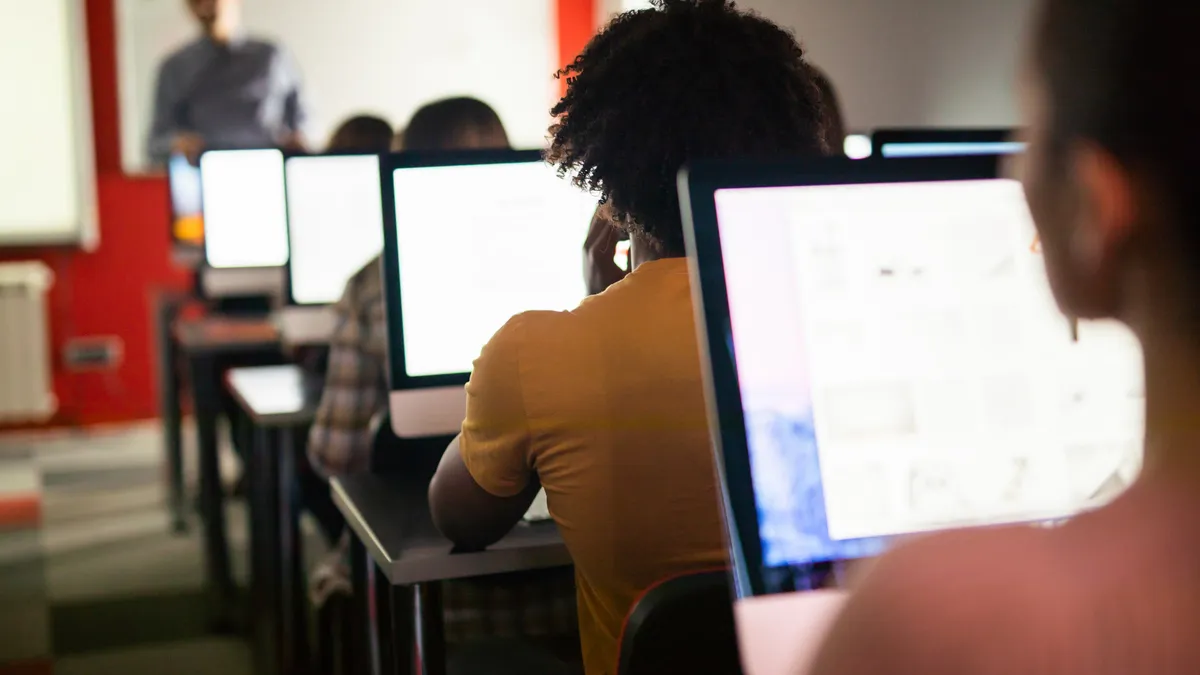

Students spread out around a room — some at tables, some on the floor. All are engaged in conversations with their peers about the text currently being learned.

They had a say in what they were learning and what the end product would like.

This could be assessment and was in my high school English classes in New York City. Students were regularly expected to participate in the development of the projects and eagerly contributed to how the learning looked and how it would be assessed against the standards. Although the adjustment to get to this place was a bit clunky, the end results were always better than what would have happened had I been asking them all to do the same thing.

So much of the way we assess in schools comes down to what happened to us as learners or what we perceive is expected of us from powers that be, whether they are our administrators or state regulators. We torture our students and ourselves to test learning to death, much to the detriment of all involved.

But learning can be assessed on a more regular basis in a more authentic way.

Creating learning experiences that center around projects that are backward-planned against standards offers students the opportunity to collaborate with peers and then apply their knowledge on independent work, where they can be assessed via rubric and self-reflection.

For example, in my high school English class, we read Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” when we were first learning about satire. Students worked together to get through the text, focusing on his writing and the elements of satire shown. After examining the proposal, students wrote their own “modest proposal” on a topic that mattered to them. They did research and then they had to synthesize the learning into a formal piece of writing. Given a schedule of benchmark dates, time in class, and individualized direct instruction based on the data collected during class time, each student learned how to write satire. At the end of the experience, they wrote a formal reflection/self-assessment that asked them to rate their learning based on the rubric we created.

Before reading the student’s work, I read his/her reflection. This set the tone and lens for my reading and potential preparation for providing appropriate feedback. Since students talked about goals set and areas of their writing they were working on, I knew how and where to focus my feedback for each individual student, stretching the learning beyond when they turned the paper in. Additionally, students were challenged to keep a record of the feedback and how they addressed it moving forward. This material would often be mentioned and/or referenced in their reflections, as well.

Since satire didn’t end with “A Modest Proposal,” students got to work in groups to explore "Gulliver’s Travels" and create a product that showed their understanding of the historical significance and/or the author’s craft. Some groups of students made interactive maps, while others created resumés for Gulliver. As I read each group’s interpretation, I had a good sense of their learning. Then they presented to their classmates, receiving feedback on their learning from their peers as well as from me. We often used Google forms to collect the feedback and then continued collaboration for the learning experiences that would follow.

Since all the learning was connected, it was easy for students to address both new skills and practiced skills in different kinds of learning, all of it that was creative and synthesis based. Students worked harder than they would have if I gave them a test on the subject area and were able to make their learning deeper with each new text we explored around the topic. The official end to the satire unit was a movie they created around a different text after we explored some non-traditional satires like South Park and Saturday Night Live. It’s not hard to believe that students enjoyed coming to their English class even though it was senior year and so much was expected of them.

As a school leader now, encouraging my team to take risks with their students and move away from traditional testing has been challenging. That isn’t to say it isn’t happening, but the culture is very different from the one I taught in. As each classroom takes on different kinds of formative assessment — like station-based activities that ask students to activate prior knowledge around a text by using historical documents, or creating project based units around the Civil War Battles that are shared in a museum-style gallery walk — no one can dispute the value of the learning that happens in this way. Students are engaged in the learning and feel ownership of their choices and the work. It’s truly a win-win for the teachers and the students.

The best part is that, when it comes time to review the final assessment, each is unique and shows different aspects of the learning. There's no more grading fatigue because we’ve been interacting with kids the whole time, and there is no cookie-cutter way to do it.

How do you engage students in the assessment process and how does their learning foster growth in future learning experiences?

Starr Sackstein is the Director of Humanities in the West Hempstead Union Free School District in New York. She was a high school English teacher in New York City schools for 16 years and has written several books on the topics of assessment, questioning, reflection and blogging. You can follow her on Twitter @MsSackstein.