Just beyond the schoolhouse doors of Shiwi Ts'ana Elementary School in Zuni, New Mexico, stand tall buttes with flat tops, steep sides, and rock formations that turn a golden color as the sun dips in the sky.

It's a breathtaking sight that more children and school staff will enjoy once an outdoor learning space is completed at the end of this summer.

"We live in a high type of desert area, but we have a lot of pretty views," said Zuni Public Schools Director of Finance Martin Romine. "We want to get [students] out where they can enjoy nature."

The $1.2 million project will include construction of Wi-Fi accessible stadium seating that will sit next to the school playground so kids can easily move between recess and class time. Construction will start as soon as this school year ends and should finish by the time students return for the fall, Romine said.

Like Shiwi Ts'ana Elementary, schools across the country are anticipating a burst of federally funded facility upgrades this summer. The timing coincides with a loosening of backlogged projects and the summer break that makes school construction logistically easier with fewer students and staffs on campuses.

Although Congress approved the pandemic Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief funds in 2020 and 2021, it takes months or even years to plan and execute construction projects. Supply chain problems and labor shortages created even more challenges for districts that must spend the funds by federally imposed deadlines depending on the three ESSER allocations. The last and largest allocation at $121.9 billion — known as ESSER III — has an obligation deadline of Sept. 30, 2024 and a spending deadline of Jan. 28, 2025.

"We're hopefully making a difference in how kids view school and in their enthusiasm levels about coming to school, because we're doing things that haven't been done before."

Martin Romine

Director of finance for Zuni Public Schools

In Zuni, the district is also gearing up for summer construction of a $1.3 million outdoor learning area with a pond that captures rainwater and elevated teaching platforms for its middle school. Romine said it will be an inviting space for lessons, lunch and after-school activities.

"The money has been very beneficial to allow us to complete projects that we hadn't even thought about before the money became available," said Romine. "We're hopefully making a difference in how kids view school and in their enthusiasm levels about coming to school, because we're doing things that haven't been done before."

Prepandemic construction needs

Across the nation, schools are setting aside some of their COVID-19 recovery funds to improve facilities by replacing doors and windows, upgrading heating and cooling systems, building new roofs, modernizing classroom lighting, enhancing security and more.

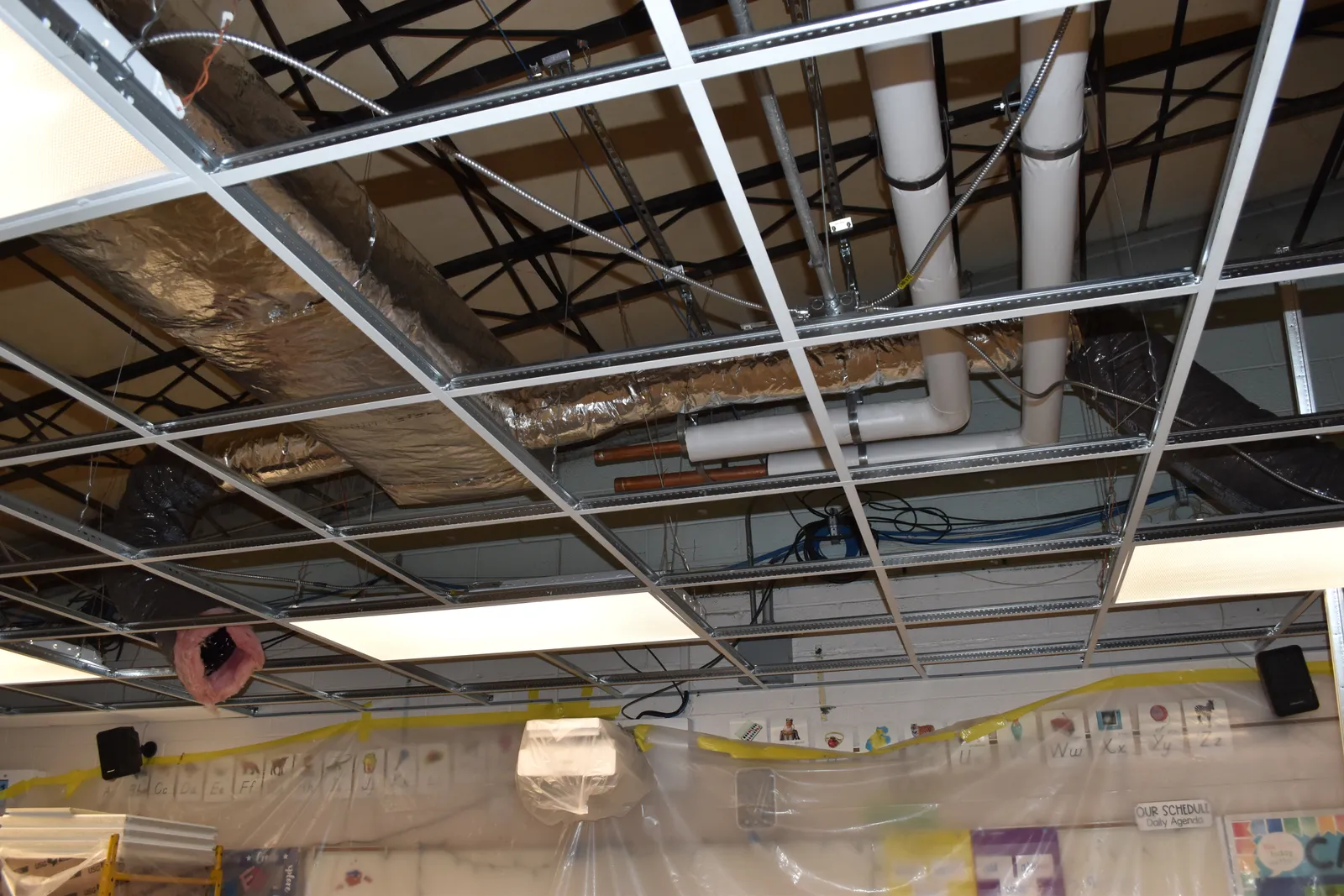

According to data services firm Burbio, 23.9% of about 6,500 school districts' ESSER III spending plans — representing about $92 billion — dedicate money to facilities and operations. Repairing or replacing HVAC systems and ventilation is the No. 1 project, followed by facility improvements to prevent illness, according to Burbio's research as of March.

Districts spend one-fourth of ESSER III funds on facilities

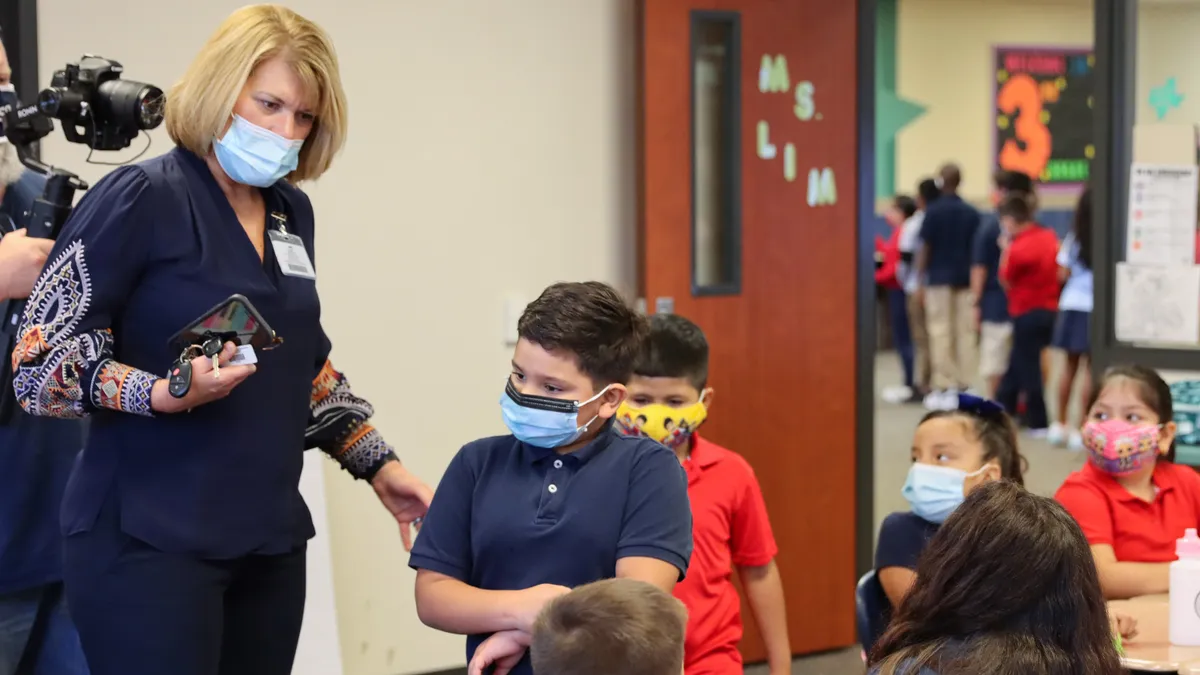

Healthy and functional airflow became a priority for facility projects as schools tried to minimize the spread of COVID and lure students and staff back onto campuses after months of remote learning.

But actually, many school administrators had known years before the pandemic that their HVAC systems needed replacement or repair. According to a U.S. Government Accountability Office report from 2020, an estimated 41% of districts needed to update or replace HVAC systems in at least half of their schools — representing about 36,000 schools nationwide.

Many school and district leaders say there has never before been such a demand for facility improvements that has aligned with an unprecedented influx of flexible federal funding.

"I would say that the extra dollars have been amazing for our school district," said Trisha Schock, executive director of administrative services for North Central ESD 171 in Wenatchee, Washington. The district provides education-related services to 29 public school districts, as well as a tribal school, a charter school and several private schools.

In addition to funding for capital improvements, the ESSER money has supported increased staffing, academic interventions, social-emotional outreach, enhanced curriculum, meals for students and more, Schock said.

"Just so many positive things have been able to be purchased," Schock said.

In Dearborn, Michigan, the school system will continue work this summer to add air conditioning to eight — and possibly nine — schools. Construction has already started, with workers putting in air ducts one classroom at a time as students temporarily move to other spaces in the building. By planning the work in these stages, the district hopes to complete the bulk of the project over the summer months, according to its website.

Only about one-third of the district's schools have air conditioning. The ESSER-supported project is the district’s first large-scale work to add air conditioning to its older buildings. After a November 2019 bond proposal to upgrade the district's schools failed by a few hundred votes, ESSER is allowing the district to move forward on some projects, said David Mustonen, Dearborn Public Schools' director of communications and marketing.

Research in 2022 by the Association of School Business Officials International into ESSER spending practices, highlights administrators' hopes that building improvements will make schools safer and better outfitted for active student learning and engagement.

"Our old buildings were repaired and our HVAC units were replaced along with replacing LED lighting at all schools in order to provide the best learning environment possible," one district administrator from Louisiana told ASBO.

Roadblocks to construction

School communities' enthusiasm and optimism to improve school infrastructure with billions of dollars from the federal government however has, in many places, been deflated by hard realities.

Delays getting equipment and materials due to pandemic-related supply chain woes has meant extending timelines for construction projects. For example, there have been delays of 10 to 15 months for various HVAC, window, door and roof replacement projects, said Elleka Yost, director of advocacy for ASBO.

"Unexpected delays caused by supply chain issues and labor shortages in the construction sector are a huge concern for districts seeking to use funds for such purposes," Yost said.

The Warden School District in Washington began HVAC and chiller replacement projects in February 2022, with an anticipated completion date of August 2022. But as of early April, neither had been finished.

The contractor had multiple delays on products and equipment along with a staffing shortage, according to information Schock received from the district.

At the 1,100-student Zuni school system, Romine is worried about the timing of another ESSER-funded project. A pool building, which has sat boarded up for the past 12 years, is set to get new HVAC and dehumidifying units. While the pool and its diving board are in good shape, the facility is unusable without proper air and ventilation systems, he said.

Many in this rural community are hoping the $1 million project can be completed because once it is, it will be the only swimming pool for area residents and for students.

"Now this one concerns me, because if the drawings take six months, it's going to put us up against a very close deadline to get all the equipment in and get it installed before the funds expire," Romine said.

Another ESSER-funded contract to replace the chiller at Zuni High School was signed in January 2022, but is only 85% complete as contractors wait on needed parts, Romine said.

Another project to replace the HVAC at Twin Buttes Cyber Academy — paid for with $1.7 million from the federal recovery money — wrapped up last fall. The district had planned for that upgrade even before the pandemic, giving it a running start when the ESSER money was allocated, Romine said.

"Unexpected delays caused by supply chain issues and labor shortages in the construction sector are a huge concern for districts seeking to use funds for such purposes."

Elleka Yost

Director of advocacy for the Association of School Business Officials International

Along with project delays, inflation has driven up the costs of materials. Inflation caused Dearborn Public Schools to add $12 million onto its total $52 million budget for air conditioning at certain schools and additional classrooms at an elementary school.

Increased estimates for projects are causing districts to complete work in phases, such as choosing to repair a roof in sections rather than all at once, Yost said.

In some areas, districts incurred delays and rising costs because they were competing with other districts' projects or with non-school projects. As school districts across the country became eligible to hit “go” on construction projects, so too did their neighboring districts.

Smaller and rural districts had the hardest time finding bidders for projects. In fact, there are cases where districts received no bids at all for projects, Yost said.

Although demand for contractors has slowed and districts are having an easier time finding firms to work with, Yost said, labor shortages are more acute now. If there are no qualified people to do the work, it can't be done even if the funding and supplies are available, she said.

And in some locations, there are internal battles of whether construction is the best use of the one-time federal dollars, particularly where there are pressing needs for academic and social-emotional supports and additional teaching staff.

Rather than pitting academics versus facility upgrades, school construction should be viewed as "part of the strategy to improve student learning," Yost said.

More guidance needed on late liquidation

Still, as school administrators keep a close eye on construction budgets and schedules, they're laser focused on one specific date — Sept. 30, 2024, which is the obligation deadline for ESSER III funding, or when districts must commit to projects. The spending deadline — or the point when districts must pay for supplies and contracts — is Jan. 28, 2025.

The obligation deadline for the second round of funding, ESSER II, is Sept. 30, 2023, and the liquidation deadline is Jan. 28, 2024. ESSER I's obligation and spending deadlines, at Sept. 30, 2022, and Jan. 28, 2023, respectively, have already passed.

To help keep districts in New York stay on track to plan and finish construction projects by the federal deadlines, the state Board of Education required districts to submit requests for ESSER-backed projects by even earlier dates than the federal deadlines. The board asked districts to make submissions to the state for ESSER II construction projects by March 1 and for ESSER III by Oct. 1, according to a Jan. 23 memo.

The U.S. Department of Education has offered to give districts additional time — up to 14 months — to spend down their ESSER dollars, known as late liquidation. It's the type of spending flexibility many administrators were pleading for as they began planning how to spend their allocation.

But guidance has been slow and unclear, say local and national education experts. The department issued specific guidance for ESSER I, and that guidance was released Sept. 29, 2022, a day ahead of the obligation deadline. By then, about 96% of ESSER I funds had been spent.

Only seven states and the District of Columbia applied for and received spending extensions for ESSER I. Those requests represent a delay of $6.6 million — or only about 0.05% — from the total $13.2 billion allocated.

Last week, the Education Department released more details on the late liquidation process for ESSER II. Regarding liquidation extensions for ESSER III — also known as the American Rescue Plan — the guidance only says, "The Department strongly encourages States and local educational agencies (LEAs) and other subgrantees to obligate and liquidate ARP Act funds with urgency for activities that support students’ academic recovery and mental health."

Yost said that while ASBO is grateful for school districts' opportunity to now apply for ESSER II late liquidation, it's unknown — from a practical standpoint — how many districts will be able to leverage it with the September 2023 obligation deadline. "This is only four months out," she said.

Yost said there's a high level of interest from ASBO members in applying for spending extensions for the larger ESSER III allocations, but without clear guidance on how to do so or a guarantee their districts' construction projects will be approved before the deadline, many don't want to risk being out of compliance.

Schock agrees, "I think the obligation requirement is going to become a critical piece for [districts] as they look to the future, because if they can't get that wrapped up because of things outside their control, then that's going to be a concern."

Given the long runway for construction projects and the upcoming end of pandemic recovery funds, guidance is needed now if district leaders want to rely on ESSER III spending extensions, Yost said.

"It's been frustrating on our end," said Yost. ASBO is advising members to obligate funds using the original timelines, even if that means some construction projects have to be canceled and money reallocated for other initiatives that have shorter obligation and spending timelines.

"It's not financially prudent, so we need to act as if the flexibility is not available," Yost said.