SAN DIEGO — Examining data on when cameras capture the movements of bobcats, birds and other wildlife species in San Diego County’s river parks, the student teachers consider questions they would ask staff members and volunteers who oversee the conservation of the watershed.

Is there a correlation between bobcat sightings and other animals? What time of night do most sightings occur?

It’s the same lesson they’ll lead with 5th-graders at elementary schools in the High Tech High network — a group of 16 charter schools clustered in two areas of the county that emphasize equity and project-based instruction.

It’s also the type of authentic and deeper engagement with a topic that then-doctoral student Sarah Fine and Harvard education professor Jal Mehta were looking for 10 years ago when they set out to discover successful high schools in which learning was about more than test scores.

Next month, Fine and Mehta would have been traveling to Louisville, Kentucky, to accept the 2020 Grawemeyer Award in Education, presented by the University of Louisville, for their book, “In Search of Deeper Learning: The Quest to Remake the American High School,” published last year. The award ceremony has now been postponed due to COVID-19.

Their study of 30 high schools revealed very different approaches to student success — from a no-excuses, teacher-directed model to a John Dewey-inspired approach in which students take a more active role in their learning.

High Tech High fit that latter profile, but Fine says her first impressions were quite mixed.

“It was confusing. It looked terribly chaotic,” she says. “But I could tell the kids were engaged. I could tell the kids were joyful.”

Fine felt drawn enough to the model that she came back to teach, first taking a job as a substitute. She now directs the Teaching Apprenticeship Program at High Tech High’s Graduate School of Education, which prepares future teachers to implement High Tech High’s approach to deeper learning.

The apprenticeship is a two-year program with “immersive student teaching” as candidates earn their credential and their graduate degree, Fine says. Similar to other teacher residency programs, the model is an example of how some in the teacher preparation field are trying to eliminate the gaps between what future teachers learn in their programs and the realities of leading a classroom.

“Our graduate school is incredibly tightly aligned with what our schools are trying to do,” Fine says.

Learning the practice of teaching

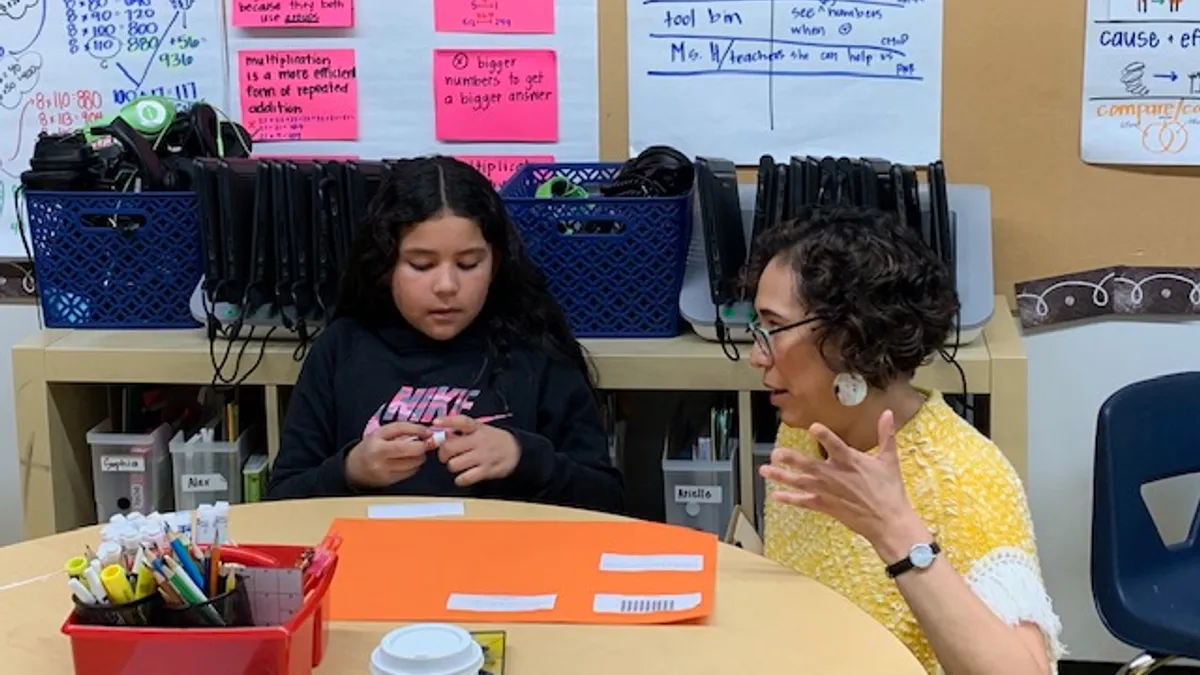

As with the river park wildlife project, candidates practice the lessons they’ll lead with students, receiving feedback and suggestions from Fine and their peers. In classrooms four days a week, first-year apprentices work alongside a High Tech teacher and take the lead with some lessons.

During a recent morning meeting at High Tech Elementary Explorer, 4th grade teacher Meg Hassey asks first-year apprentice Melina Aquirre how students responded when she covered the class for a day.

“It went well. They didn’t question anything. They just knew the flow,” says Aquirre, who has children at the school and worked as an academic coach, like an instructional assistant, before entering the graduate program.

The two discuss how Aquirre should handle an activity on division later that morning and they brainstorm which three lessons Aquirre should include in a portfolio she’ll need to submit to earn her credential. “The purpose of the cycle is that you’re using data to inform the next lesson,” Hassey tells her.

Addy Rigdon, a second-year apprentice, is already leading a kindergarten classroom at Explorer. From North Carolina, she moved to San Diego even before the apprenticeship program was approved by the state because she was specifically looking for a school that was both project-based and had an anti-bias focus.

“They do stand by that,” she says as she helps a boy in an orange trucker hat choose from a chart what job he wants for the day — author or illustrator. In her preparation, she says, candidates learn to do “mental checks of who you’ve been calling on.”

As she gathers students on the rug, Rigdon explains their math task for the morning — tackling a problem in which the answer will be one more than 10. Instead of having the students count together, she sends them to their tables to work on a math story using a process called cognitively guided instruction. It’s a technique used across all schools in the network that that emphasizes “thinking and reasoning over memorizing,” Fine says.

One boy draws rows of squares, using his knowledge of how to represent 10. For those who can’t recall that strategy, Rigdon will help them to “push that efficiency along.”

In Hassey’s classroom, students are also scattered on the floor, at high tables and working in pairs to compare and contrast strategies for dividing 45 by cutting and pasting different strips of paper on a poster. It’s the lesson Aquirre was preparing for that morning. As the 4th-graders work, she checks in with them, looking for those willing to explain to the class how they decided strategies were the same or different.

“This is just a picture version of this,” explains one boy, pointing first to an illustration of nine rows of five and then to a sentence describing a multiplication math fact.

‘A level of rigor’

With hallways full of student work, and students and teachers meeting one-on-one outside classrooms, High Tech schools look more like “design firms” than schools, Fine says. “Our schools are deliberately trying not to feel like school. There is ownership over the space.”

Mehta describes High Tech High schools as fostering a balance between a supportive school climate and having high academic expectations. Too often, he says, there is a “broader educational dialogue in which things ping pong from one extreme to the other.”

“The ethos of the place was very positive and warm,” he says, remembering a scene in which students rushed to help a peer who had dropped his lunch tray instead of laughing at him. “But there was a level of rigor in the expectations of the projects.”

A recent report from the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine delves into changing expectations for the teacher workforce, including the emphasis on deeper learning. It describes deeper learning as an educational experience in which students are building on their existing knowledge, connecting concepts across disciplines, identifying patterns, evaluating new ideas and are able to critically “examine the logic of an argument.”

Examples posted on school websites provide a glimpse into the big-picture topics High Tech High students explore over several weeks: a 2nd grade project titled “What can the average San Diego citizen do to protect our local environment and its inhabitants?” and a middle school challenge in which students used digital tools to design an accessible play area for a new school in the network.

As “deeper learning” becomes one of the latest buzzwords in education, Mehta says there’s also a danger in educators viewing it as another fad or those pitching professional development sessions trying to boil it down to five easy steps. In fact, one interview with him following the release of the book suggested Mehta and Fine had developed the “recipe” for teaching students to be analytical, critical and creative thinkers.

“There is no recipe for deeper learning,” Mehta says.

Addressing inequities

Fine says some of the High Tech High network’s most successful teachers are those who have a traditional background and are now shifting to High Tech’s project-based approach. “It’s a delight for them,” she says.

But as the network has grown, leaders, she adds, have also recognized the need for more systems and structures within the larger project-based approach, especially because the model can be “exhausting” if teachers think they have to constantly create new projects, she says.

Fine’s time with the apprentices on a Friday afternoon is an example of how the graduate school is equipping beginning teachers to address specific writing skills within the project framework. Looking at 9th-grade essays, the apprentices discuss students’ use of commas and conjunctions to form more complex sentences.

“What are some potential mini lessons you could teach?” she asks them. One apprentice suggests a review of how to use commas with introductory elements in a sentence. Another suggests how to properly use “but” because he saw some students write sentences in which the first and second clauses didn’t contradict each other.

Apprentices, Fine says, talk a lot about implementing “instructional routines that can lie inside of projects” in which “kids carry the cognitive load.”

The authors of the National Academies report also note teacher preparation programs need to prepare educators to recognize the influence of students’ culture in their learning.

“As teachers embark on instruction based on changing standards, they must also consider how they will foster instruction that is responsive to the multicultural and multilingual diversity represented in their classrooms and look for opportunities to center cultural knowledge, practices and world views in ways that address inequities in the classroom,” they wrote.

Students in the apprenticeship participate in a year-long seminar on equity and culturally responsive teaching in line with the network’s emphasis on those issues.

Mehta notes there’s nothing innovative about developing schools in which students are engaged and connected to the material they are studying and have some choice in what they want to learn.

“We say that the aspirations are not new,” he says. “What would be new is if we delivered on that for all students.”