Lessons In Leadership is an ongoing series in which K-12 principals and superintendents share their best practices as well as challenges overcome. For more installments, click here.

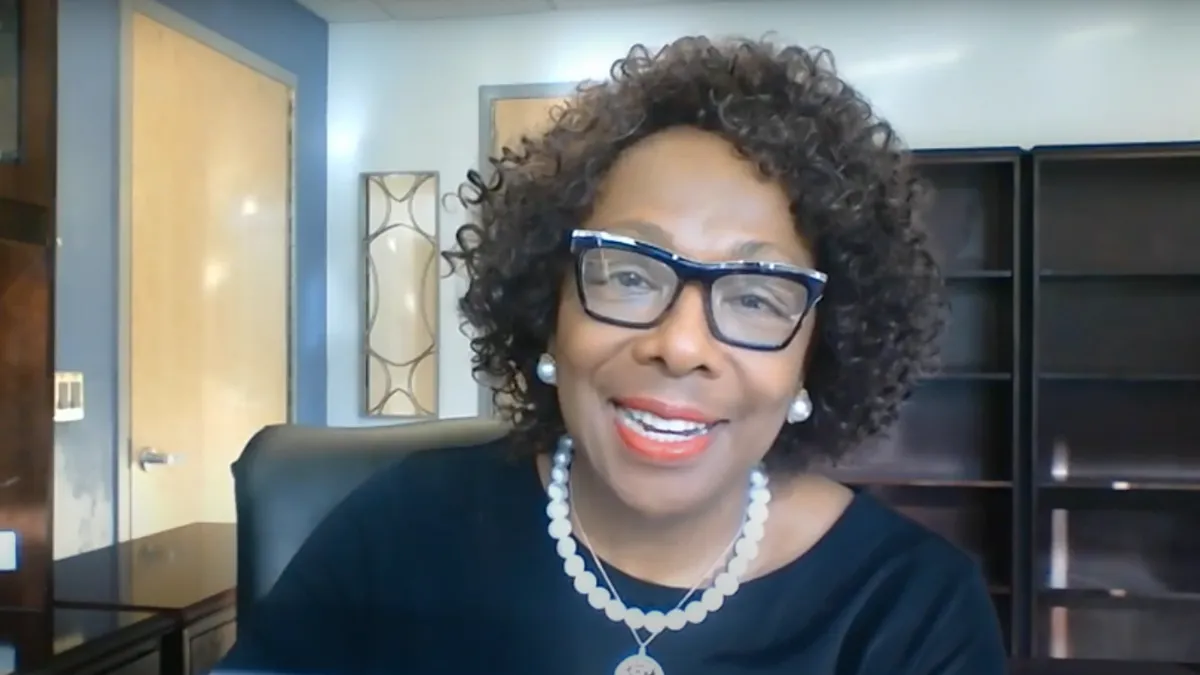

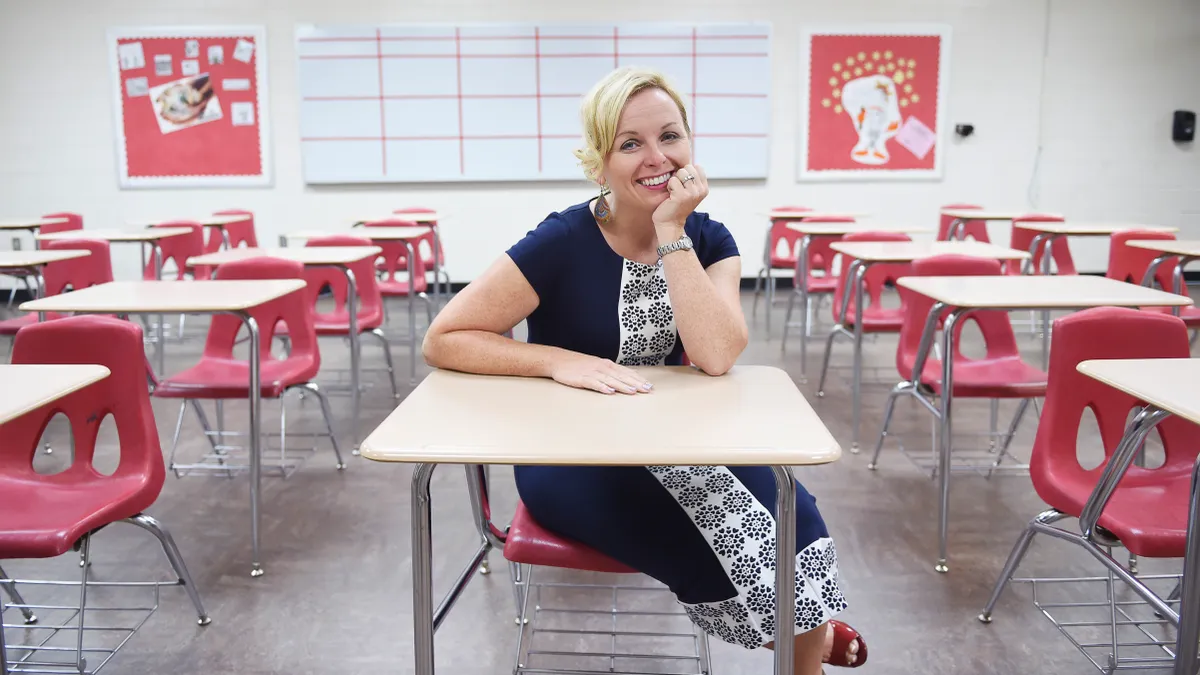

When Sue Mariani took the reins of Pennsylvania’s Duquesne City School District in 2018, her two decades of experience in education had already included wearing a number of hats in another Pennsylvania system that was in receivership, York City School District.

In 2007, a combination of financial mismanagement and lack of academic offerings and proficiency led the Pennsylvania Department of Education to take grades 9-12 from Duquesne, sending those students instead to nearby districts. Grades 7 and 8 were pulled from the district in 2012 following cuts to basic education funding.

Since arriving, Mariani’s primary goal has been clear: Bring the secondary grades back to the district. But doing so in a way that’s innovative, sustainable and in line with accountability goals in a district under receivership — and where 88.5% of students get free or reduced-price school meals — is easier said than done.

We recently caught up with Mariani to learn more about what went into bringing back grades 7 and 8, where she’s at on restoring high school grades to the district, and how student voice and community engagement have factored into the success of these efforts so far.

Editor’s Note: The following interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

K-12 DIVE: Duquesne was a K-6 district when you took over, and one of your first moves was to restore middle school grades. What work went into that? How does it play into the overall plan for recovery for the district?

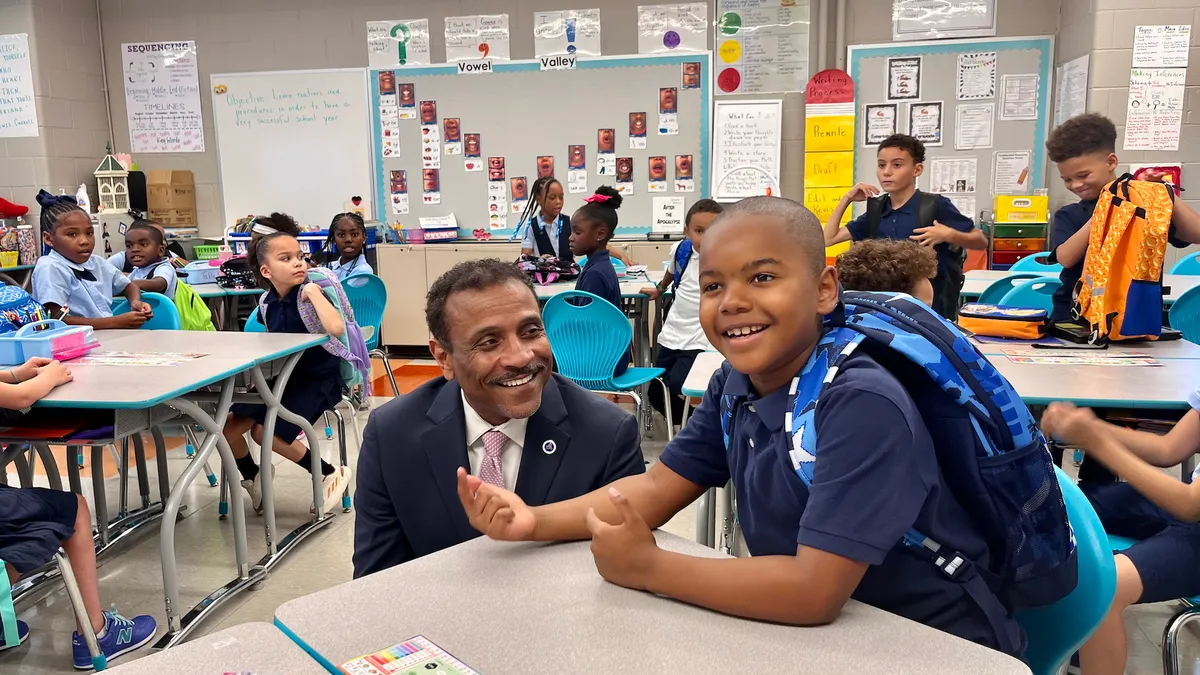

SUE MARIANI: One of the first things I did when I got here — most like every other superintendent I've ever come across or worked with — is I had a bunch of meetings with different stakeholders. Basically, my marching orders were “restore our school district.”

I just started listening, watching, participating. And what I realized very quickly is that I had all the players on the bus, but they weren't in the right seats. That began the work of getting the right people in the right seats to really make change, and that really kind of expedited my process.

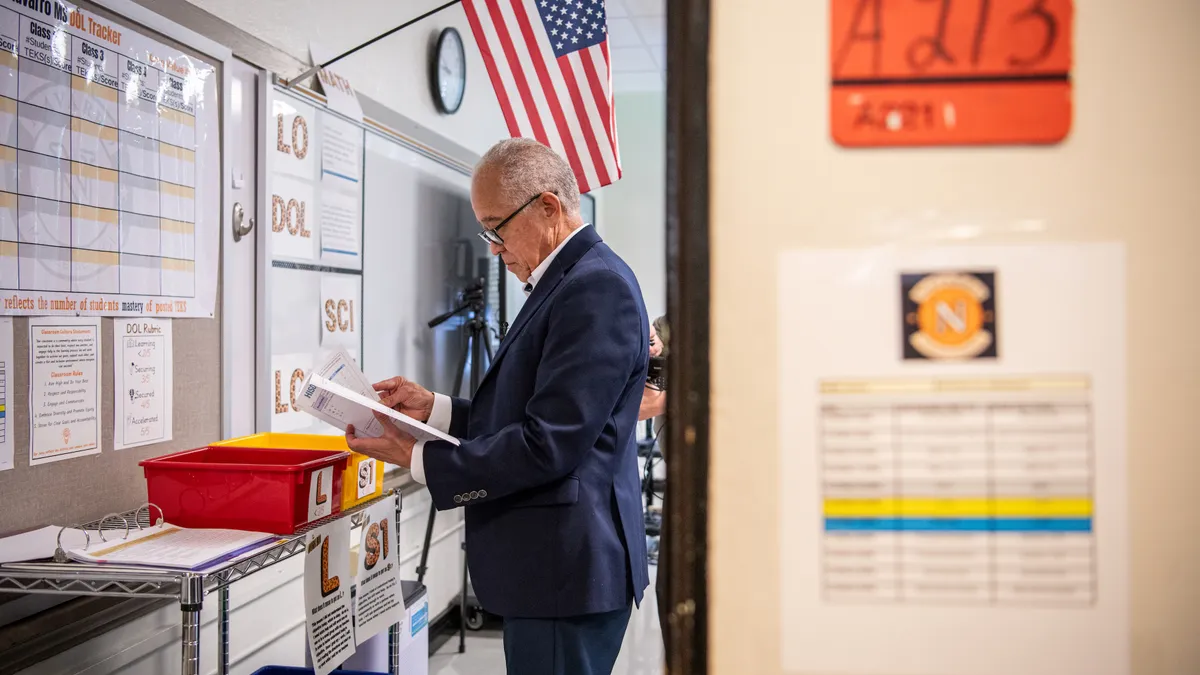

My original goal was to bring back 7th grade by the time I hit my five-year mark, and I did that in year four. In year five, I brought back 8th grade. I'm kind of ahead of the schedule for my original plan, but a lot of it is due to our work from University of Virginia.

UVA runs a program called Partnerships for Leaders in Education. The crux of it is that we use a lot of business practices to make change in education. Having the right people in the seats on the bus and using what we learned through there has really been the backbone of change.

A lot of it is talent management and accountability. We really had to hold people accountable to, No. 1, belief that all kids can learn, and No. 2, belief our kids could do it. A lot of that is a mind shift and a paradigm shift that people have to make.

Our kids come to school with a lot of trauma. We really have to work with getting through their trauma before we can even educate them. So we work really hard on building relationships, using restorative practices, focusing on positive behavioral interventions and supports — all of those things — so our kids feel successful and loved when they come here.

What I realized very quickly is that I had all the players on the bus, but they weren't in the right seats. That began the work of getting the right people in the right seats to really make change, and that really kind of expedited my process.

Sue Mariani

Superintendent, Duquesne City School District

We have a lot of different resources and community partners who support our work and help us make sure our kids get what they need, from local churches to Communities In Schools to the Boys and Girls Club to Auberle — just to name a few who really believe in our kids and helping them have a true successful path to either college or gainful employment.

It's about equity. That’s a big thing I stand on — making sure my kids have what every other kid has.

You’ve also made student voice a priority. What results have you seen so far from those efforts?

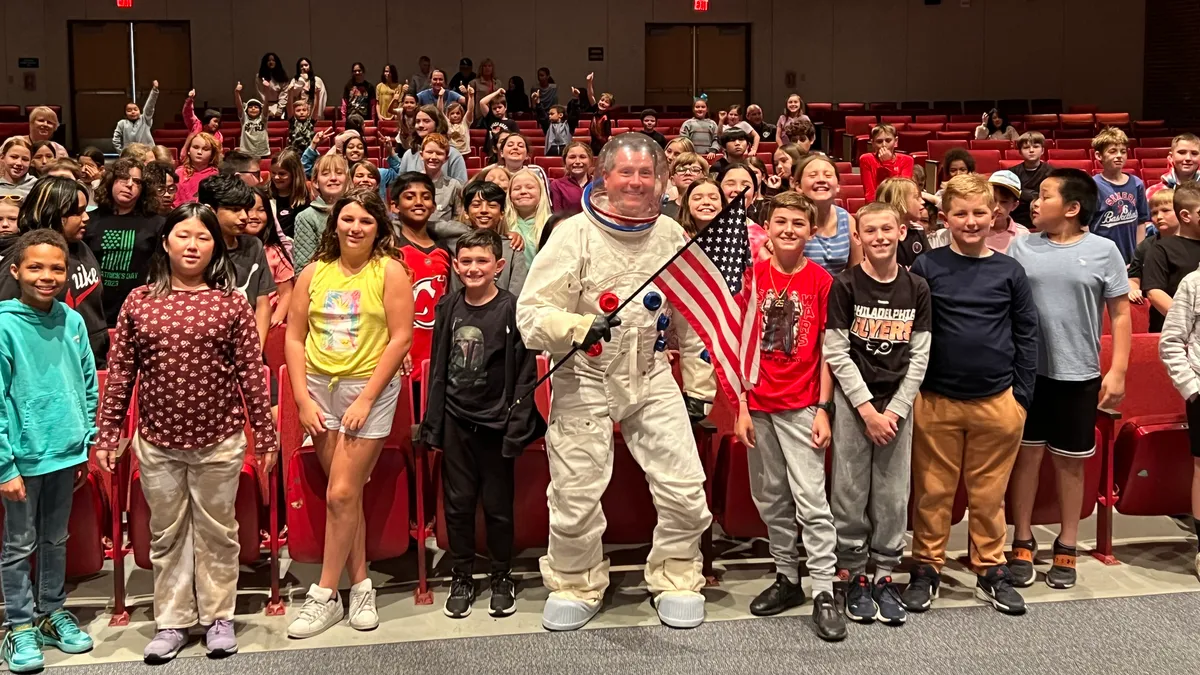

MARIANI: When we talked about electives for middle school, we asked the kids what they wanted. That's how we got our esports lab. That’s what they wanted. And bringing back band. Those are things where we've worked really hard on making sure we heard them, and we gave them choice in what they wanted to see.

Last year, we added horticulture, because that's what the kids wanted. Seeing our kids thrive in an academic setting and giving them an opportunity besides athletics — which has a very historic past here, and we're trying to add to that, of course. But I also want to make sure our kids have other opportunities if you're not an athlete, to make sure you feel success in and out of the classroom.

As part of esports, we also have game design as an elective, and we can only have 16 kids in there because only 16 seats are available. So they do game design, and then they get to play in our esports arena. We have a waitlist for that particular elective, so to me that's a win.

We had 45 kids in band last year in 7th and 8th grade. To me, that's a win that we're getting kids interested in music and showing them how what you're learning in music actually applies to, say, math or reading.

Your next goal is to restore the high school grades. What steps have to be taken to accomplish that?

MARIANI: A lot, to say the least. Right now, my biggest obstacle is locating a building for them. In 2007, the last time they would have had high school kids here, this was a K-12 building. Now as a K-8, there's no room for high school kids.

We're really working hard on identifying where we can put 9th through 12th graders for the future so we can get our kids back.

Our biggest obstacle is identifying and solidifying where we can send them to school in the meantime. We're working hard to create an innovative approach to high school and doing something different, and that's going to take a lot of conversations back and forth with the Pennsylvania Department of Education, convincing them that we're still meeting the high school graduation requirements while we're doing something that's a little innovative and maybe a little thinking outside the box.

We don't want to get our high school kids back and then, in a couple of years, we're back in the same situation where we financially can't make it work. So we need to make sure whatever plan we put together will be sustainable for the long-term future, not just the immediate future.

Sue Mariani

Superintendent, Duquesne City School District

Our middle school kids have thrived in what we've been able to provide them and in hands-on learning and opportunities to make learning relevant through project-based learning. We want to continue that into high school, as well as expand our resources and make sure students have what they need to be successful in life.

As a district in receivership, what does the conversation with the state Department of Education and other stakeholders look like in terms of the resources and finances needed to restore high school sustainably?

MARIANI: Right now, we pay approximately $5 million to East Allegheny and West Mifflin to educate our 9th- through 12th-graders. Bringing $5 million back into the school district will help tremendously.

We've really been putting together a bunch of different scenarios on what this looks like for the future. We've been working really hard on that particular aspect and working directly with the Pennsylvania Department of Education.

We don't want to get our high school kids back and then, in a couple of years, we're back in the same situation where we financially can't make it work. So we need to make sure whatever plan we put together will be sustainable for the long-term future, not just the immediate future.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards