Like many other high-poverty Midwest cities, Middletown, Ohio, has grappled with shifts in local industry and the employment challenges that come with it — a plight captured in J. D. Vance's novel, "Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis," now a film on Netflix.

The local school district, Middletown City School District, serves 6,400 students and has a 99% free and reduced-price lunch rate. Even without a pandemic and a national reckoning over systemic racism and inequity, it is a scenario where transformational leadership is imperative.

And one where Superintendent Marlon Styles has been "a game-changer," Middletown Board of Education President Chris Urso tells Education Dive. While the district's prior leadership was good, he said, Styles brought a vision for transformation needed to move its schools forward.

"He attracts people to want to work here."

Chris Urso

President, Middletown Board of Education

"The mode of leadership was very direct," Urso said. "It wasn't transformative in the sense of bringing stakeholders together, being innovative, trying to think outside of the box. Marlon has really reset our district in all kinds of different ways."

Where the district used to be a stopover for educators looking to gain professional development, it's now a destination, he said. "He attracts people to want to work here."

Advocating for equity in Middletown and beyond

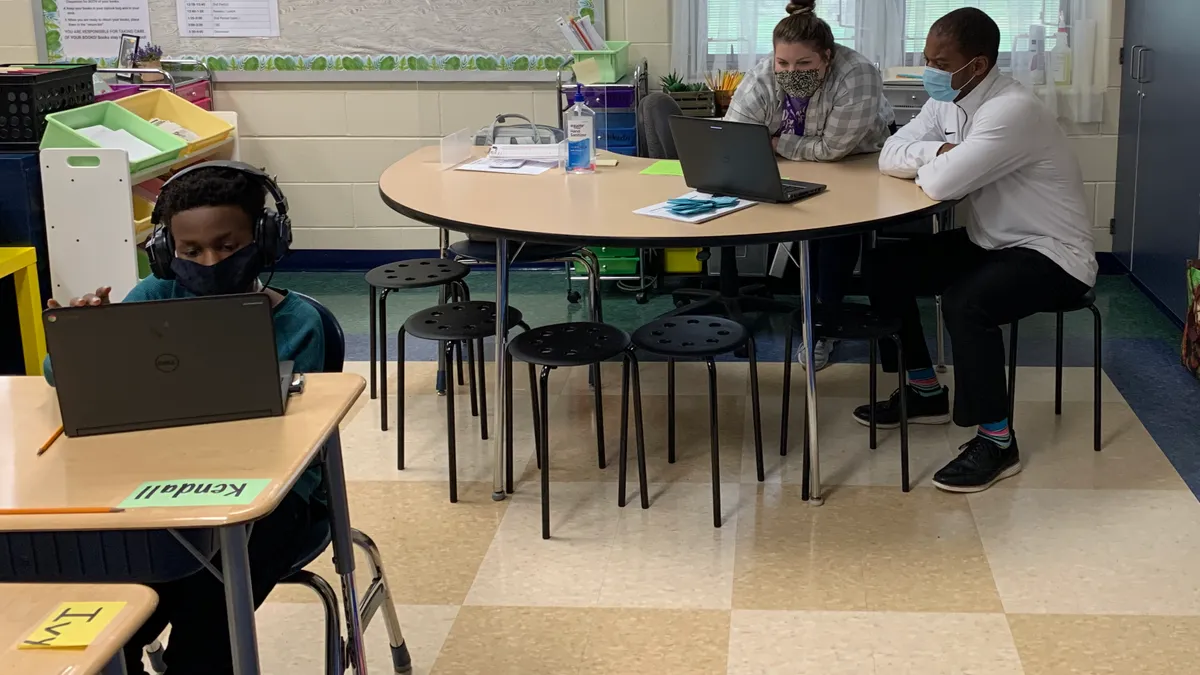

An agenda focused on technological transformation also set the district up to face the COVID-19 pandemic. And while hurdles have persisted around internet access, Styles has become a vocal supporter of closing the homework gap on the national stage.

In March, he estimated to The Wall Street Journal that 20% of the district's students still lacked home internet or device access. And during a May virtual briefing to the House Committee on Education and Labor, he detailed the struggles of families in his district, called for lawmakers to move on closing gaps in access and equity further exacerbated by the pandemic, and stated he continues to lose sleep over the students who need access.

"The equity gap that exists in this country between the haves and have-nots is on center stage right now," Styles told Education Dive in April. "We’ve got kids across this country and here in Middletown who go home and don’t have access to Wi-Fi and maybe not even a device in their home. But right now across the country, we’re celebrating e-learning, virtual learning, whatever kind of learning you want to call it."

"It’s not an equitable model," he said. "I think it’s time we stand up and do something about it as a country."

But more so than access, his first concern when the pandemic hit — like many others in his position — was ensuring the basic needs of students and their families were being met.

"For us, the first thing on that list was not to make sure e-learning was being taken care of," Styles said earlier. "It was making sure our kids’ basic human needs are being met. Food was a big deal of that."

In April, the city's food service and transportation departments were working with volunteers to distribute an average of 4,500 meal bags containing a breakfast and lunch from 30 locations citywide throughout the week, scaled to two volunteers per location for health and safety reasons. The potential for a call to halt distribution due to safety concerns was another area he lost sleep over.

Of course, these challenges have also been compounded by a summer in which the police-involved deaths of Black Americans led to a national reckoning on systemic racism and inequity. As with his response to the pandemic, Styles has confronted the challenge with frankness and candor, establishing an open dialogue with stakeholders.

"We need to do a better job in the education profession of challenging each other to hold true to what we value in our cores."

Marlon Styles

Superintendent, Middletown City School District

"As a Black male superintendent who has experienced racism, I have really been trying to share my story and activate my voice," Styles told Education Dive in June. Earlier that month, he also penned a letter detailing three recent professional experiences around race and equity that had brought him both joy and pain, committing to action and accountability on advancing equity for all students in the district.

"We need to do a better job in the education profession of challenging each other to hold true to what we value in our cores," Styles said, stressing the importance of modeling the right thing to do.

Ultimately, for Urso, as both a board member and parent, the end result of this work is visible where it matters most.

"Our scores are improving, if that's one marker people want to look at," he said. "But I look at our kids, and I think they're more prideful being in Middletown, and our teachers are jacked up about the work they're doing."

Read more

Read more