Dive Brief:

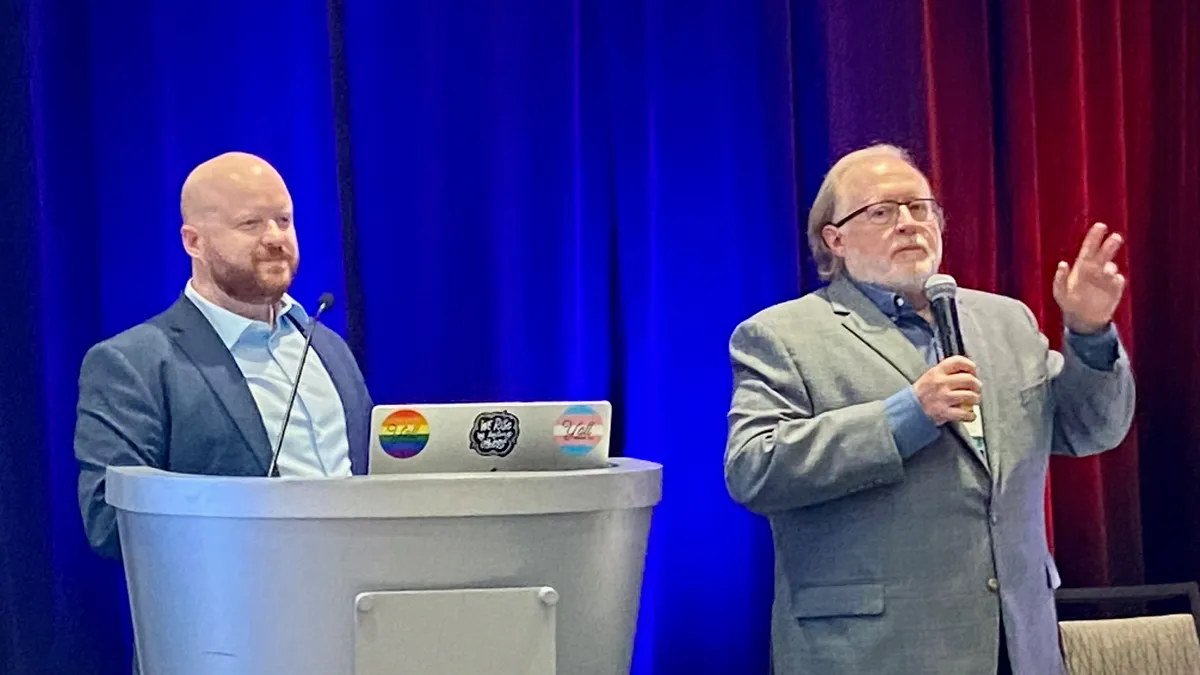

- State education agencies in Ohio and Texas are helping teachers improve their early literacy instruction through multi-tiered systems of support that offer more intensive interventions to young students with the greatest needs, said speakers during a Tuesday session at the U.S. Office of Special Education Programs' Leadership and Project Directors' Conference in Arlington, Va.

- Both states are using OSEP-funded model demonstration project grants to help teachers with early and accurate identification of children with or at risk of dyslexia.

- The presenters said that through training and resource-building for teachers, schools and district personnel, they can improve reading outcomes and begin to close achievement gaps between poor and proficient readers.

Dive Insight:

In Texas, the project organizers are working directly with teachers at four schools, and the work is being led by the University of Houston, said Kristi Santi, a professor in the Department of Education Leadership and Policy Studies.

When first working with a school, the organizers conduct a needs assessment and help teachers and administrators self-identify where their strengths and needs are, as well as the comfort level of teachers for implementing change.

"We want the schools to be the drivers of this process," said Santi.

A school's budget and timeline will be analyzed to determine what resources already exist and what's missing. Data on student reading performance will also be scrutinized, Santi said. Project organizers also help teachers better understand the three tiers of student supports — universal practices for all students, targeted interventions, and intensive instruction.

This work is individualized for each school. "We can't come in with a plan and say, 'This is going to work,' because we want you to tell us what is going to work and what's not going to work based on your district's needs," Santi said.

Teachers are trained in the science of reading and how to integrate the instruction of different elements of early literacy skills. All teachers in the school are trained so those early reading skills are emphasized in all instructional areas, Santi said.

In Ohio, the state has partnered with several universities including Mount St. Joseph University, to support their demonstration project, said Melissa Weber-Mayrer, director of the Office of Approaches to Teaching and Professional Learning at the Ohio Department of Education.

At the state level, the department has developed several documents including Ohio's Dyslexia Handbook to share best practices for universal screening, intervention and remediation for children at risk of having dyslexia.

Additionally, the state has a learning management course for K-12 teachers. About 22,000 kindergarten and 1st grade teachers took the course in the first year.

Wendy Strickler, an assistant professor in reading science and director of teacher advancement programs at Mount St. Joseph University, said that like Texas, the Ohio model demonstration project — which is working directly with three schools — is aimed at helping the schools make more accurate decisions about which students are truly at risk for dyslexia.

And like Texas, Ohio facilitators help schools analyze programs that are working well and areas that need improvement, Strickler said.

Teachers have received training on reading instruction, and much effort has been made to avoid "drilling and killing" exercises and to use "happy" and engaging lessons, she said. Part of this work also includes parent engagement efforts so early reading practice can extend from school to the home.

The grant also allowed two educators from each school to earn their certificate in dyslexia instruction, Strickler said.