This is the latest installment of Study Hall, an occasional series that serves as a one-stop shop for must-know information on critical topics impacting schools. For previous installments, click here.

Almost every school district in the U.S. participates in the 28-year-old E-rate program, which offers federal funds to help pay for affordable internet services.

But now the popular program's future is in doubt, as a federal appeals court has struck down the Federal Communications Commission's funding mechanism for the program and the Biden administration is seeking U.S. Supreme Court review of that decision. Here K-12 Dive breaks down the basics of E-rate and what’s ahead for the program.

What is the E-rate program?

Also known as the schools and libraries universal service support program, E-rate helps connect schools to affordable broadband.

The program is administered by the nonprofit private corporation Universal Service Administrative Co., or USAC, under authority of the FCC. USAC processes applications, confirms eligibility and reimburses service providers in addition to eligible schools and libraries for discounted internet services.

There are two channels for services that schools and libraries may request funding for under E-rate. Category one services cover telecommunications, telecommunications services and internet access. Category two services cover internet access in schools and libraries, including internal connections and basic maintenance.

How much does E-rate cost?

The annual funding cap for the E-rate program is $4.94 billion.

In fiscal year 2024, schools and libraries requested $3.2 billion in E-rate funding, according to Funds For Learning, a firm that consults with schools and libraries on the program.

Schools and libraries’ discounts for internet services are dependent upon their communities' poverty levels and if they are located in an urban or rural area, according to the FCC. Discounts through E-rate vary widely, from 20% to 90% of the costs for eligible services.

How long has E-rate existed?

The E-rate program was established when former President Bill Clinton signed the Telecommunications Act of 1996 on Feb. 8, 1996.

In 1995, only 8% of public school classrooms had internet access, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics. The law aimed to provide affordable access to telecommunications services for all eligible schools and libraries, especially in rural and economically disadvantaged communities. By 2003, 93% of public school classrooms had internet access, NCES data shows.

How has E-rate expanded?

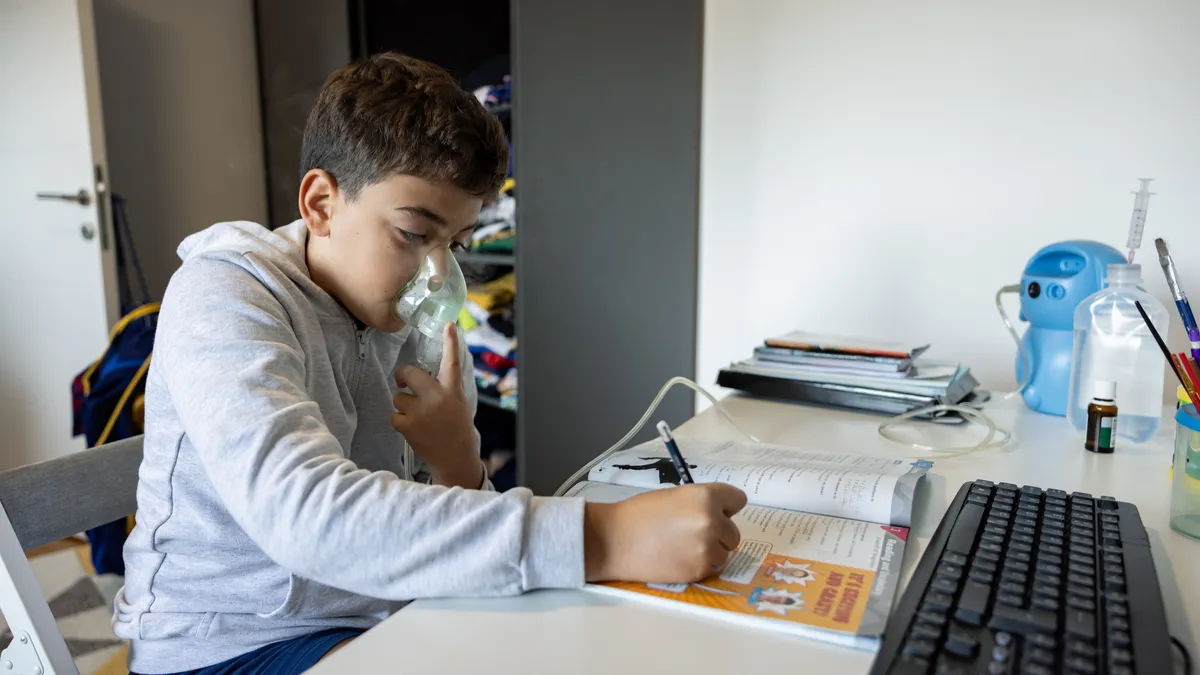

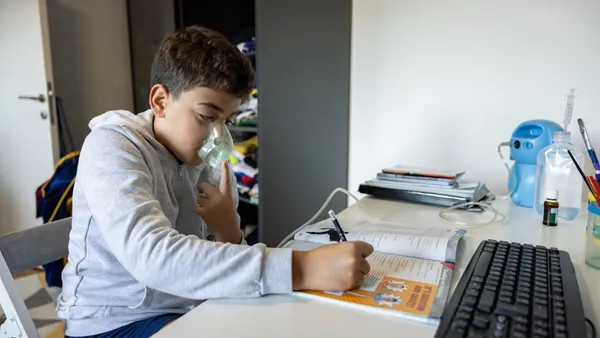

In July, the FCC voted 3-2 to expand the E-rate program to include the purchase of Wi-Fi hotspots by schools and libraries.

Commissioners in favor of the expansion cited the need to close the homework gap, which is when students who lack home internet access struggle to keep up with their peers on schoolwork. However, the two dissenting commissioners said the move exceeded the FCC’s authority over the E-rate program and could be an unsustainable use of taxpayer dollars.

Schools and libraries will be eligible to use E-rate funding for Wi-Fi hotspots beginning in fiscal year 2025, according to the FCC.

Also in a 3-2 vote, the FCC in October 2023 approved the expansion of E-rate to support the costs of Wi-Fi on school buses. Eligibility for those services began in fiscal 2024.

Why is E-rate’s future hazy?

E-rate’s future has been in limbo ever since the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in July struck down as unconstitutional the funding mechanism for the FCC’s Universal Service Fund, which operates the E-rate program.

For now, however, E-rate continues to be in effect — as the Biden administration challenges that ruling.

The U.S. Supreme Court is set to review the 5th Circuit’s decision, with oral arguments expected to be held in March or April 2025. The decision would likely be released by the end of the court’s term in late June or early July.

On Sept. 30, U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar asked the U.S. Supreme Court to review the 5th Circuit Court’s decision. In Prelogar’s writ of certiorari, she said the lower court’s ruling “threatens to nullify the universal service programs.”

“If the Fifth Circuit’s decision is allowed to take effect, carriers in that circuit (and perhaps elsewhere) are likely to argue that they no longer have a legal obligation to make universal service contributions because the FCC and the Administrator lack the power to collect such payments,” Prelogar wrote.

“Such a development would devastate the FCC’s ability to ensure sufficient funding for universal service subsidies going forward,” the solicitor general said.

The 5th Circuit's 9-7 decision in Consumers’ Research v. FCC said the commission’s delegation of taxing power to a private corporation, which then determines how much U.S. citizens have to pay to finance the Universal Service Fund, is a “misbegotten tax.”