Fewer than half of states seem to be well-placed to ensure successful implementation of college- and career-ready standards. That’s according to a new analysis from C-SAIL, the Center on Standards, Alignment, Instruction and Learning at the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education.

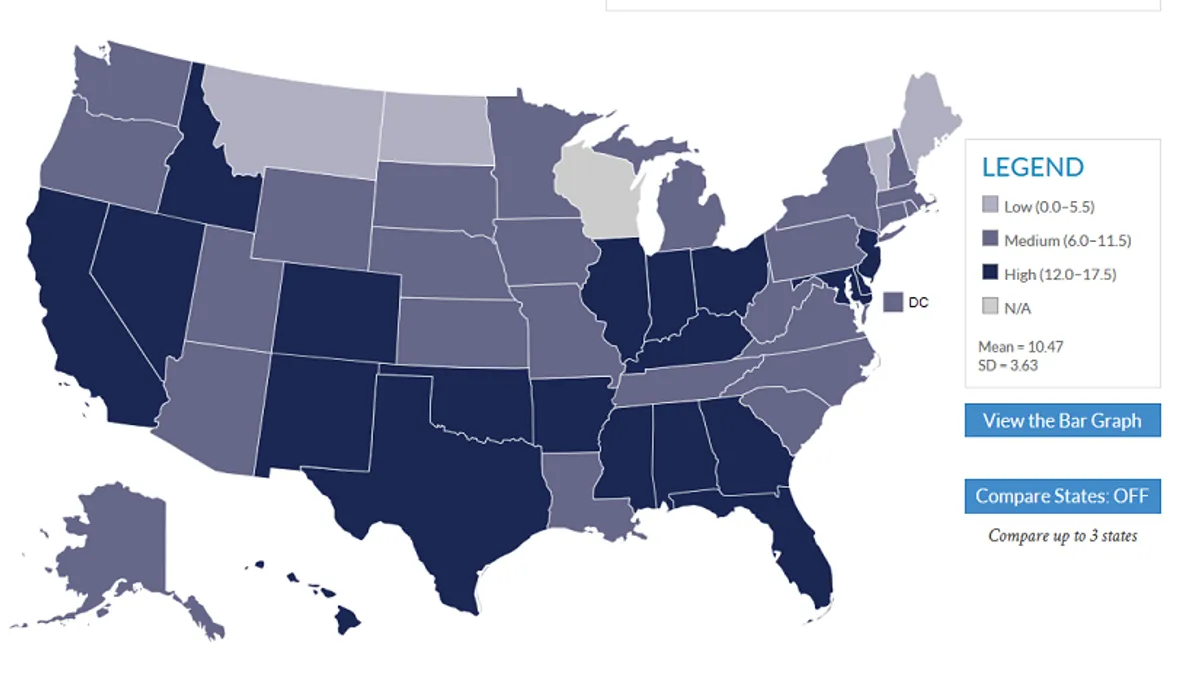

Researchers examined each state’s college- and career-readiness policies as well as their related reform initiatives and assessed them across five policy attributes C-SAIL Director Andy Porter has posited are necessary for successful implementation — specificity, consistency, authority, power and stability. Only 20 states ranked high overall and Maine, Montana, North Dakota and Vermont all received low overall scores. The rest of the states fall somewhere in the middle, though Wisconsin asked C-SAIL not to publish its state data.

Porter’s policy attributes theory hinges on what, exactly, states have to do to develop policies that can have an impact in schools. He said when it comes to college- and career-readiness, states have plenty of room for improvement.

“It’s all about implementation,” Porter said. “What can states do to get these standards implemented? If they’re not implemented, they’re not relevant.”

College- and career-readiness has been a driving force behind educational standards for years now, but the standards themselves have to actually reach all the way down to classrooms to impact instruction.

Specificity and consistency

At this point, 15 states have yet to release a public definition of college- and career-readiness, creating an ambiguous end goal for how schools should be preparing students. And nearly half of states do not explicitly require students to take high school courses that are aligned to college- and career-readiness standards for graduation.

Stability

Looking at a 10-year period, Katie Pak, a doctoral student at the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education and lead researcher on the maps project, found relatively low levels of stability in state policy toward college- and career-readiness, attributing those levels to the backlash against the Common Core State Standards initiative.

In a blog post describing her key findings, she wrote that just in 2016, “The highly politicized nature of the Common Core has caused legislators to introduce 35 bills to repeal the current standards, 26 to repeal the current assessment system, 62 to modify the assessment (10 of which have been enacted), 67 to delay the implementation of or use of student achievement scores in state accountability systems (6 of which have been enacted), and 56 to modify the state accountability system (10 of which have been enacted).”

Authority and power

Only Texas, Hawaii and Arkansas scored high on “authority,” assessed based on whether states have passed recent legislation, rules, regulations or executive orders that support college- and career-readiness efforts, whether high school students are required to take assessments that determine college- and career-readiness, and whether states require school districts to offer an intervention to students who score below their college-readiness benchmark on state tests.

The strong tradition of local control when it comes to education has limited support for directives from the legislature and governor’s office.

Slightly more states — 9 — scored high when it came to power, which in this context is defined by Pak as whether states include college- and career-readiness in their school accountability system and whether there are specific rewards or sanctions tied to those ratings.

But Porter said between authority and power, authority creates a more lasting commitment to a given policy. States that exercise power under the C-SAIL definition get compliance because of carrots and sticks. More difficult is to persuade stakeholders that a given policy is a best practice, worth doing whether or not it is enforced.

Looking ahead

The messy rollout of the Common Core State Standards created fierce proponents and opponents, even though too few people on either side of the debate have actually read the standards themselves. Porter said few teachers he works with through C-SAIL have truly engaged with the standards or come to a clear understanding of what they are and are not.

“The big challenge is to get these standards understood sufficiently well so they can be incorporated into instruction in ways that students benefit from,” Porter said.

Writing standards is the easy part. Faithfully implementing them is difficult and expensive. And that is the work worth monitoring as states operate under the Every Student Succeeds Act to structure their state policy around education.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards