Suicide rates among children and teens were already on the rise before the pandemic. When COVID-19 surged, it added new stressors as young people endured isolation, which, in some cases, was accompanied by family upheaval and trauma. While students experiencing preexisting physical or mental health issues are particularly vulnerable, the risk of suicide must be front of mind for anyone who regularly works with youth. Schools, in particular, can play a vital role. One study found that school-based services can significantly decrease suicidal behavior and substance abuse among those at risk.

Is your school or district prepared to identify students in need of additional mental health support and connect them with the care they need? Here is what every K-12 educator should know about youth suicide and how to best protect students.

Suicide risk grows as stressors rise

The incidence of youth suicide has been growing for some time. Between 2007 and 2018, suicide rates among people aged 10 to 24 in the U.S. increased by 57% to 10.7 per 100,000 individuals. The problem has continued unabated. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), suicide was the second-leading cause of death in 2020 among individuals between the ages of 10 and 14 and the third-leading cause of death for those ages 15 to 24.

Selina Oliver, a Nationally Certified School Psychologist and senior assessment consultant at Pearson, cites three potential factors in this distressing surge.

The first factor is social media. She attributes its damage to the feelings of worthlessness it can instill in kids who judge themselves based on how people react to their social media presence or how peer posts might contribute to feelings of missing out.

“When we’re thinking about suicide, it affects people who have feelings of worthlessness and helplessness, and, unfortunately, social media does a great job emphasizing this pain,” Oliver says. Additional aspects include the risk of increased cyberbullying and a recent rise in publicizing social media influencers who have died by suicide.

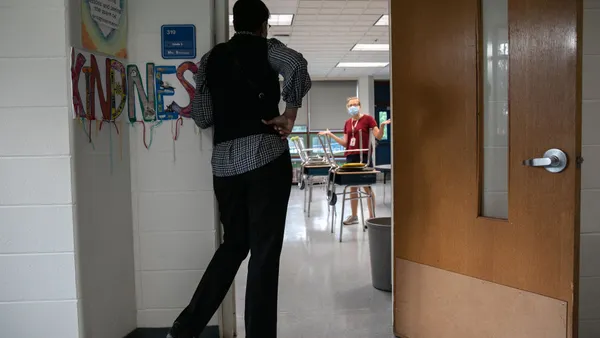

The second factor is the ongoing school staff shortages, the impact of which is felt in several ways. Not only are schools severely limited in the number of qualified mental health professionals per student, but there's also a shortage of other staff members who typically would play an informal “surveillance role” with kids. These include bus drivers, cafeteria assistants, custodians and administrative staff. “Those folks have a high degree of interaction with the kids. For some students, the only person who says ‘Hi’ to them all day might be the cafeteria worker or the bus driver,” Oliver notes.

A third factor may be the change in school health room access rules, arising from new policies designed to prevent the spread of COVID-19. “Health rooms have typically served as an oasis for kids who are anxious or who have experienced other mental health concerns yet are not able or willing to go to the school-based mental health professional,” Oliver explains. “They were a safe haven, where the staff played a vital monitoring role in picking up on changes in kids as well as providing some sense of hope.”

Meeting youth in their moment of need

While many risk factors for suicide are well-known (and can be reviewed on the CDC website), Oliver shares one that is less obvious and easily overlooked: a change in behavior, which often manifests as an improvement.

“Many youngsters and adults who are troubled and have displayed disturbing behavior sometimes exhibit calmness and more self-control once they’ve made the decision to die by suicide,” she says. “It’s as though they are feeling relief in anticipation.”

Oliver also advises educators to be attuned to kids who might slip under the radar. “While they’re not problematic or making trouble, and might not appear to be isolated or bullied, they could be at risk,” she says.

Powerful ways to make a difference

There are many ways educators can help address suicide risk factors with their students, Oliver says. For example, unseen isolation can be identified and managed by using a tool like a sociogram at the beginning of the school year to track how kids are interacting with each other. “The teacher can analyze the data to see if maybe there’s one child whom no one opts to sit near or partner with.”

Educators should be aware of the CDC’s “protective factors” against the risk of suicide, which include problem-solving and coping skills, along with feelings of connection to others. Lesson plans can include activities that help build these skills to address feelings of worthlessness, hopelessness and helplessness that frequently bolster suicidal thoughts. Try adding a compliment jar to the classroom or ensuring every child has an opportunity to demonstrate their strengths, Oliver suggests.

She also urges teachers to display solid classroom management. “That can eliminate a source of anxiety for kids because a chaotic classroom can be very provoking,” she says. “Teachers should make a point to engage students each day by greeting them as they enter the classroom. For kids who are feeling isolated and invisible, just knowing there’s one person proactively looking for them every day can really help.” Good classroom management also entails zero tolerance for bullying and name calling.

In addition, Oliver recommends maintaining an open communication stream with parents and caregivers. “Many educators can be anxious about this topic, so they avoid it or pass it on to someone else, but they can really make a difference by having the courage to communicate with parents, who are most likely the ones who will eventually help students with their mental health needs.”

Embracing screening to spot issues early on

One of the best ways to help promote better mental health schoolwide is through universal screening, Oliver says. “It can be done quickly and creates a fair process in terms of diversity to assess if someone is at risk.” An easy-to-use universal digital tool can help educators set the stage, and direct evaluations can follow to help identify key concerns.

As K-12 schools grapple with the safety of their students, mental health assessments are an increasingly crucial component of a well-rounded support system. Learn more about how Pearson Assessments can help your school or district prioritize student mental health year-round.