funding largely has not.

Barbara Dexter is a McKinney-Vento liaison with the Anchorage School District in Alaska. She is one of the few who works full-time in this role, rather than splitting responsibilities with other administrative duties. According to data from the recently released "Hidden in Plain Sight: Homeless Students in America’s Public Schools" report, 89% of liaisons say they spend half of their time or less on their duties to homeless students. Dexter, however, has been lucky to count on a string of supportive superintendents over her 23 years in the district.

Dexter’s caseload is about 1,400 kids and her office of five serves 4,000 across the 50,000-student district. She connects with homeless students through referrals from local shelters, which send daily lists of everyone who spent the night there, as well as teachers and counselors. Sometimes students call her directly because they have heard of her from their peers.

Dexter helps students and families find shelters, coordinate transportation to and from school, fill out forms for public assistance, locate food pantries, and for older students, think about college. She figures out the barriers keeping students from full academic participation and works to remove them.

“My real focus is getting kids toward graduation,” Dexter said. “I’m an educator first.”

The job has become more challenging, though. In the 1990s, Anchorage had more space in public housing. At that time, a family could go into a shelter and six weeks later be in a new home, Dexter says, but now it could be years before they find a stable place to live. There are students in the district who have been homeless since preschool — their entire school careers. And right now, Dexter sees once-middle-class families navigating homelessness for the first time. These families struggle in an unfamiliar situation and are more prone to hide their situation.

Another challenging population to serve are unaccompanied youth who do not have their parents to rely on. Fully half of Dexter’s caseload is made up of unaccompanied students and half of liaisons surveyed for the "Hidden in Plain Sight" report say this type of student presents a “major challenge” when it comes to connecting them with services and supports they need.

Lead author Erin Ingram recommends schools standardize the process of identifying homeless students and offer more training to teachers and counselors, beyond just McKinney-Vento liaisons.

“Families don’t tend to become homeless on a school schedule,” Ingram said. “If you only check for that in the beginning of the year, you may not have another point of contact until the end of spring or beginning of summer.”

The latest version of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act made a handful of updates to the McKinney-Vento Act that will take effect Oct. 1. High school counselors will have to prepare and advise homeless youth about college and McKinney-Vento liaisons will be obligated to inform homeless students about their status as independents when it comes to federal financial aid for college. Schools will also have to report on the outcomes for homeless students as a subgroup and track their progress.

With the Higher Education Act due for reauthorization, advocates hope the needs of homeless students will make it into new regulations for colleges and universities, too.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards