This is the fifth installment of a five-part series on ransomware in schools.

With the influx of digital platforms and resources into schools over the last two decades, the K-12 sector has quickly become one of the most popular targets for hackers.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic forced a heavy transition to digital learning, the rate of adoption and the increasingly technological nature of classrooms was outpacing the ability of school district budgets to keep up with cybersecurity personnel and procurement needs.

Des Moines Public Schools is reaching out to nearly 6,700 individuals this week to notify them of a data security incident that occurred earlier this year. https://t.co/UvZIHiWTRI

— DM Public Schools (@DMschools) June 19, 2023

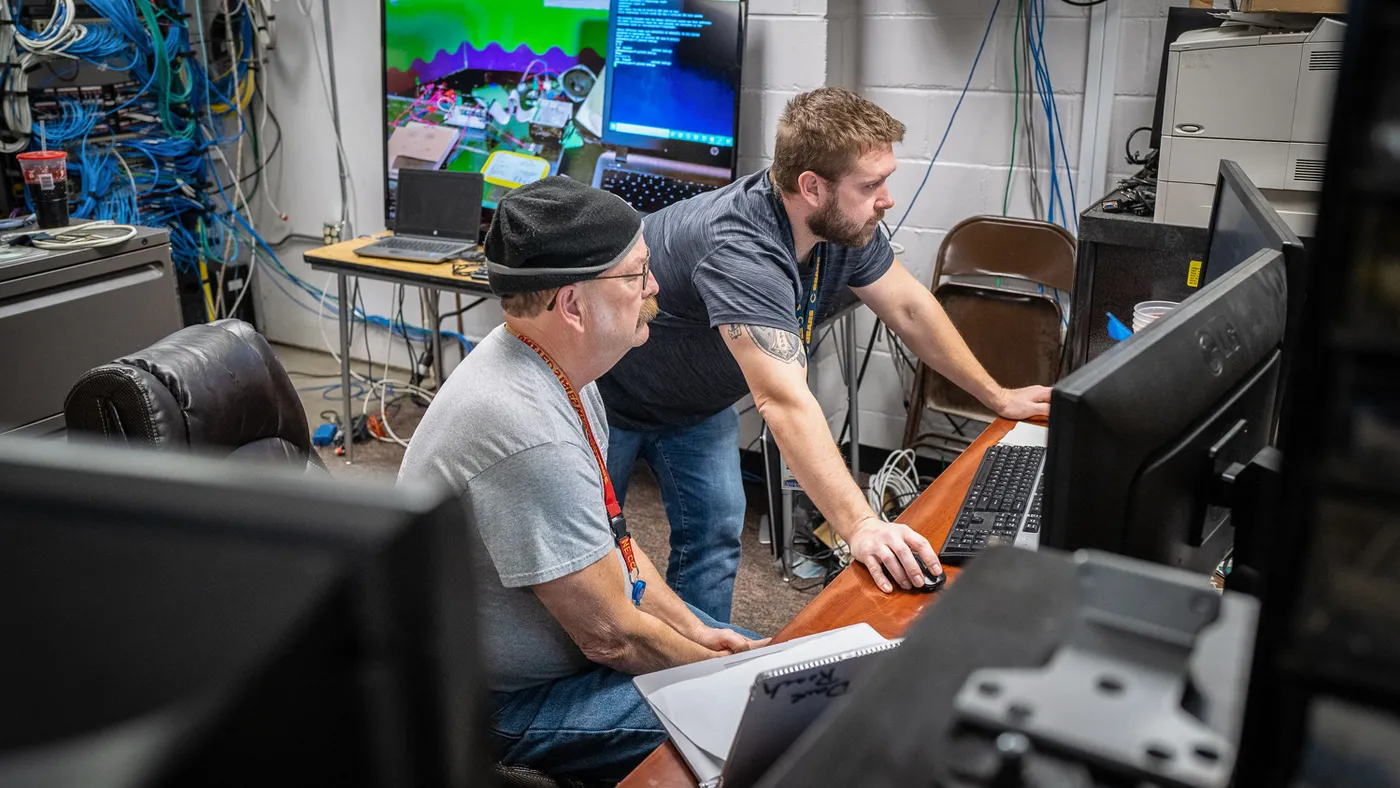

“This is now a 24/7/365 ask, with many districts not having the human or funding capital,” said Todd Wesley, chief technology officer for Lakota Local School District in Ohio.

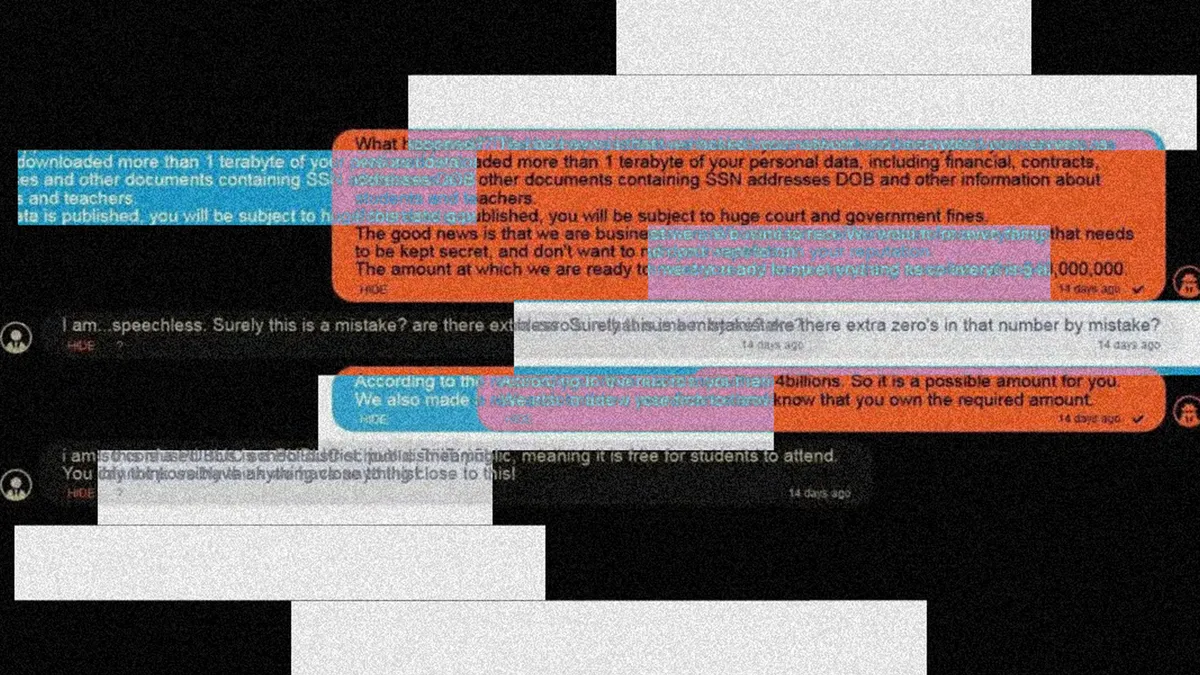

Ransomware is a particularly popular mode of attack for cybercriminals targeting K-12 schools, as it presents an opportunity for double extortion.

On the surface, school districts are caught in an impossible situation where essential, largely private data necessary for operations is encrypted and locked by an attacker who issues a ransom demand so districts can have their access restored. And even if schools pay the ransom — which the FBI advises against — there’s no guarantee that access or the data itself will be restored.

And that leads to the other head of the double extortion monster: Student data and identities are among the most valuable on the dark web, due largely to factors like the lack of credit history among minors. So a highly successful ransomware attack can net a payout from both the ransom itself and the sale of the stolen data on the black market.

While that’s bad enough news on its own, the hard truth of cybersecurity is that there’s no 100% guaranteed defense against attacks.

“We need more defenses, because the threat actors are becoming more sophisticated every day, and the defenses that we had are no longer sufficient,” said Lisa Irey, director of technology for Des Moines Public Schools in Iowa. In January 2023, DMPS fell victim to a ransomware attack that exposed the data of around 6,700 people.

“The strategy is we try to layer defenses to stop as many vulnerabilities as possible. You're never going to be able to plug every hole and stop every threat from coming in,” said Irey.

So what are beleaguered school districts to do? Here are four prevention and response recommendations.

Implement phishing tests

The weakest link in an organization’s cybersecurity is often the end user. It only takes one person clicking on the wrong link in a suspicious email to open the door for cybercriminals. Thus, it’s essential to train teachers, staff and students on what to look out for and why they must always remain vigilant.

One way many districts do this is through phishing tests, in which fake but realistic looking phishing emails are sent to users on the school system's network.

“I would even prioritize the individuals that you do that to,” said Adam Phyall, director of professional learning and leadership at the Alliance for Excellent Education, or All4Ed, a nonprofit that advocates for equitable educational opportunities for students of color, students from low-income families, and other marginalized groups.

The strategy is we try to layer defenses to stop as many vulnerabilities as possible. You're never going to be able to plug every hole and stop every threat from coming in.

Lisa Irey

Director of technology, Des Moines Public Schools in Iowa

For example, where all staff may receive a phishing test a couple of times a year, high-profile targets would be tested at an even greater frequency. This might include those working in human resources, business, the superintendency and other administrative roles with access to sensitive data.

“I would do my internal phishing more on them than others, because they hold more keys to the castle than other people,” said Phyall, also a former director of technology and media services for Newton County School System in Georgia.

For added protection, Irey also recommends that staff with access to privileged databases retrieve that information from separate accounts specifically set up for accessing that data — rather than retrieving all information from their standard employee account.

“Say an IT administrator has their regular employee account. There should be a separate set of credentials that they use to do their domain administration work or their service administration work,” Irey said. A domain account is used across multiple systems in a network, whereas a service account is created specific to a single system within that domain.

Both Phyall and Irey advise requiring all staff to use multifactor authentication at the very least.

“Personally, it's annoying at times to have to go to that authenticator app to confirm it, but it is that extra step in security,” Phyall said. “This is like putting that deadbolt on your door of your house. You’ve got it locked, but this is adding that deadbolt to it, giving you that extra layer of security in your network.”

Establish a backup network

One of the most prominent safeguards against ransomware is the use of backup networks, in which critical data and information is copied from all devices and storage spaces on a network to a backup server. That backup server in many cases may be located in the cloud rather than being a physical, on-premises server.

There are, however, risks to remain aware of with this approach.

For instance, Phyall said, districts need to vet the third party managing the backup server and also ensure that the backup is clean and doesn’t contain dormant ransomware or other malware waiting to be activated.

A third-party system conducting a backup can catch ransomware in a system — which is in some cases how districts have actually found out that ransomware has been embedded, Phyall said.

While backup networks have become a core component of protecting against ransomware in the business world, it’s often still not cost-effective for school districts to do the same.

For instance, a fully managed disaster recovery solution may have a base cost of $500 plus $2-3 per gigabyte per month, according to Optimal Networks, an IT services provider that works with law firms, associations and consultancies. If a district has terabytes — thousands of gigabytes — of data to back up, those costs can quickly balloon exponentially.

“We are tasked with trying to prepare our students for the future, but also protecting them and their information. And it's a fine line to try to balance” the financial limitations and the need to protect that data, said Irey.

Explore state and federal supports

Fortunately for K-12 tech professionals, a variety of supports exist at the state and federal levels.

“First and foremost, talk to your state education department,” said Phyall, adding that most states have some level of cybersecurity support in place for school districts.

Among state resources that Phyall named are specialized cybersecurity advisors, no-cost or low-cost cybersecurity audits, and additional network monitoring capabilities.

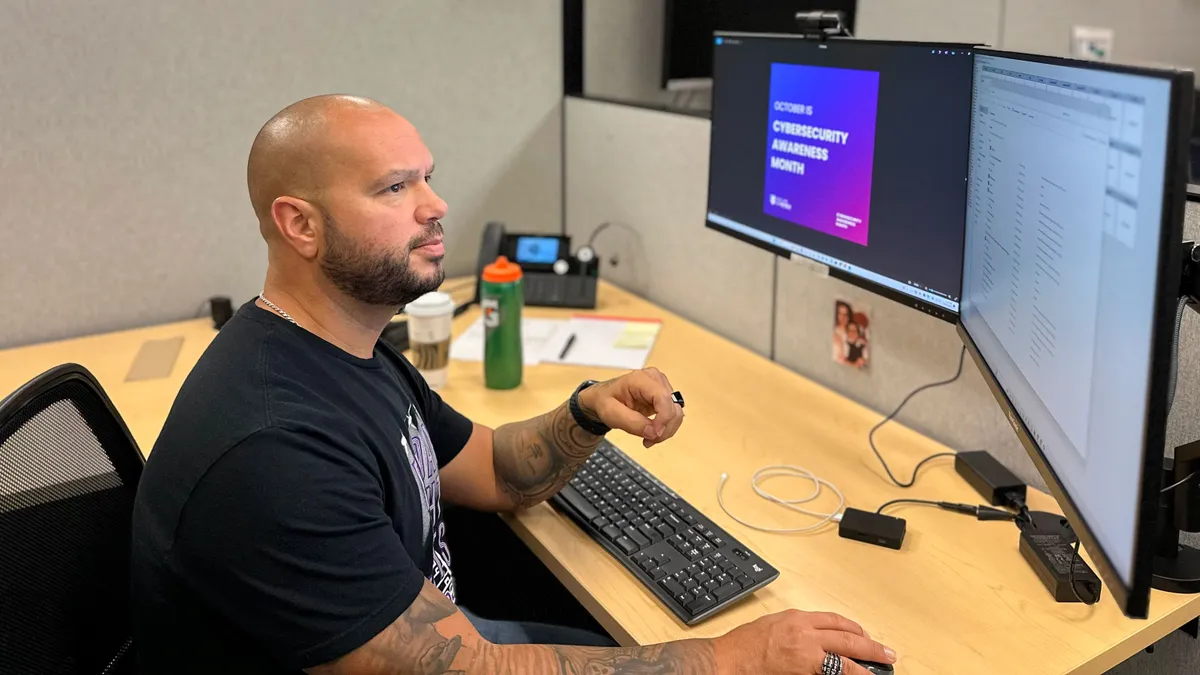

The Federal Communications Commission’s E-rate program, which helps schools and libraries access affordable telecommunications services, hasn’t typically covered cybersecurity tools and services. The agency opened the application window for its $200 million Schools and Libraries Cybersecurity Pilot Program on Sept. 17, and it will close end-of-day Nov. 1.

“That's definitely a step in the right direction,” said Irey. “I do hope that a lot of my peers will join me in applying for those funds so that we can show that this is a great need.”

Another resource, Wesley said, is the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency’s State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program, which offers funds to state and local government agencies. The program offered $279.9 million in grant funding in fiscal 2024.

Ensure that you have a plan in place for when it happens, not if it happens.

Adam Phyall

Director of professional learning and leadership at All4Ed

“This may allow state education departments to centralize services and support for K-12 schools at a cheaper cost and learn what is working and not working between states and districts more quickly,” Wesley said.

Phyall also recommends building relationships with local and federal FBI and CISA contacts.

“Ensure that you have a plan in place for when it happens, not if it happens,” said Phyall. “I think about it the same as in your own home, where you have the list on the refrigerator with your poison control" and other emergency numbers. "Have that list ready and available, so people know who to call when it happens.”

Remember to think about people first

Should the unthinkable happen and your district fall victim to a ransomware attack, it’s critical not to forget the impact on the information technology pros laboring to get things up and running again, said Irey.

For those who experienced the January 2023 ransomware attack against Des Moines Public Schools — "the people on my team — it was a grief event,” said Irey. “It was like losing a loved member of our family, if you think about all the time and energy that the people on my team took to build and care for a network that supports the work of 30,000 students, 5,000 staff.”

School districts rely heavily on these systems not just for business and academic operations, but to be able to remotely lock down schools in an emergency or to inform staff of students’ allergies, dietary restrictions and emergency contacts. A ransomware attack can significantly upend a school community for at least several days.

Among the things that stung the most for Irey’s team was knowing that the resulting two days of school closures interrupted access to essential services like meals for the 75% of students in the district who qualify for free and reduced-price lunch.

“Their safest place where they're going to have a lot of their basic needs met is at school,” said Irey. “So for our ransomware attack, for us to have to cancel school because we couldn't have the systems running that were going to keep us safe and keep us healthy, it actually was disadvantaging our students" who were already a vulnerable population.

Even after schools reopened, Irey said, it took the IT team several months to rebuild all of those vital systems. During that time, district leaders prioritized thinking about the people behind that work.

“The No.1 question I get is, ‘How many team members did you lose?’ Not a one, because we invested in our people and in our culture to where we had people dedicated to say, ‘You know what? This happened, we're gonna dig in and roll up our sleeves, and we're gonna work together to fix it,’” said Irey. “The culture of our school district was such that the finger didn't get pointed at us.”

In fact, students and teachers made the IT team thank you cards and sent them treats and care packages. "They knew what we were going through, and they were encouraging us,” said Irey. “We got a lot of grace to go through that.”

News Graphics Developer Julia Himmel contributed data and graphics support to this story.