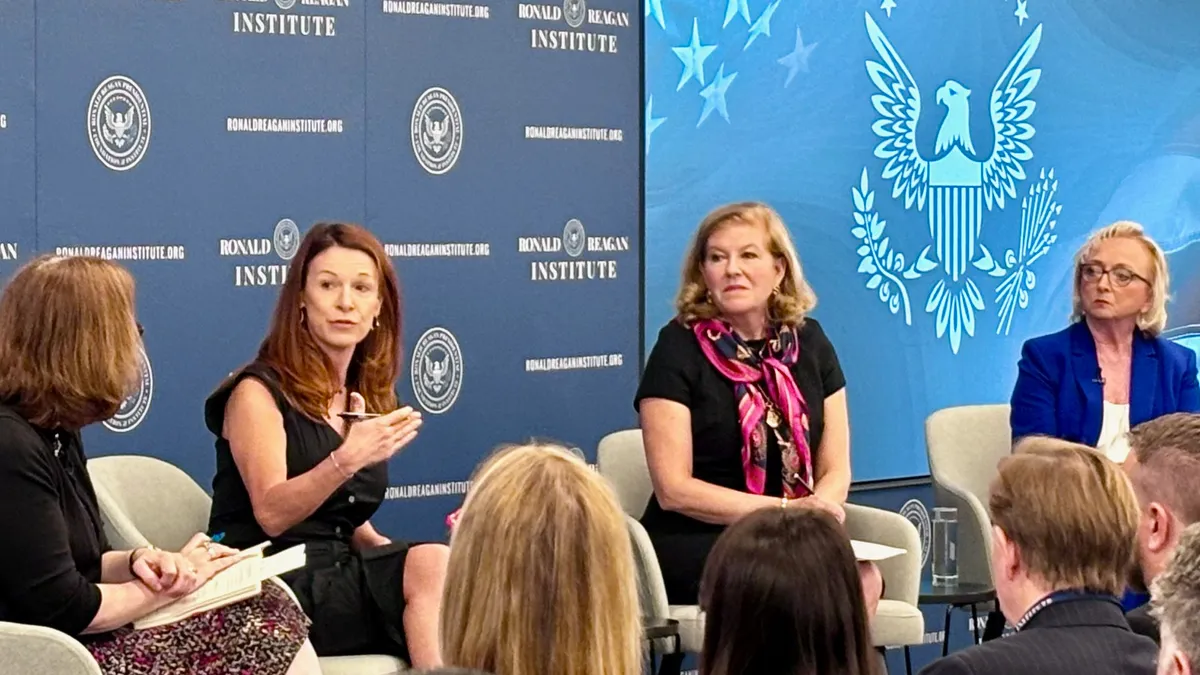

WASHINGTON — The K-12 education system is putting more rigor into accountability systems after years of lowered expectations — and while there's a lot of opportunity for innovation, it is a process that takes time and commitment, said state education leaders speaking Thursday during a panel at the Reagan Institute Summit on Education.

The speakers emphasized that there's not a one-size-fits-all approach to accountability, and that the components for performance standards — such as graduation rates, literacy proficiency or Advanced Placement course participation — may differ from state to state based on student outcomes and as determined by each state's constituents, families and educators.

Carey Wright, Maryland's state superintendent of schools and former Mississippi state superintendent from 2013-2022, told attendees that years ago when Mississippi sought to improve student outcomes, it took a close look at assessment and other data to find where adjustments were needed.

Leaders discovered that the statewide assessment was not accurately measuring proficiency, and that its assessment and accountability systems were weak, Wright said. Mississippi also sought to make improvements to the lowest-performing schools. Over the last decade, the state has made strong growth in student assessment scores.

Wright said Maryland is now in the process of reviewing its accountability and assessment model.

"What are we really holding schools accountable for?" Wright said, adding that the answer to that question is what leaders need to build into an accountability model.

The speakers pointed to common elements of strong accountability systems:

- Transparency of student and school performance levels.

- Analysis of performance data for targeted interventions.

- Stakeholder input, including from teachers and parents.

- A laser focus from state, local and school officials on student outcomes.

Flashlight, not hammer

Kirsten Baesler has been North Dakota's elected state superintendent since 2012. She said that there's been pressure over the years — and now — to ease the focus on standardized test scores.

"I think there's a lot of pressure on state leaders, on state education leaders, to roll back the assessment piece of our accountability to measure other things, and I just, I can't do that in North Dakota," she said, adding that other state education leaders are in agreement.

Meanwhile, North Dakota has added elements to its accountability framework, including a Choice Ready initiative that monitors student readiness upon high school graduation. The measurement includes academic growth and gains, as well as specific indicators of school success for preparing graduates in three areas: post-secondary education, workforce and military readiness.

When the state gathered baseline data in 2017, it found that of the 90% of students graduating high school, only 23% were considered Choice Ready, Baesler said.

Resources were reallocated toward this effort, and high schools were measured by those outcomes. Last year, 70% of graduates were deemed Choice Ready, Baesler said.

"What this accountability did was shine a light on it," Baesler said. School districts and teachers are now working hard to improve outcomes, but that process takes time, she said.

"I'd say there's educational malpractice if we believe our students cannot achieve," Baesler said.

Aimee Guidera, Virginia's secretary of education, said data is key for accountability and uncovering where improvements are needed. "Use every piece of data we can that's going to help identify where every child is," she said, adding that the data can be used to support each child.

Making assessment and other accountability data transparent is not a "gotcha" moment, she said.

"This data should be used as a flashlight, not a hammer," to help guide improvements and interventions, Guidera said.