Just as an SXSW EDU panel of school nutrition experts began in Austin, Texas, Monday afternoon with calls for a nationwide continuation of universal free school meals, media reports began to hint that the expansion would be unlikely.

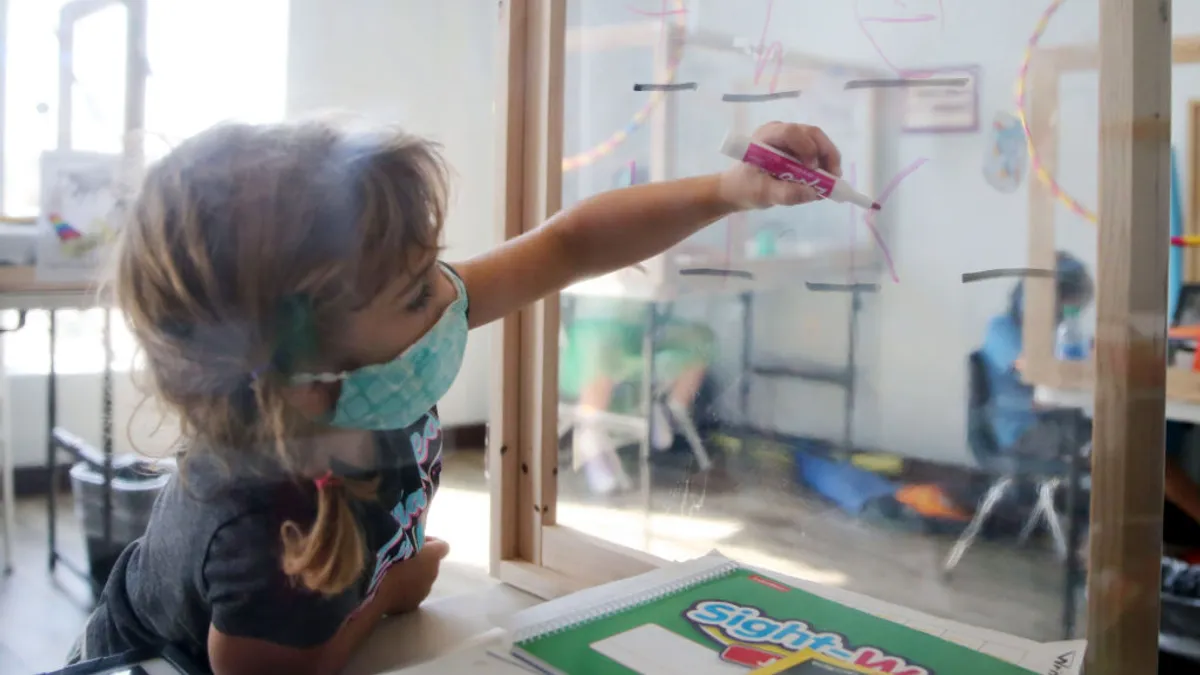

Universal school meals emerged out of pandemic-era waivers designed to help feed hungry children during the crisis. The U.S. Department of Agriculture waivers allowed all K-12 students, rather than only those eligible for free and reduced-price meals, to get free school breakfast and lunch no matter their family’s income from March 2020 through the 2021-22 school year.

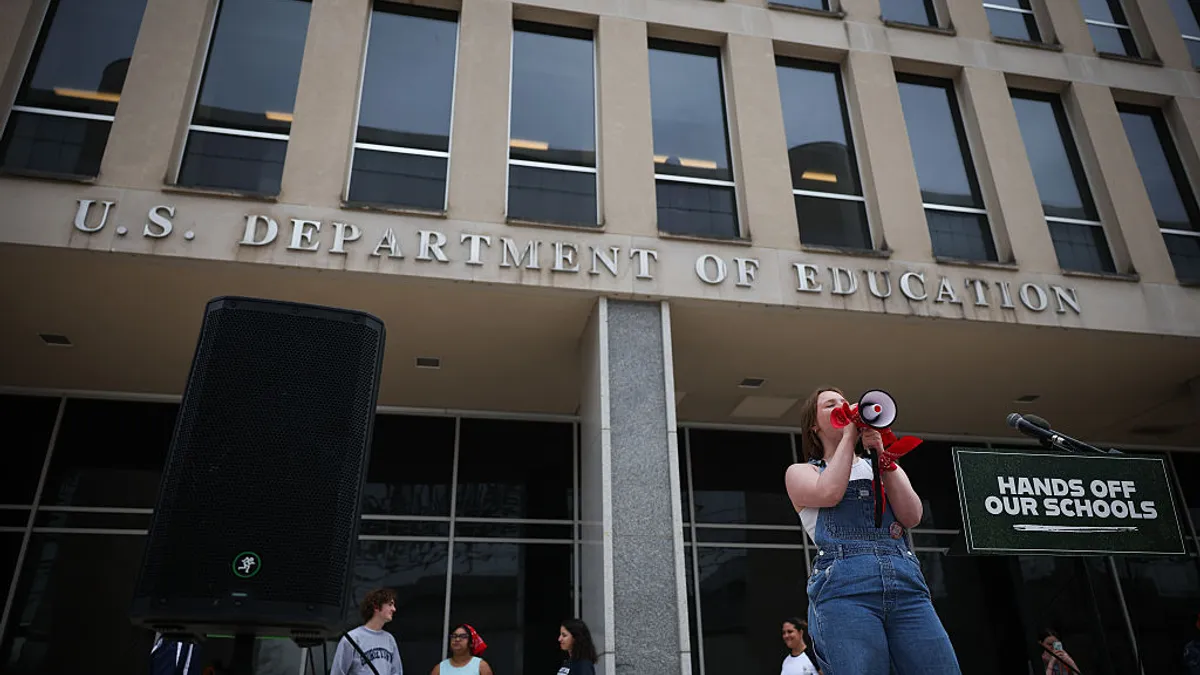

With those waivers set to expire June 30, school nutrition advocates had urged Congress for an extension in the federal fiscal 2022 spending bill.

But that didn’t happen, as an appropriations bill without the waivers passed the House Wednesday night and then the Senate Thursday night. The bill now awaits President Joe Biden's signature.

Not only will universal school meals come to a screeching halt this summer, but schools will also lose flexibilities and increased reimbursement rates that USDA provided through other waivers to help district nutrition programs cope with supply chain woes.

The cost for Congress to continue USDA’s waiver authority in this spending bill was estimated at $11 billion, Politico reported.

Still, the School Nutrition Association was surprised when the pandemic-era waivers lost momentum in Congress, said SNA spokesperson Diane Pratt-Heavner.

“The loss of child nutrition waivers will devastate school meal programs, impacting millions of students and working families who increasingly depend on our meals,” said SNA President Beth Wallace in a statement. “Congress’ failure to act will undoubtedly cause students to go hungry and leave school meal programs in financial peril.”

Wallace is also executive director of food and nutrition services of Jeffco Public Schools in Denver.

Providing universal meals is ‘a justice imperative’

When the waivers expire, those who are eligible for free and reduced-price meals will have to fill out applications to participate in the program again.

At the SXSW panel Monday, FoodCorps President Robert Harvey called the income test for free and reduced-price meals an outdated model. FoodCorps is a nonprofit that works with communities to connect children to healthy meals in school.

“It’s an income test that we don’t use for anything else in our public school system,” Harvey said. “There’s no income test for books. There’s no income test for recess. There’s no income test to access school nurses. There’s no income test for any other service provided by schools.”

Speakers on the panel highlighted how school meals provide a sense of belonging and said good nutrition is imperative for learning.

“Healthy school meals for all, at its core, is a justice imperative,” Harvey said. “It’s a real demand that every young person deserves the right to their bodies being well at the entry point to schools.”

More than free meals

While there’s a lot of focus on the universal school meal waiver, there should also be concern over the many other waivers that made it possible for school nutrition programs to operate during the pandemic, said Suzanne Morales, director of nutrition services at Placentia-Yorba Linda Unified School District in California.

“It was more than just all kids receiving food for free,” Morales said. “It was so much more and so much deeper than that, and basically, in one fell swoop everything was gone.”

School meals will be free for all students in California starting this fall, but Morales still doesn’t know how she’ll run her district’s summer meal program without the expiring waivers.

As food costs have risen and supplies have become more difficult to find on a daily basis, Morales is worried school cafeterias will need to rely on a district’s general fund to stay financially afloat. In most cases, school nutrition programs are financially independent of the district’s budget, but if they’re in the red they have to dig into it.

This means nutrition programs will be taking money away from other district priorities such as paying for more teachers or updating the curriculum, Morales said.

Building on the momentum of pandemic-era waivers

Morales is still hopeful Congress will pass individual bills to renew each waiver.

But if that doesn't happen and universal school meals are no more, there are other opportunities to leverage policies and ensure free meals for all students at the state level, as has been done in California and Maine, said SXSW panelist Luis Guardia, president of the Food Research and Action Center, an advocacy group looking to improve the nutrition, health and well-being of people struggling against poverty-related hunger.

For instance, Guardia said, Congress could expand the community eligibility provision. That provision allows districts in low-income areas to serve meals at no cost to all enrolled students without requiring individual families to apply for free and reduced-price meals.

Energizing local coalitions to advocate for universal meals is key, too, when considering how to make change happen at the state level, Harvey said.

“I think it’s important to note that caregivers and families often don’t recognize how much advocacy power they have to turn the lever around sustainable change in their local school district, but also at the state level,” Harvey said.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards