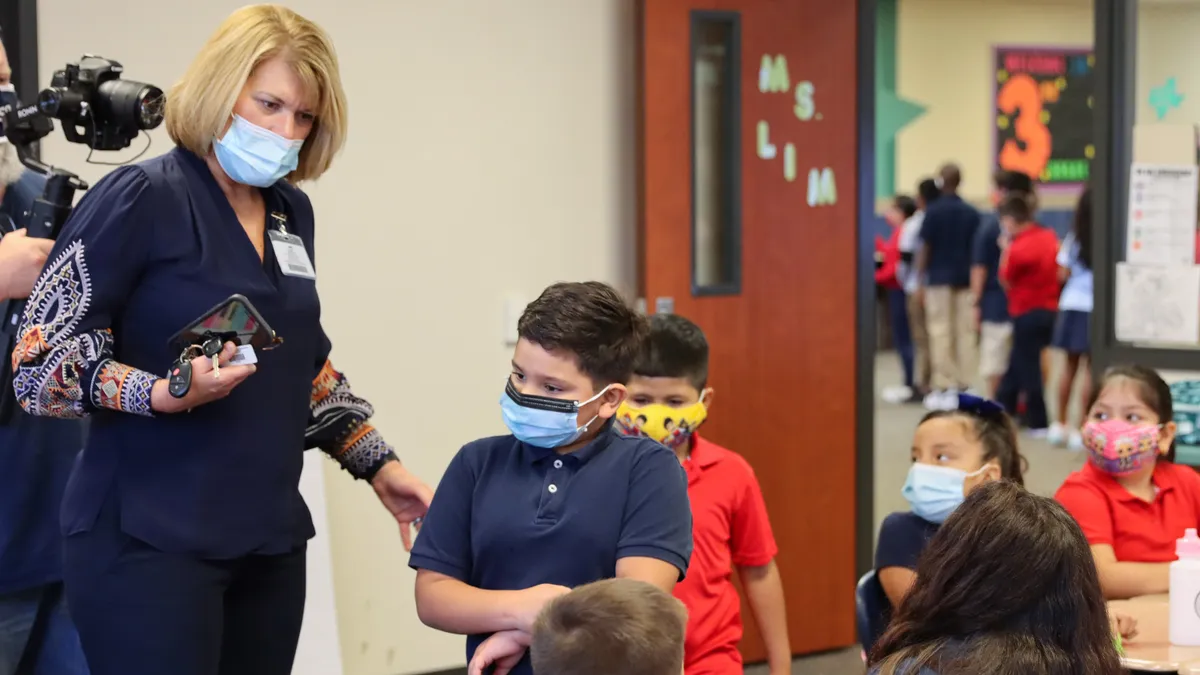

The 5,600-student Ridley School District in Folsom, Pennsylvania, is not immune to the ongoing and worsening substitute teacher shortage nationwide.

“I think this month is probably going to be our toughest month as we look at the number of [teacher] absences,” said Ridley Superintendent Lee Ann Wentzel. “Right now with the quarantining, the isolation — that’s compounded the issues.”

On Friday, for example, Wentzel said the district had eight teacher absences left unfilled by substitute teachers.

Since schools nationwide have returned from winter break, the omicron variant and ongoing school staffing shortages have significantly impacted some districts’ abilities to continue in-person learning.

“This is not just going to be a short-term issue. We saw this coming, and as our profession has taken some hits out in the public … schools of education had significant declines in enrollment at the higher ed level,” Wentzel said, referring to strains on the teacher pipeline even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. “So our pool was already thin going into this, and that’s sad on a number of fronts. You want people who want to be in this profession and want to pursue it.”

A new report from the Illinois Association of Regional Superintendents of Schools found 96% of 663 districts surveyed facing a substitute teacher shortage, while 88% said they have a teacher shortage problem.

Respondents reported hundreds of classes being canceled or converted to online instruction because of this situation. On top of that, 90% of districts said the substitute shortage in particular is just getting worse.

But in Pennsylvania, Wentzel remains hopeful about Ridley and other districts’ ability to successfully address hesitancy to enter in the education profession that is affecting shortages of both regular and substitute teachers.

States loosen requirements

In recent months, states have increasingly passed legislation and executive orders to help ease the shrinking labor supply of substitutes, including in Pennsylvania, where Gov. Tom Wolf signed a bill Dec. 17 expanding the pool of eligible substitutes. The law extends this flexibility through the 2022-23 school year, permitting retired teachers, eligible college students and recent education program graduates to all serve as substitute teachers.

In Michigan, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer Dec. 27 signed a law that also expands eligibility for who can be a substitute. The new Michigan law allows any staff member already working at a school, such as secretaries and paraprofessionals, to substitute teach this school year even if they are not certified.

Even more recently, the Kansas State Board of Education Jan. 12 approved an emergency declaration lifting a requirement through June 1 that substitute teachers have at least 60 semester credit hours from a regionally accredited college or university to obtain an emergency substitute license. For now, substitutes only need a high school diploma and must be at least 18 years old, have a verified employment commitment from a district and pass a background check.

The media attention sparked by the Pennsylvania law has helped generate interest in substitute teaching for Ridley, Wentzel said. She anticipates these conversations at the state level to possibly reignite an overall interest for working in education.

“Hopefully, this is going to inspire some people to enter back into that field of education and want to take part, because, for me, this isn’t just an occupation,” she said.

‘Really detrimental, cascading effects’

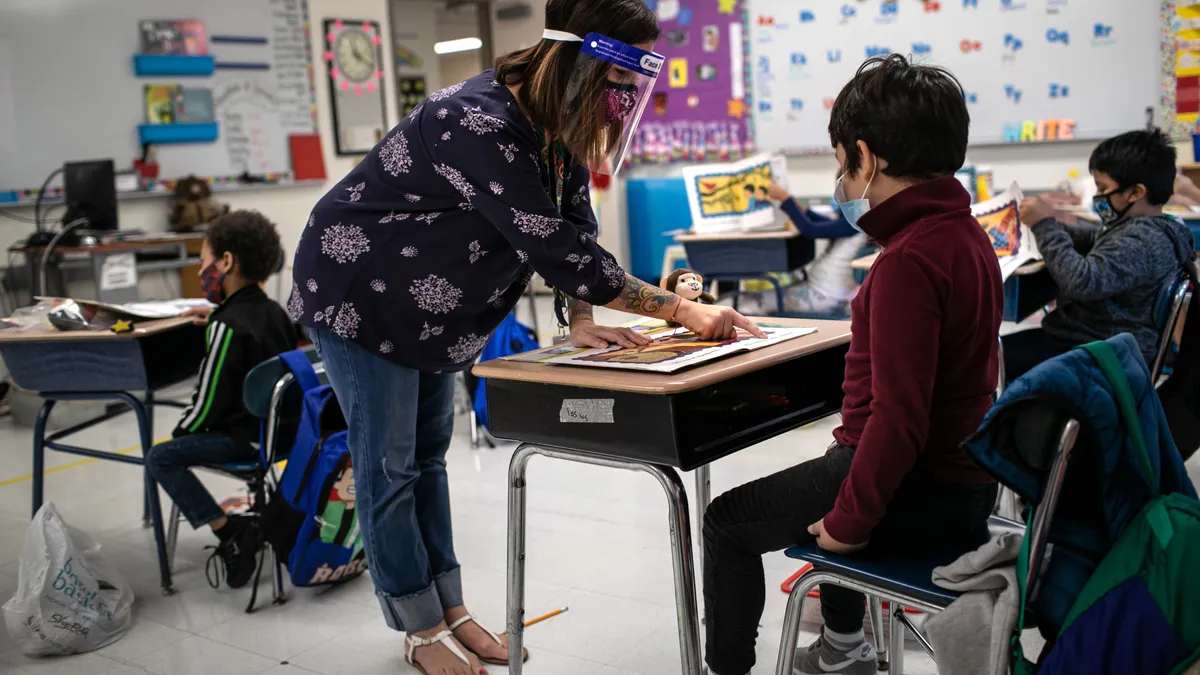

Loosening substitute requirements makes it easier to recruit people to fill in for teachers, which helps prevent burnout by allowing teachers to take time off as needed, said Jing Liu, an assistant professor in education policy at the University of Maryland College Park.

When schools don’t have enough substitute teachers, students, school culture, and staff morale are all hurt, said Matthew Kraft, an associate professor of education and economics at Brown University.

“That can cause really detrimental, cascading effects on not just the kids, whose teacher is absent and who the school can’t find a sub to fill in for, but for other students in the building, other teachers in the building,” Kraft said. “Why? Because when schools can’t find a sub, that means they have to pull an adult from other duties.”

While an overall substitute shortage is a problem for schools nationwide, there is also an unequal distribution of substitute teachers among schools, Liu said.

Schools with high poverty rates, low achievement levels, and higher proportions of Black and Hispanic students were less likely to find substitute coverage compared to more affluent, higher-achieving schools with a higher proportion of White students, according to a 2020 study co-authored by Liu.

Also, a universal reason substitute teachers avoid certain schools is student behavior, Liu’s study found.

“They can be easily overwhelmed by student behavior,” he said. “That’s something we need to consider to overall improve working conditions for sub teachers.”

Liu said it’s easier to address the unequal distribution of substitute teachers by offering higher pay for districts with more substitute vacancies than it is to find solutions to the nationwide shortage as a whole.

Building momentum on current solutions

Districts struggle to fix the substitute teacher shortage due to a lack of appeal for the positions. Substitutes don’t get full-time benefits, nor is there a clear career trajectory, Liu said. Plus, there’s competition from other industries for temporary work, including ones that are less demanding than teaching, he said.

At Ridley, Wentzel said the district is unique in that it does not use an outside service to find and hire substitutes. The district actively recruits using its own sub list, which has the benefit of building meaningful and personal relationships between substitute teachers and schools, she said.

While not every substitute becomes a full-time teacher, Wentzel said the district views the temporary position as an on-the-job interview opportunity. The district also tends to recruit by reaching out to local high school graduates, Wentzel said.

Ridley has chosen not to try to financially compete against neighboring districts when recruiting substitutes, she added. Most of Ridley’s subs earn $100 per day, although those who consistently report to the same school, known as building subs, make $125 per day, Wentzel said.

To continue addressing the immediate need for substitute teachers, Kraft said raising pay is key for most districts, as is lowering the bar for hiring to at least an associate’s degree. For the long term, Kraft said districts should consider using federal American Rescue Plan stimulus funding to build out full-time substitute labor pools in their communities.

While Kraft is optimistic about districts creating a local pipeline of high school graduates into substitute positions and eventually full-time teaching, he said there’s not enough evidence to support the effectiveness of those programs yet.

Liu had a few practical ideas he said can go a long way to improve a substitute teacher’s experience. For instance, schools can ensure subs have a parking space at the school. It also helps to provide a lesson plan or train substitutes on a classroom management system ahead of time, he said.

If schools hold high standards for teachers to better support and prepare subs, they will more likely return when teachers need time off again, Kraft said.

He added subs should “feel like they’re not left on an island, but that they are a part of a larger community rather than just being kind of a stand-in."

Dive Awards

Dive Awards