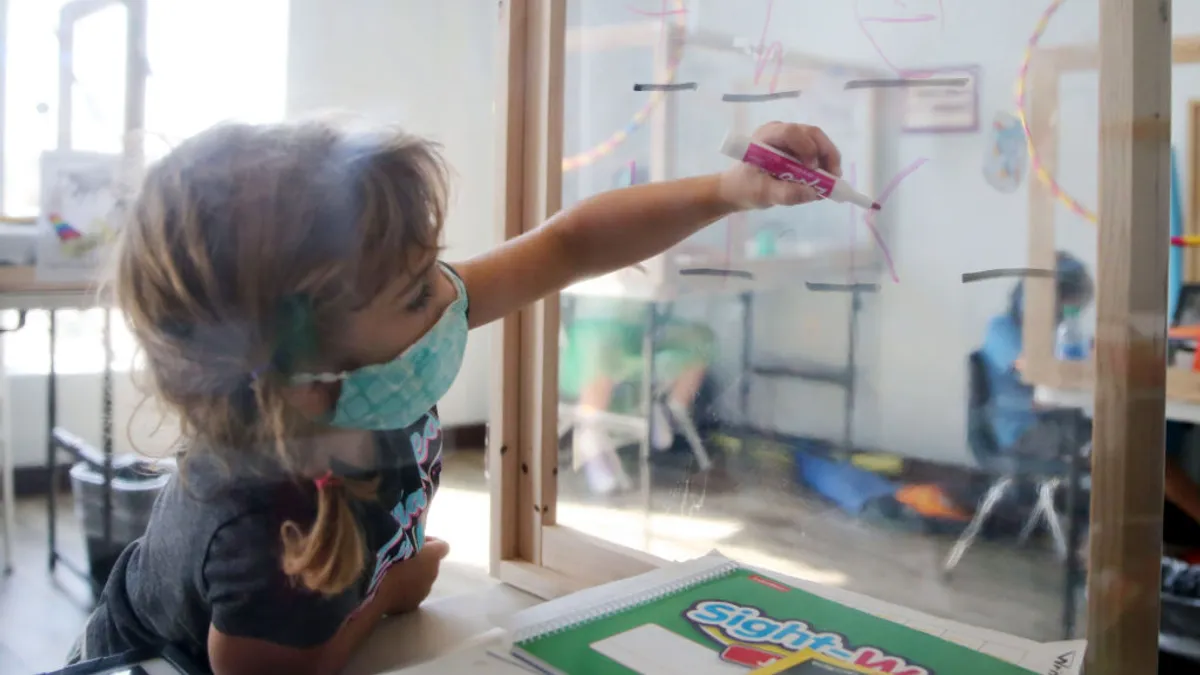

Threat assessments, a formalized approach to preventing potential incidences of K-12 school violence by students, have a growing number of opponents who say students with disabilities, students of color and students from low-income families are disproportionately the focus of investigations. Various civil rights organizations say threat assessments do more harm by contributing to the school-to-prison pipeline than they do to prevent tragedies.

Supporters, however, say threat assessments give school staff a structured system for the sensitive and serious process of gathering information to evaluate the probability of a student causing harm to others. Without it, there is greater potential for school staff to overreact and make rash decisions that would inappropriately — and perhaps disproportionately — push more students toward suspensions, expulsions or arrests.

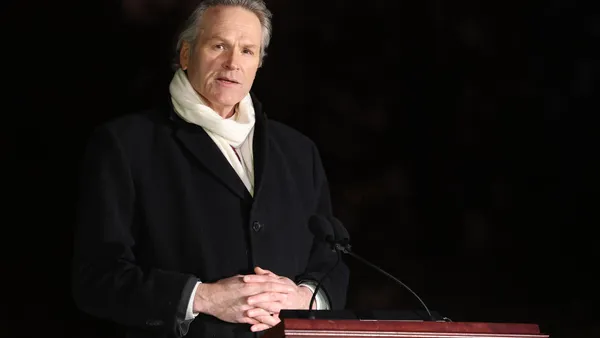

“It's a question of whether they do them intuitively, impulsively, out of fear and anxiety, or they do them systematically with a standard process,” said Dewey Cornell, a clinical psychologist and professor of education at the University of Virginia who has conducted training and research on school threat assessments.

“There's no way that schools can avoid doing threat assessments,” Cornell said. “It's a question of how they're going to do them.”

'Referrals to nowhere'

Opposition to school threat assessments has been building for several years, particularly among civil rights and disability rights groups saying they are trying to sound the alarm about the practice, likening it to trying to prevent brain tumors by giving a CT-scan to anyone with a headache. The CT-scans would perhaps reveal a few people with brain tumors, but excessive x-rays from the scans would lead to elevated cancer risks for more people, they say.

“The population that's getting threat assessed is exponentially larger than any potential shooters. It’s creating a huge harm for many kids,” said Miriam Rollin, a director with the National Center for Youth Law, one of the organizations opposing the practice.

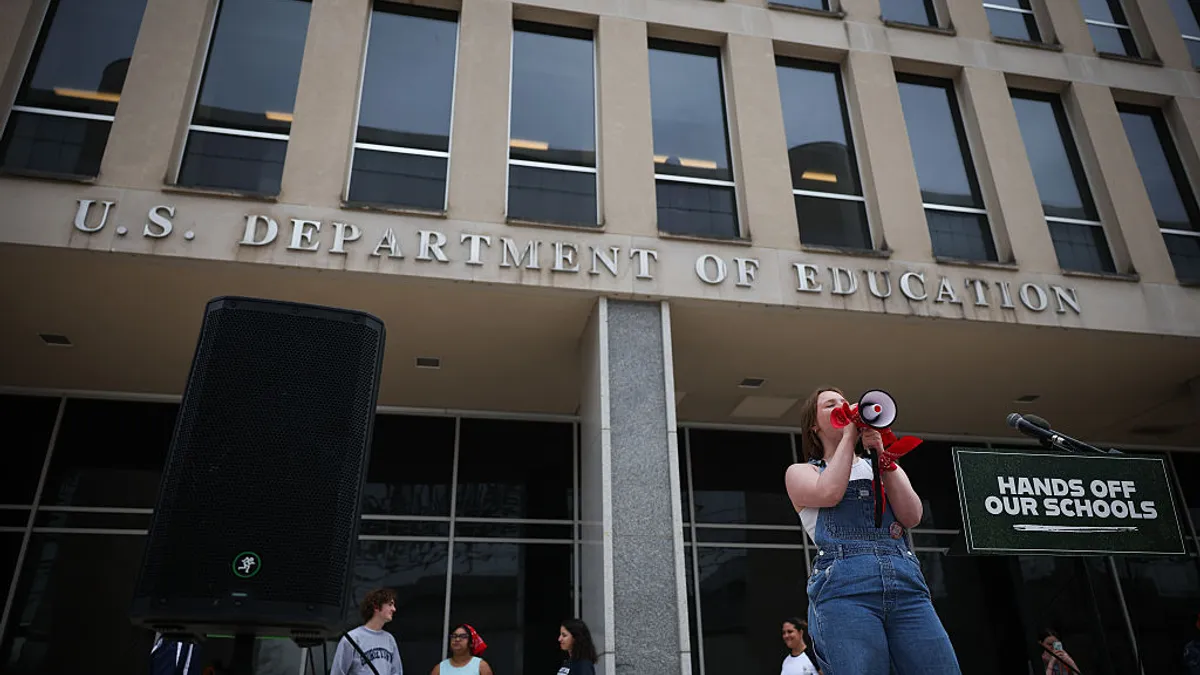

The debate grew louder more recently when the U.S. Department of Education requested public comments on nondiscriminatory practices of school discipline. More than 3,600 were submitted and may be used to assist the department’s Office for Civil Rights in preparing further guidance, technical assistance and other resources. As part of this request, the department specifically asked for opinions on threat assessment practices.

Some organizations and individuals submitting responses asked the Education Department for guidance on the civil rights implications of threat assessments, or that policies be created preventing law enforcement involvement. One group, Dignity in Schools, suggested the term be rephrased to focus more on the supports a student could receive as a result of a threat assessment rather than on labeling students as a threat.

“The population that's getting threat assessed is exponentially larger than any potential shooters. It’s creating a huge harm for many kids.”

Miriam Rollin

a director with the National Center for Youth Law

A group of 50 local, regional, state and national groups, including the National Center for Youth Law, collectively submitted a 7-page letter voicing several concerns about threat assessments. In it, the groups say the approach's intent to connect students who are a focus of a threat assessment with school or community resources rarely happens because of a lack of funding and availability of school-based and community resources and supports.

“Referrals to nowhere; that's not going to help the situation for a kid," Rollin said. "It's an injustice giving a kid a referral for services when there are no services available to them because we're spending all the resources on stuff like cops at schools and threat assessments.”

She added that there’s concern about lasting trauma when students are a focus of a threat assessment.

Informal removals for students with disabilities

Another concern is the potential of threat assessments to bypass legal protections under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act for students with disabilities.

Diane Smith Howard, managing attorney for criminal and juvenile justice for the National Disability Rights Network, said informal school removals are the No. 1 problem state protection and advocacy systems report in regard to school discipline challenges, and that threat and risk assessments are forms of informal removal.

Smith Howard said threat assessment teams often don't include members of a student’s individualized education program in the evaluation of the potential threat. “So the folks who actually know the child and know the child's disability-related needs are not engaged in that process,” Smith Howard said.

When threat assessment teams act outside of the special education process, there is no review of the role of the child’s disability, and IDEA and Section 504 protections are not activated, resulting in potential discrimination on the basis of disability, Smith Howard said.

In the case of risk assessment removals, this results in unofficial removals from schools until a child is deemed not "risky” through the use of a psychological evaluation, which may be at the family’s expense or by an unqualified provider. Many families cannot afford this expense, so the child remains out of school, she said.

A ‘calmer, more common sense’ approach

Cornell disputes these criticisms, saying they are based on a few publicized cases where students were mistreated at school. When used with fidelity, the threat assessment model’s five-step decision tree process provides a problem-solving, conflict resolution approach based on data-driven information that helps school teams determine the true intent of a threat made by a student, as well as what types of interventions to use, he said.

It's a graduated system where the perceived threat, in most cases, can be resolved quickly, because a multidisciplinary team determines the student may have said or done something inappropriate but doesn't have violent tendencies, Cornell said.

“There's no way that schools can avoid doing threat assessments. It's a question of how they're going to do them.”

Dewey Cornell

professor of education at the University of Virginia

Research by Cornell indicates two-thirds of threats studied were classified by school teams as either low-risk or “transient,” which indicates the threat did not pose a serious risk of violence.

“We just think it's a calmer, more common-sense way to deal with student threats,” said Cornell, pointing to research showing rates of suspensions, expulsions and law enforcement action in schools using the Comprehensive School Threat Assessment Guidelines (CSTAG).

It also helps connect students with services that could address their concerning behaviors, he said.

A 2020 report of research over four school years of threat assessments in Virginia, co-written by Cornell, shows 32% of students were referred for school-based counseling, 19% for mental health assessments, and 19% for mental health services inside or outside of the school system, along with additional reviews and services.

Research in the report also showed:

- Of 12,000 threat assessments in the 2017-18 school year, all were apparently resolved without a serious injury.

- In 97% of cases, there was no known attempt to carry out the threat.

- Schools took disciplinary action against students in 71% of threat assessment cases.

- There was consultation with the school resource officer or other school safety specialist in 47% of cases.

Regarding racial disparities, research conducted by Cornell and published in 2018 examined 1,836 threat assessment cases in 779 schools, finding no statistically significant differences among Black, Hispanic and White students in rates of school suspensions, expulsions, school transfers or legal consequences. However, the proportion of Black students referred for threat assessment was 1.3 times higher than of White students.

Students receiving special education services were approximately 3 times more likely to make threats than students in regular education. The research also showed the greatest number of threats were made by 4th-graders (11%) and 5th-graders (11%).

State policies and districts' experiences

Threat assessment approaches in schools have been endorsed as a best practice by the U.S. Secret Service, U.S. Department of Homeland Security and Department of Education.

The use of threat assessments in K-12 schools has grown in the past decade, particularly after the 2018 school shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. In the 2018 legislative session, Florida and Maryland adopted the threat assessment model as a strategy to prevent school violence. The following year, Kentucky, Tennessee, Texas and Washington enacted similar policies, according to research from the Education Commission of the States.

Virginia's Loudoun County Public Schools, which has 81,000 students, conducted thousands of threat assessments over the past 16 years. In those cases, there hasn't been an incident where a threat of violence was carried out, said John Lody, the district’s director of Diagnostic and Prevention Services. Not only has it likely prevented school violence, but the practice has also provided supports to students that take them off a pathway of potential violence, he said.

“Our approach isn't to suspend the student, unless it's absolutely necessary as a safety measure,” Lody said. “Our approach is to resolve the underlying problem that led to the threat in the first place.”

The suspension rate for the district is less than 1% annually, Lody said. He added the approach is more equitable among different student populations because threat assessment teams — there is one for each school — look objectively at information from various sources and make decisions based on each student’s situation.

“Instead of asking, ‘Well, what's wrong with that kid,’ we now started asking, ‘I wonder what happened’ and that changes the whole paradigm.”

Travis Hamblin

director of Student Services for Jordan School District in Utah

Travis Hamblin, who is director of student services for the 56,000-student Jordan School District in Utah, had just completed initial training in the threat assessment model in March 2020. The next day, the pandemic became a reality, and Hamblin turned his focus on helping the school system respond to the public health crisis. Months later, he revisited the training and encouraged other administrators to take it. District leaders and staff have also undergone training in positive behavioral interventions and supports, and in cultural sensitivity and inclusivity practices, he said.

Although the district has just begun to use threat assessment, it’s already led to administrators’ ability to identify students in crisis earlier, Hamblin said.

“What this allows us to do using CSTAG is to use a decision process, to have the actual documentation of our decision process so that we can remove emotion from the equation and look at it logically with relationship-focused, centered, wellness-focused data-informed decision making,” Hamblin said.

“Instead of asking, ‘Well, what's wrong with that kid,’ we now started asking, ‘I wonder what happened?’ And that changes the whole paradigm.”

Making improvements, taking different approaches

Rather than use the threat assessment model, those concerned with the approach said schools should improve upon their multi-tiered systems of support and PBIS practices. They should also ensure IDEA’s child find procedures are being used to identify students who may qualify for special education services.

Rollin said students also need caring, trusting adults in schools who they can build positive relationships with, as well as a safe environment that doesn't include the presence of police.

“The very things that they're doing with law enforcement in schools and threat assessments in schools are undermining safety because it creates a culture that's prison-like, where nobody seeks help for themselves or others,” she said.

Adding more highly qualified staff such as psychologists, social workers and counselors would also help schools respond to students in crisis, Rollin added.

In his research papers, Cornell has advocated for clarifications to threat assessment policies to distinguish the difference between cases of harm against others and threats of self-harm.

Cornell and those concerned about threat assessments say they would support the inclusion of threat assessment data in OCR’s Civil Rights Data Collection. The groups say they want data to include the numbers and demographics of the students referred and any resulting discipline and law enforcement responses, as well as referrals for services and whether those services were provided.

Lody, from Loudoun, said documentation and analysis of the district’s threat assessments have been a challenge because, until recently, there was limited software for easy data management. Documentation can help the district with quality control, such as making sure threat assessment teams are staying compliant with procedures. It can also help the district analyze trends and disaggregate data by gender, race, grades and other factors.

Another challenge is making sure staff in the growing district have recent training in threat assessment practices.

“I've never encountered skepticism on its approach because it works," Lody said. "It really is aimed at preventing acts of violence and getting the help that individuals need who are struggling with a problem, and it's not hard to see how easily this works when put into practice.”