When thinking of classes on artificial intelligence, you probably imagine students on a computer writing code. But that’s not where Joseph South, chief learning officer for the International Society for Technology in Education, says educators should start.

Instead, teachers should help students learn how to approach decisions the way digital programming might — by working through information, finding patterns and making a choice.

“At ISTE, we feel strongly students need to learn how the digital world works,” South said. “Those skills would be incomplete without an understanding of how these extremely powerful tools are working."

Computers and digital devices are as ubiquitous to today’s students as pencils and pens were to their grandparents. People commonly call on Siri to send a text message or allow Netflix to select the next show to watch. Underpinning those actions is artificial intelligence, or AI, which uses a system of data analysis and algorithms to help machines make decisions like which letter to pick for a word that sounds like “hey” and not “hay,” or how to select a movie a “Star Wars" fan might want to see next based on available information.

Experts believe having students learn about machine learning is a crucial piece of learning how AI technology works and should start when they're young. Then as students get older, the curriculum can broaden to include ethical issues, such as AI bias or how data is collected and applied, and who ultimately owns it.

Crucially, though, teachers must understand the topic themselves to be able to help steer students toward fluency of their own.

Using machine learning for problem solving

When teaching students the basics of machine learning and how AI operates, Michael Daley, an associate professor and director of the Center for Professional Development & Education Reform at the Warner School of Education at the University of Rochester, suggests classes should learn how to apply a machine learning approach to solve problems.

In other words, they should learn how to think like a computer.

“We know there is an explosion of big data,” Daley said. “It’s an awareness we believe people should be learning in school, because their data is shared everywhere. We want them to have an understanding of big data and how big data is processed.”

This interest has spurred Daley to launch EAGER, a two-year project funded by the National Science Foundation to help build machine-learning mindsets in K-12 students.

One part of the project is a program that turns data into a visual representation, such as a pictograph of a face. For example, the program may reflect the abundance of beetles in a specific region by having certain facial features appear more or less prominently in a visual representation. Eyebrows may represent the air temperature in a given area, while the nose on the figure may demonstrate humidity, and the ears might stand for the number of beetles. These characteristics change based on the data: Eyebrows can be thicker and ears smaller, for instance.

Students can then visualize the data without getting lost in the numbers. They can also drag the pictographs on top of each other to look at clusters, such as comparing the faces with thinner eyebrows representing lower air temperature regions. Patterns then appear, pointing to evidence that can help students create a hypothesis.

“We do think this way of asking questions is an emerging way to do science,” Daley said.

Standards — and laws — are needed

South said ISTE began thinking about the rise of AI about five years ago, with a focus on how to help teachers instruct students on the technology and related ethical issues around designing for machines.

“We wanted students to participate in activities so they could understand how AI functions and the ethical issues that arise,” he said. “AI reflects human values and biases, and we wanted to expand the numbers and types of students designing AI.”

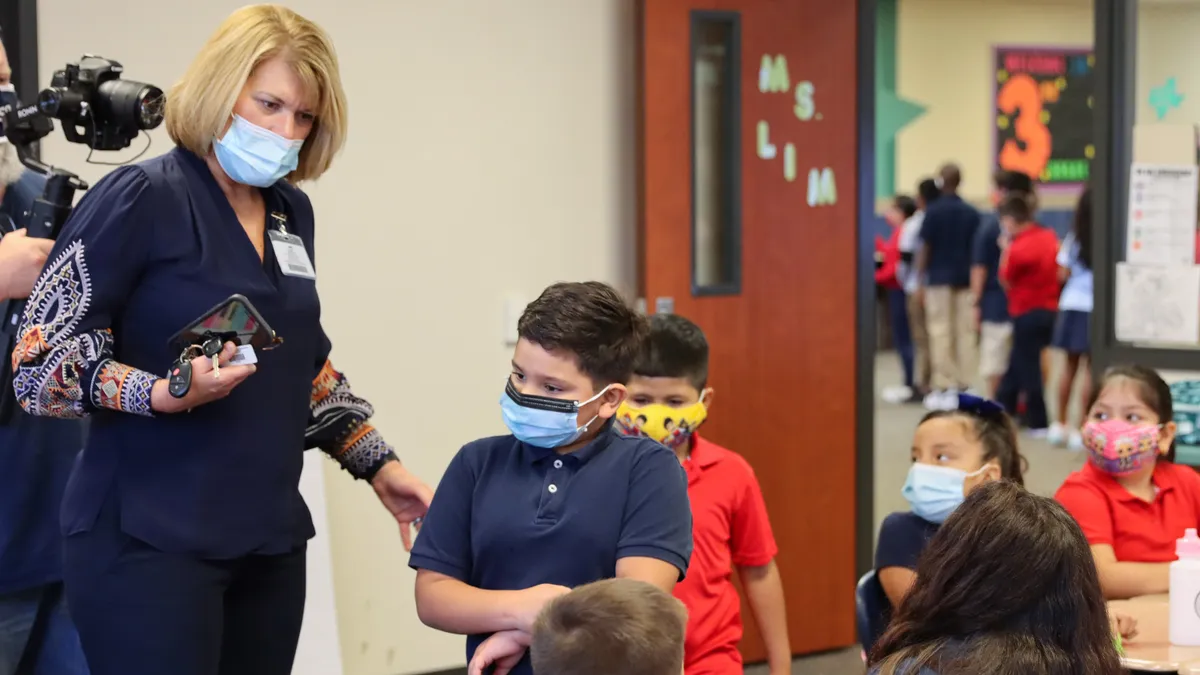

To that end, ISTE developed a partnership with GM in 2017 that began by teaching educators how to teach the subject. To date, more than 1,500 teachers have been trained in how to think about machine learning — and they in turn have taught over 3 million students, South said.

The program is free and launched with high schools in California, Texas, and Michigan that serve high-poverty populations or had populations historically underrepresented in STEM fields.

That approach stemmed from seeing AI as an “equity issue,” said Nancye Blair Black, ISTE-GM AI Explorations Project Lead. The program has since expanded into teaching guides that focus on elementary school curriculum, secondary schools, computer science, ethics and AI.

“Children and humans, in general, deserve to know how their world works and have a say in how their world works,” Black said. “They should know the pros and cons of AI, what works well, the societal impacts, and how AI can solve problems.”

One challenge — and motivation — for creating an AI curriculum has been a lack of standards, experts said. While most states have computer science standards, building computational models and understanding machine learning is an entirely different field.

But it should start with young students and not wait until upper grades, said Yigal Rosen, a former technology and assessment researcher with the Harvard University Graduate School of Education who now develops AI learning tools for BrainPOP.

"Computational thinking, which is a mindset, needs to start early,” Rosen said. “You have to build those skills starting in elementary school, as opposed to waiting for high school.”

New standards and assessments are also slowly appearing on the global stage. One assessment, the PISA 2025 Learning in the Digital World, will look at how prepared students are at applying computational logic to solve problems, with results expected by December 2027.

Nations are also taking a hard look at how AI is applied and used in everyday life. In the EU, the proposed EU AI Act will apply a scale to the risk of uses for artificial intelligence in certain industries, including AI that scans job applications or the way AI can assign a social score which is then used by a government. The White House also recently released a proposed draft for an AI Bill of Rights to examine the regulation of AI in healthcare, financial services and other sectors.

To Patricia Scanlon, Ireland’s first AI Ambassador and founder and executive chair of SoapBox, a speech recognition tool designed for children’s voices, this concern about how AI is involved in our lives underpins the need to ensure students learn at least a conceptual understanding of machine learning. Whether they end up designing artificial intelligence or are just engaged citizens of the world, knowing how AI works is key.

“Not everybody needs to know every detail,” Scanlon said. “The people who will contribute to AI, not everybody will have to be technical. But you need to know how to evaluate [AI], and how it’s regulated. There are so many aspects in how it’s a part of our lives, and kids are living in that world.”

Dive Awards

Dive Awards