Dive Brief:

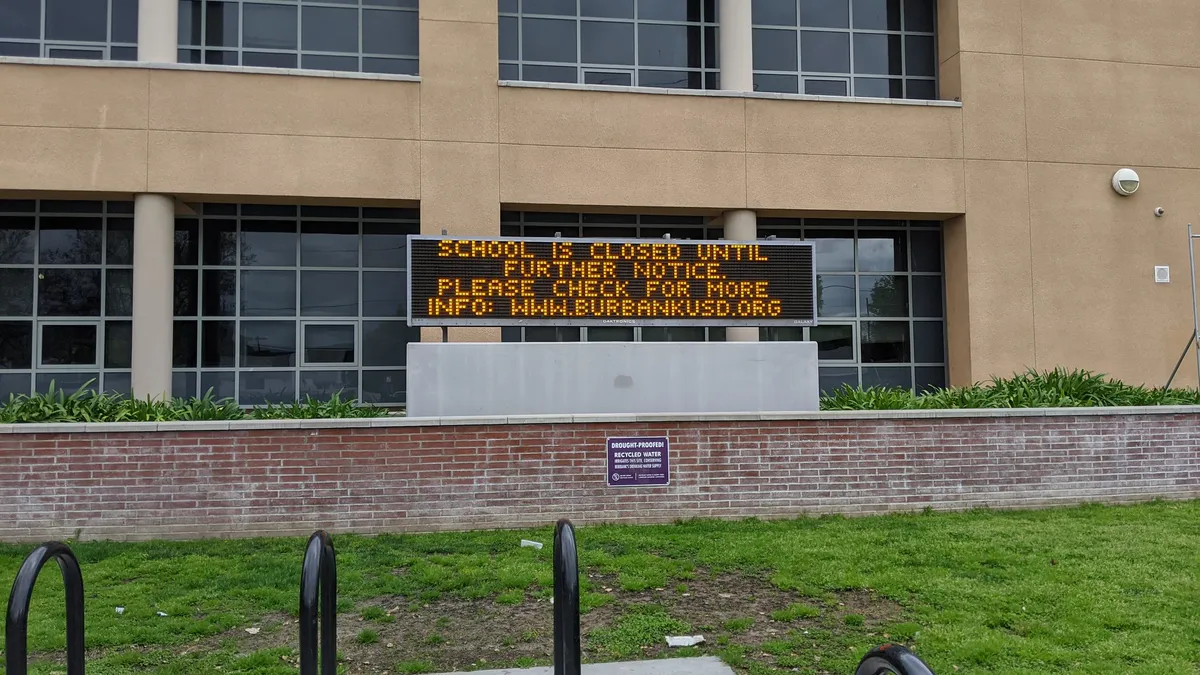

- Despite school closures in 2009 over swine flu, most districts didn’t prepare for a pandemic that would shutter schools for months and require large-scale distance learning, with research from Child Trends released in March showing only eight states had guidance for distance learning during pandemics, The 74 reports.

- While all states except New Hampshire had requirements outlining how schools should respond to a disease outbreak, many states didn’t require leaders to plan details like remote instruction, food service or emergency planning.

- In a 2016 report, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found 70% of districts had infectious disease outbreak protocols in place, but only half detailed how to continue operations and resume classes if schools closed for an extended period. A 2012 survey of 2,000 school nurses in 26 states showed less than half said their districts updated emergency plans after that outbreak.

Dive Insight:

Before the coronavirus pandemic struck, the U.S. Department of Education's Readiness and Emergency Management for Schools fact sheet advised that districts should have plans in place to recover academically, physically and structurally, and socially and emotionally, as well as a way to recover business operations. As part of the social-emotional recovery, for example, it recommends districts provide "Psychological First Aid" and conduct ongoing assessment and monitoring of student, teacher and staff mental health.

Last September, an emergency planning guide was also jointly released by the Departments of Education, Justice, Homeland Security, and Health and Human Services to aid districts in planning for and recovering from emergency situations. It instructs districts to work with community partners to plan for all types of hazards, from natural disasters to gun violence. The guide mostly focused on emergency planning to respond to and prevent violence in school.

Though the H1N1 flu did not cause the type of widespread closures triggered by COVID-19, it should have been a "wake-up call," according to Thomas Chandler, a research scientist at Columbia University’s National Center for Disaster Preparedness. Epidemiologists and researchers were aware an outbreak like COVID-19 was possible.

During the 2009 swine flu, the U.S. Department of Education recommended districts use websites to share information with staff, students and families in the event schools had to close. The department also said schools should use radio, public broadcast television stations, telephone conference calls, phone tutoring and educational packets to support students.

Ed tech was not as widely adopted then as it is now. Following the H1N1 outbreak, schools adopted more 1:1 devices. Platforms like Zoom have also been developed.

But while many districts have the technology to transfer students online, some students still lack internet access at home. As schools plan for continuing closures, districts should focus on creating equitable access to all students. Districts have partnered with local wireless services to provide families internet service at a lower cost, invested in hotspots, and sent home packets where even hotspots wouldn't work.

In early March, the majority of districts prepared for approximately two weeks of paper packet materials, according to the AASA, The School Superintendents Association, since the CDC's recommended quarantine time was 14 days. Many districts provided meals through grab-and-go lunch stations, and some districts delivered meals on buses.