The iPad used to hold an exciting spot in education administrators’ minds. One-to-one programs that paired all teachers and students with an iPad gained traction. One educational technology expert called them the “cool, sexy device” that everyone wanted.

But in the past year, it seems that tide has turned. Scandals and budgetary concerns have beset iPad rollouts, most famously in Los Angeles, and school administrators have begun to think more carefully about how exactly to implement ed tech initiatives and what technology works best for them.

When the Los Angeles Unified School District first announced its $1.3 billion deal with Apple to provide an iPad to every public school student, it seemed too good to be true. Very quickly, it became clear that it was. There were reports of students having the devices stolen on the street, technical glitches, and unlocked devices that let students freely roam the internet.

And then it took a turn for the scandalous. Now it looks like the bidding process for the contract may very well have been unfair, prompting an FBI probe.

Leslie Wilson, CEO of the One to One Institute and a former Michigan school administrator, said she knows of several districts that saw what happened in L.A. and decided to take a different path.

“I could name ten off the top of my head that watched that and said, ‘That’s not going to be us,’” said Wilson. Instead, those districts decided to take a more measured approach and look across the array of potential ed tech products before diving in.

“When they’re making these decisions about spending millions of dollars…they want the device that does what they need,” said Wilson.

In some cases, that means they've decided iPads, with their proprietary software and more image-driven interface, are not what they're looking for. Allison Powell, vice president for new learning models at the International Association for K-12 Online Learning, says it often depends on what grade level the devices are intended for.

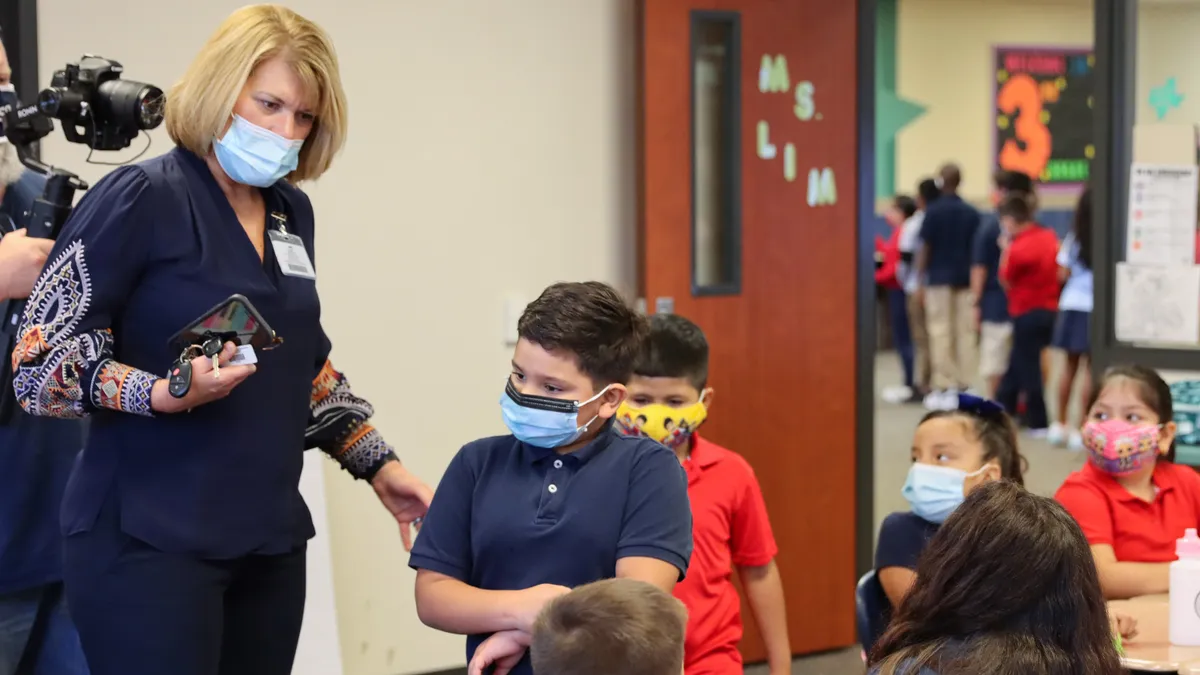

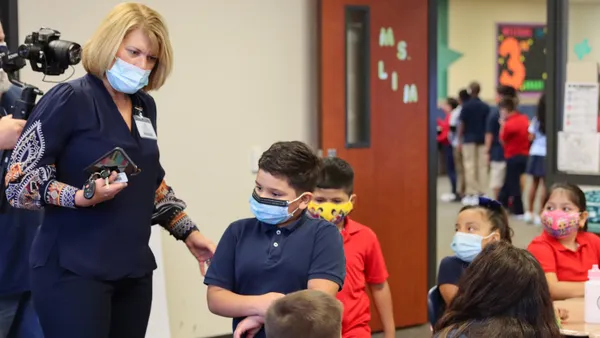

“Early grades do really well with the iPads,” Powell said. “Especially in kindergarten and in first grade, there are more images they can use.”

But if districts are looking for a device for older students, who will spend much of their time doing research and writing, Chromebooks and laptops are becoming the devices of choice.

Even if the iPad proves to be the right choice, district administrators can still face a hard road to getting and keeping them in the classroom. Fluctuating budgets, for example, can put an end even to a promising program. Take, for example, Minnesota's Rochester Public Schools, which recently touted the successes of its pilot one-to-one iPad program to its school board.

"The feedback that we got from teachers has been overwhelmingly positive,” Brandon Macrafic, an administrator at Rochester Public Schools, told KTTC. “I never expected to see some of the things that I've seen just visiting classrooms."

But the program, which was slated to roll out to all of the district's schools by the 2017-18 school year, may be on hold due to budget concerns.

Wilson says budgeting can be the biggest hurdle for schools to pin down, since they often don’t know what their future funding will be.

“It takes courage and tough decision making,” she said. “It takes a leader looking at the legacy spending they’ve had over years and years.”

Districts have also become more methodical about how they implement big shifts. Both Wilson and Powell have developed roadmaps for districts to follow that include setting concrete learning goals before launching any major programs and encourage making teacher buy-in and training an integral part of the process.

Some school administrators point to L.A.’s scandal as an example of a failure to do exactly that. Alberto M. Carvalho, the superintendent of Miami-Dade County Public Schools, told the Hechinger Report that LAUSD's failure to rethink the teaching skills and supports needed as part of the iPad rollout was their "Achilles heel."

“You put it in the hands of kids and teachers, but…the teachers were never trained on how to use it,” Carvalho said. “You need to have that training as a constant thing – not just a one-shot injection.”

As part of Miami-Dade’s plan for blended learning, teachers have shared planning time each day. Skipping that kind of common planning time, he says, “is a recipe for disaster.”

Would you like to see more education news like this in your inbox on a daily basis? Subscribe to our Education Dive email newsletter! You may also want to read Education Dive's look at 4 game-based testing approaches changing the face of assessments.