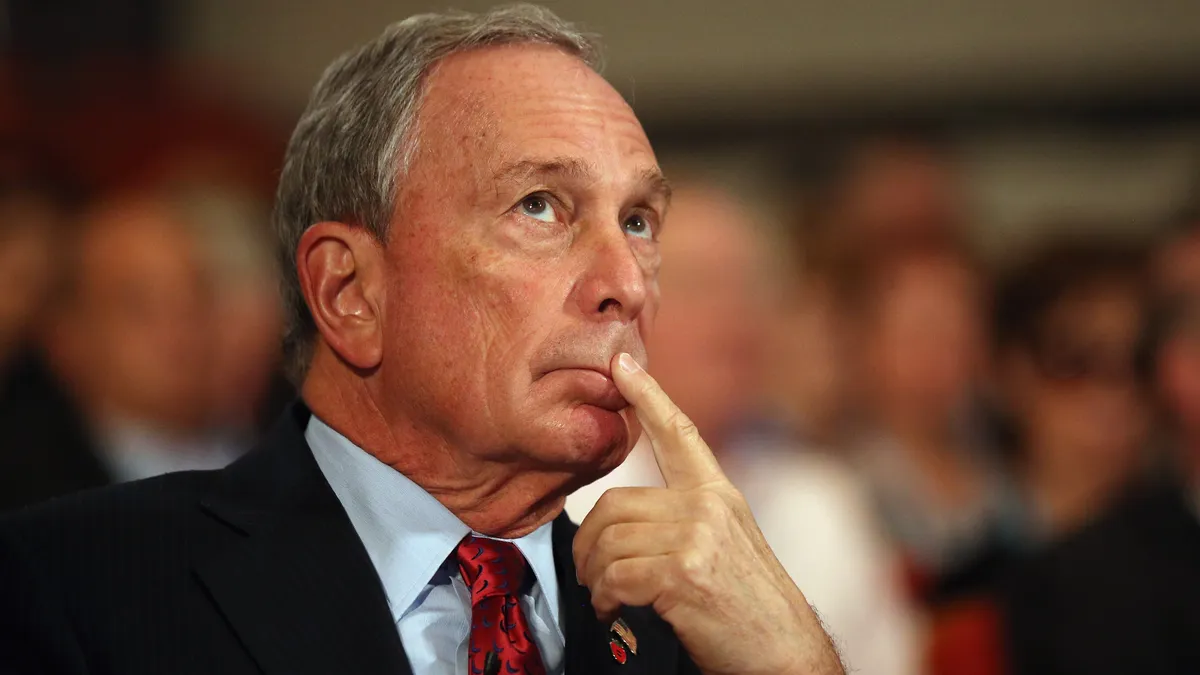

Earlier in December, billionaire and former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg announced he would donate $750 million to grow charter schools in 20 metropolitan areas nationwide.

Bloomberg’s donation will cover a five-year period and is significant compared to the $440 million allocated by Congress to charter schools in 2021. If that federal funding continued at the same rate for the next five years, it would total $2.2 billion. That means Bloomberg’s donation would be equal to a third of federal funding for charter schools over that period.

The $750 million donation could significantly help in the construction of new charter schools, said Debbie Veney, executive vice president for communications and marketing at the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. Since charter schools have to raise their own funding to build new schools, Veney said, this donation is notable for helping speed that fundraising process.

But some education reform experts don’t see how Bloomberg’s large donation will help shift the needle in public education.

Donation not a ‘scalable solution’

On average, students in traditional public schools perform just as well as those enrolled in charter schools, said Jennifer Steele, an urban education reform expert and associate professor at American University’s School of Education. However, in competitive charter schools with waitlists, students do tend to outperform their peers in traditional public schools, Steele said.

“For the individual, certain charter schools can be a lifeline and provide opportunities,” Steele said. “But nationally, charter schools are only about 7% of public schools, and they serve about 6.3% of public school kids. So this is less than 10% of the public school education sector.”

Because of charter schools’ small makeup in public education, Steele doesn’t think Bloomberg’s donation will be a scalable solution.

Noliwe Rooks is the department chair of Africana Studies at Brown University and coined the term “segrenomics,” referring to how certain educational reforms, including charter schools, vouchers and cyber schools, are marketed as solutions for equal opportunity but in fact ultimately worsen racial and economic segregation.

Like Steele, Rooks said charter schools don’t have a widespread benefit for the majority of students, adding that research on the performance results of charter schools “are mixed at best.”

In his Wall Street Journal opinion piece announcing his donation, Bloomberg declared the “American public education is broken” and said the traditional K-12 public school system is too hard to change.

Bloomberg pointed to the progress of Success Academy’s network of 47 public charter schools serving New York City children, most of whom live below the poverty line. The academy’s students are outperforming public school students in Scarsdale, New York, which is the wealthiest town on the East Coast and the second-wealthiest town in the U.S., he wrote.

Education must be rebuilt from the bottom up, Bloomberg said, otherwise the most vulnerable will be doomed to a life of poverty and even incarceration.

“There should be no connection between family income or skin color and a student’s opportunity to receive a great education—not in college, and not in elementary, middle or high school either,” Bloomberg said on the purpose of his charter school donation.

Competition for traditional K-12?

There are two arguments as to whether charter schools help create competition in K-12 that will bring improvements — and if that’s a good thing or not, Steele said.

School charter advocates say the competition will spur innovations that traditional public schools can adopt, she said. On the other hand, one could argue families with the most resources and access to information will choose charter schools over traditional schools, and consequently, the strongest public school community voices will be diverted from traditional K-12 schools, Steele said.

Rooks said she finds the public school competition argument flawed to begin with. There’s a narrative that charter school interventions that take funding away from traditional public schools will improve traditional K-12 schools through competition, she said.

“There is just zero evidence that that’s the case. Like literally, almost zero,” said Rooks.

Because public school funding depends on enrollment, traditional K-12 schools financially suffer when their students leave for charter schools, Rooks said.

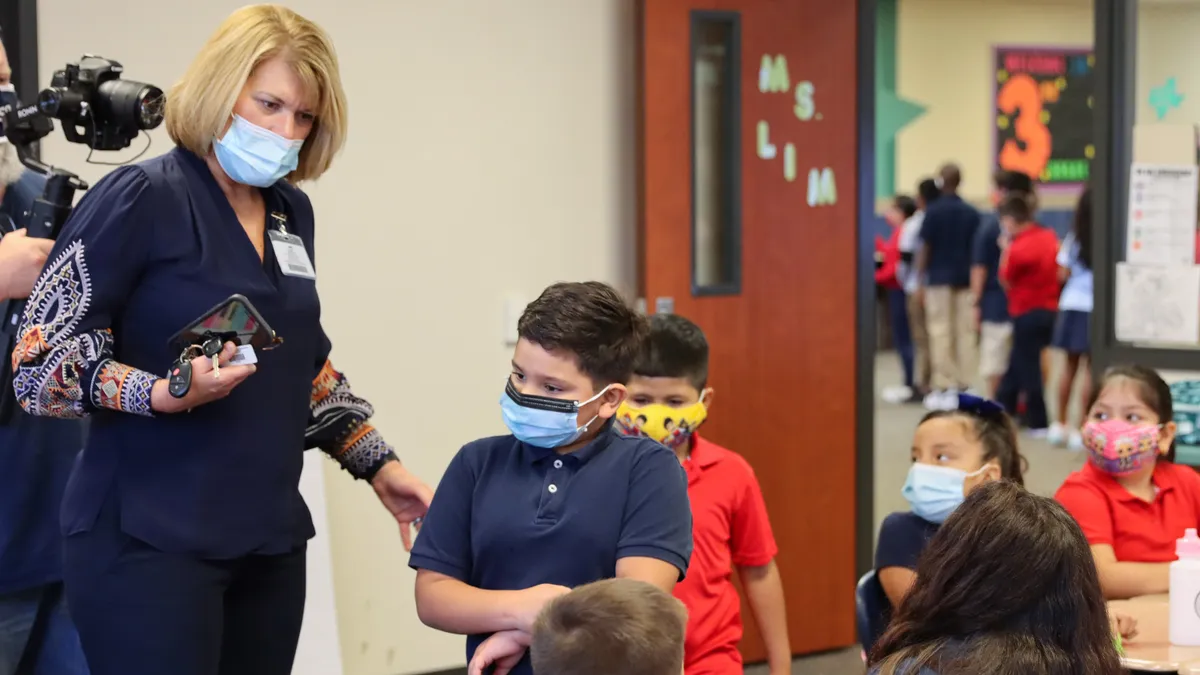

In fact, recent reports reveal pandemic-related enrollment declines in traditional K-12 public schools nationwide continued with a 3% enrollment drop in the 2019-20 school year. Meanwhile, charter school enrollment grew by 7% during the 2020-21 school year, the greatest increase in five years, according to the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools.

Educators and researchers believe many of the students leaving traditional public schools during the pandemic are now being homeschooled or moved to private or charter schools.

Veney, a charter school advocate, emphasizes charter schools are still public schools. She said it’s important to put money into models that work, including charter schools. But it’s not productive “to throw stones” at other public schools, Veney said.

About 69% of all charter schools students are of color, Veney added. Charter schools aim to serve underrepresented communities, and they also typically provide more instructional days than traditional K-12 public schools do, she said.

Students in urban charter schools gain on average an additional 40 days of math and 28 days of reading instruction, Veney said. This is possible because charter schools have more flexibility to rethink the length of school days and the amount of instructional time for subjects, she said.

Bloomberg also noted that charters have more flexibility to navigate staffing, curriculum, testing and compensation without operating under union contracts.

“This allows them to create a culture of accountability for student progress week to week that many traditional public schools are missing,” Bloomberg wrote.

A call for K-12 community engagement

If traditional public schools want to keep students from moving to charter schools, Steele said, these schools will have to be more attentive to the needs of the whole child and to engage families more.

“Every single parent cares about their child’s education, so there has to be a partnership between parents and schools. Be that charter schools or traditional public schools,” Steele said. “That partnership, that openness has to be there and it’s been compromised by COVID, because literally, people are kept out of the building for safety reasons.”

Overall, the relationships between schools and families have to be rebuilt by addressing the individual needs of students, she said. Steele recognizes that’s a difficult task to take on at a large scale for traditional K-12 schools, but she said teachers are able to rise to this challenge with the support of administrators.

Rooks is also beginning a project at the newly founded Segrenomics Lab at Brown University to explore bottom-up policymaking. This entails asking parents, teachers and students about their ideas for addressing education issues, including the teacher shortage.

The project seeks to understand what people most impacted by education reform actually want to see enacted, rather than relying on lobbyists to shape education policy.

“I just don’t think we’ve tried very much,” Rooks said. “In the history of American public education, trying to educate poor kids, Black kids and Latinx kids … we just haven’t tried that much. We keep doing the same thing and calling it a new intervention, and I think that it’s time for some actual new interventions.”

Dive Awards

Dive Awards