A month ago, during what now feels like the olden days of education, Lorenza Scott, a family liaison coordinator for two community schools in Washington’s Renton School District, had a caseload of 68 low-income students and their families.

But ever since COVID-19 shuttered schools, her caseload has grown to 100, stretched by families who had been barely scraping by before.

“When COVID-19 happened, we saw a huge increase in need,” Scott said. “A lot families who had a stable income, stable housing, things like that, had that no longer.”

The Renton district is affiliated with Communities in Schools, a Virginia-based nonprofit network of 2,300 community schools in 25 states and the District of Columbia that reach about 1.5 million students. Another 5,000 community schools across the country participate in the nonprofit Coalition for Community Schools network, a project of the Institute for Educational Leadership.

Designed for disasters

The impact of the pandemic on schools hit fast and hard. Within the first week schools closed in South Carolina’s Richland and Lexington Counties, Tanika Epps, CEO of Communities in Schools of the Midlands, was helping a family already living in a hotel after being evicted from their home when the mother was laid off. The family was now facing eviction from the hotel because the father also lost his job due to the coronavirus pandemic.

At REACH! Partnership High School in Baltimore’s Clifton Park neighborhood, one of Rhonda McKinney’s first check-in calls was with the mother of a 9th-grader, who burst into tears when McKinney asked how things were going. Just minutes earlier, the mother learned her grandmother had died of COVID-19. McKinney, the school’s community engagement officer, offered to call back at a better time, but the mom kept her on the line.

“She just wanted to have someone on the phone to talk to,” said McKinney.

In both cases, the community schools had partnerships with local service providers, and Epps and McKinney made immediate referrals to help the families.

“The whole [community schools] system is designed to deal with this type of crisis,” explained José Muñoz, director of CCS.

Because the mission of community schools is to create a neighborhood hub through partnerships that bring everything from tutoring and social services to healthcare and enrichment programs directly into schools, proponents of the model say they have the infrastructure and relationships to respond to a crisis like COVID-19 more nimbly and efficiently than many traditional schools.

As soon as schools closed, CCS began holding virtual town hall meetings for school, community, state and national community school leaders to address the most pressing needs, including food distribution, health and mental health care, barriers to remote learning, evictions, and the best way to stay engaged with the most at-risk students — English learners, homeless students, refugees and students with disabilities. About 170 people have participated in each of the four meetings held since March, said Muñoz.

In Washington’s Renton district, when a single parent of three lost patience because one of her children would not listen and had become out-of-control, Scott pulled together what she calls a wraparound team that includes herself, the assistant principal, a school counselor, a therapist and the mom. Between therapy, parenting sessions and general wellness check-ins, the family receives daily phone support.

“With community partners,” said Scott, “you have a lot of hands to help, a lot of hands to get things going.”

In Baltimore, which has one of the most robust community school programs in the country, Maurice McKoy found with local partnerships and relationships in place, “we’ve been able to accomplish at least 80% of what we’ve done” since the pandemic hit. McKoy leads the BellXcel after-school program at Harlem Park Elementary & Middle School, in a neighborhood shaken by violent crime and poverty, where median family income is below $30,000 a year.

When schools first closed, he said it wasn’t unusual for staff to spend 10-12 hours a day on the phone checking in with every student and family. Needs and concerns range from parents in essential jobs asking for help finding child care because they worry about leaving their children home alone during the day to students whose home lives were unpredictable before COVID-19 and are now concerned the added stress of being cooped up will exacerbate an already volatile situation.

“Some [parents’] way of disciplining children is yelling and screaming and cursing,” said McKoy. In a few cases, he’s had to find emergency housing for students who could not remain in their homes.

In these situations, staff rely on their “family tree,” a network of mental health organizations, social workers and other experts who are available to help families in crisis so parents “can have someone to talk to versus taking that stress out on their children,” he said.

The stress takes a toll on teachers and staff as well as families. Every morning, REACH! runs a social-emotional session for staff on Zoom, where they do breathing exercises and check in with each other. They run several other social-emotional programs during the week for students. For fun — and a break from the loneliness and drudgery of staying at home — a school monitor who also happens to be a DJ runs an hour-long virtual dance party every Wednesday.

Using a ‘trauma-informed lens’

In the best of times, community schools serve a vulnerable and marginalized population. A crisis can magnify family stresses and inflame unstable conditions.

“To be very honest, we’re dealing with students who were in crisis before the virus, and it is just going to add a layer of depth to the kind of work that our site coordinators are doing,” said Rey Saldaña, president and CEO of Communities in Schools. He likened school staff to paramedics in these situations and is not the only community school leader to describe their work during the early days of the pandemic as triage.

“Each one of our site coordinators knows the students who are going to be most at risk,” said Saldaña. “They know the students that they need to check with more often because of the safety issues.”

At REACH Academy elementary school in the Oakland Unified School District, staff are on high alert for signs of new or deepening mental health issues and trauma. “We always work through a trauma-informed lens,” said Community School Manager Camila Barbour.

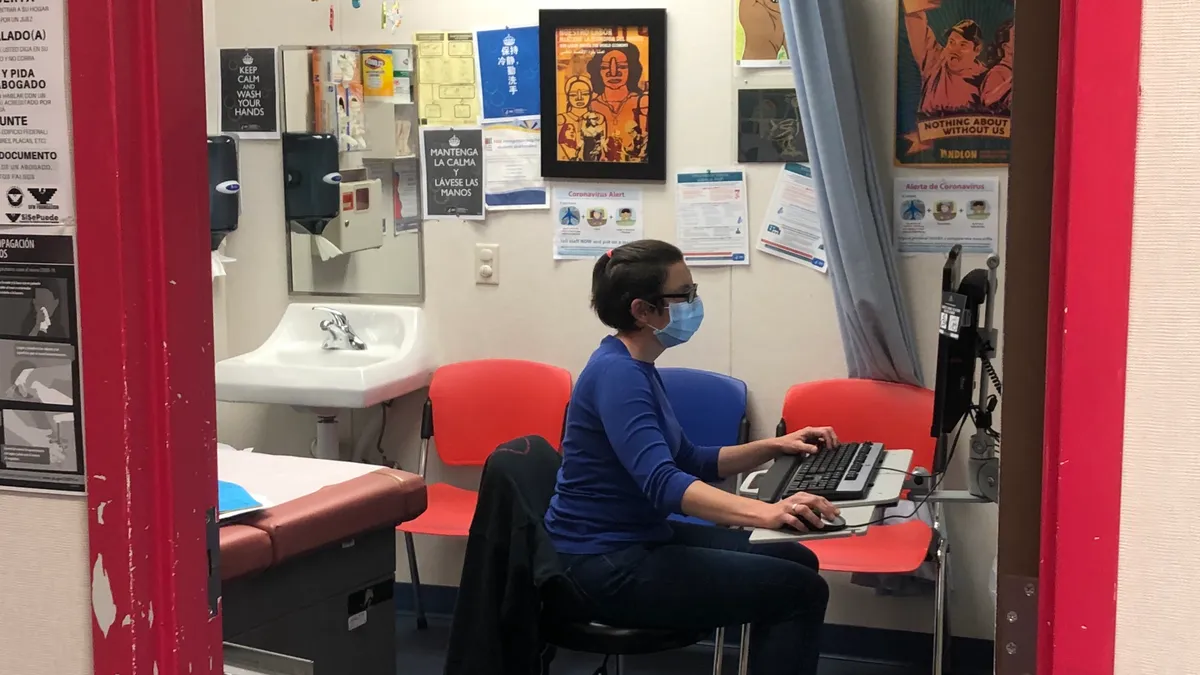

During check-in calls, they use a comprehensive questionnaire to determine how well families are managing stress and refer people for counseling and other services through their network of local partners. Sixteen of the schools have on-site health clinics, and at least three are remaining open during the pandemic; therapy sessions will continue by phone.

OUSD has had time to refine its processes. In 2011, it began transitioning to become the first full-service community school district in the country, serving more than 36,000 students in about 85 schools.

Barbour said the coordinators have developed deep trust between families and school staff over the years. She gives them her cell phone number.

“They have a familiarity with us that we’re going to make sure that everything is going to be alright,” and because of those relationships, Barbour said the stress level for most families is manageable — what she calls “composed anxiety.”

Funding and other challenges

With each natural disaster, community school leaders gain new insights into improving their systems to better help students and families. Their response to COVID-19 is built on lessons from Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and Houston’s Hurricane Harvey 12 years later, which also closed schools for an extended period of time. Leaders are already compiling notes on how things worked this time. Overall, they see more success stories than shortfalls.

“If people were not convinced before, this makes the case for why community schools are important,” said Tauheedah Jackson, deputy director of CCS. Now, she said, advocates need to think about how to sustain and grow the work in the longterm. But with state revenues plummeting because of the crisis, it’s unlikely many states will be able to follow through on some of the budget initiatives they planned for next school year, let alone expand the community school model.

States that once projected an increase in revenues are spending those funds — and more — on COVID-19. For example, Deanna Niebuhr, the California policy and programs director at the nonprofit Opportunity Institute, said Gov. Gavin Newsom's proposal to create a $300 million community schools grant has little chance of making it through the state legislature. Many states are now anticipating cuts in their education budgets.

It’s unclear, however, whether philanthropic foundations will pick up the slack. In late March, Jaime Greene, the executive director of CIS of Renton-Tukwila, said she received a call “from a funder, who had previously invited me to apply for a grant, letting me know they are not accepting any new applications as all resources will be going to support existing grantees in their COVID support efforts. Unfortunately, I imagine receiving more calls like this.”

But around the same time, Epps in South Carolina received the opposite message from two funders who reached out to see what the school needed. One invited her to apply for a new grant of up to $10,000 to help community partners cover the costs of their COVID-19 work.