This is the second installment of a five-part series on ransomware in schools.

At the start of the school day on Jan. 12, 2022, teachers in New Mexico's Albuquerque Public Schools tried logging into the district's student information system — but couldn't. When teachers flagged the problem to the district's technology team, IT staff members couldn't get access either.

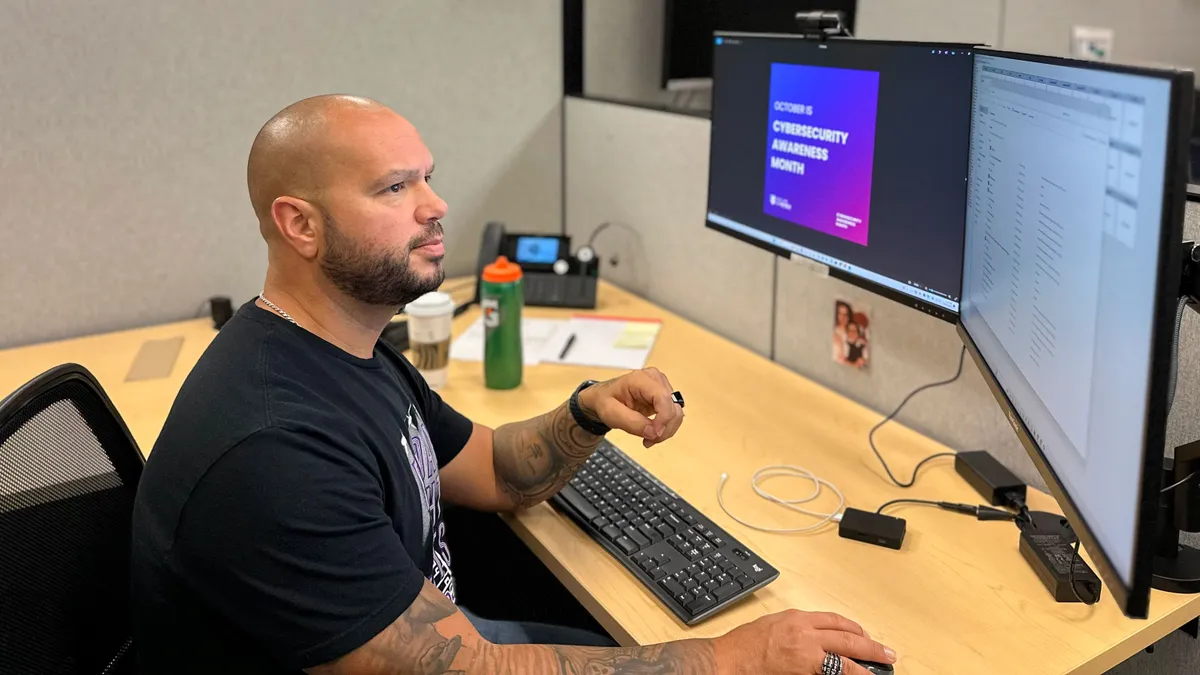

It was then that the technology team knew it had a big problem, said Richard Bowman, now the district's chief technology officer.

The access issues were determined to be a ransomware attack that forced the district to close school for two days, the district said in a February 2022 statement.

The school district has not disclosed if it paid a ransom, and Bowman would not comment on this.

However, according to a February 2024 article in School Administrator, the magazine of AASA, The School Superintendents Association, Albuquerque Public Schools didn't have to consider whether to pay a ransom because its data had not been compromised. In fact, a follow-up investigation had found no evidence that student or staff personal information was stolen during the attack, according to a March 2022 statement by the district.

But the incident required the school system to delicately manage communications within and outside of the district, quickly expend energy and resources to restore its compromised network systems, and coordinate with multiple partners as it built defenses to prevent future attacks.

Bowman, who was the district's chief information and strategy officer at the time, calls the attack "the most serious, the most devastating thing you could imagine for a system administrator of a critical system."

Even 2 1/2 years later, Bowman said talking about the attack can be emotional.

"When an incident like this happens, it's like your privacy is violated," said Bowman. "It's an attack on Americans, on the children of American citizens."

For security reasons, Bowman said he could not speak about certain factors of the attack. However, he did share aspects of the "complicated and sensitive" event, because he says he's a "teacher at heart" and wants others to learn from Albuquerque Public Schools' experience.

The attack

Even though the cyberattack was discovered as the school day dawned for the district's 70,400 students and 10,890 employees, Albuquerque Public Schools was able to maintain classes that day since email and online documents for administrative and classroom collaboration hadn't been affected.

But its student information system had been compromised. So teachers and administrators in the district’s 143 schools had to use pre-computer tactics like taking attendance on paper and making phone calls to contact families in emergencies or ensure students were picked up from school by authorized adults.

Meanwhile, in the technology office, staff were assiduously checking the district's online systems to determine where critical outages had hit. "The first step was to see how far does this spread?" Bowman said.

Technology staff removed systems from the network and tested each one to determine if it was safe to reconnect.

As the technology staff triaged the system, the district referenced the Federal Emergency Management Agency's Incident Command System. That resource provides guidance for handling crises, including how to create a chain of command for communications, operations and logistics.

Early in the incident, the district messaged its school community through social media and a letter and video from the superintendent with the information it could impart at that point — basically that it knew systems were down and officials were working to resolve the issue.

"In a fast-moving incident, it is difficult to clearly and precisely state exactly what has happened in any given point, because it just keeps moving, and the cost and consequence of speaking incorrectly or communicating inaccurately are very high as far as the loss of trust of the community," said Bowman, an eight-year veteran of the district.

Albuquerque Public Schools had alerted the FBI and other partners about the cyberattack. It also called its cyber insurance company, which put the district in touch with a legal team. Those attorneys connected the district with a digital forensics and incident response team to assist in investigating the attack and fixing district systems.

The school district set up a hotline for anyone in the school community to report suspicious messages. It then shared any tips received with law enforcement, Bowman said. He declined to say how many reports came in.

By mid-day, a decision was made to cancel school the following day, Jan. 13.

The response

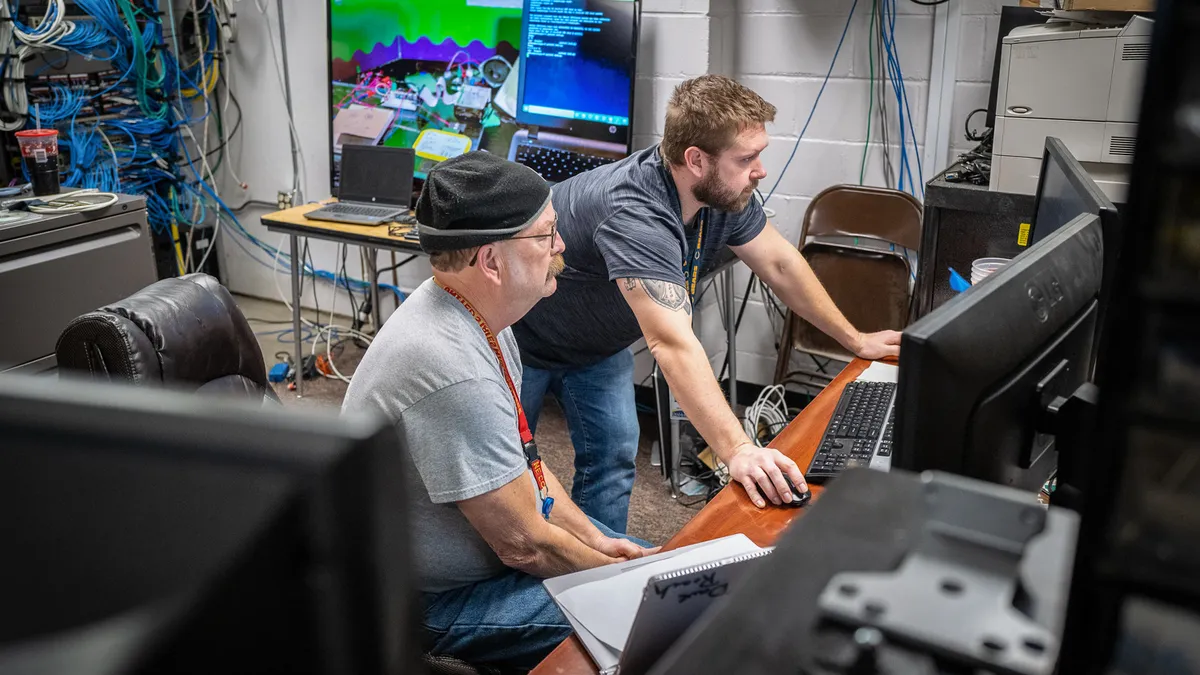

Over the next few days, APS technology staff worked day and night, eating meals in the office and consulting with both in-person and remote partners about the crisis.

After determining that the compromised system could be safely restored using the district's backup system, the staff got to work on carefully reconfiguring systems and confirming they were operating as expected. By mid-day Jan. 13, the decision was made to close school again the next day, Friday, Jan. 14.

Over the next few days, through Monday, Jan. 17 — which coincided with the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday when schools were already closed — the district and its partners "very steadily, very carefully" confirmed which systems were operational and which had to be restored, Bowman said.

By midday on MLK Day, officials determined that schools could open the next day. Students would have to make up the two "cybersecurity snow days" at the end of the school year, the district's February 2022 statement said.

But even when schools reopened on Jan. 18, the technology staff continued working behind the scenes to ensure all systems were operational, Bowman said.

In a fast-moving incident, it is difficult to clearly and precisely state exactly what has happened in any given point, because it just keeps moving, and the cost and consequence of speaking incorrectly or communicating inaccurately are very high as far as the loss of trust of the community.

Richard Bowman

Chief technology officer for Albuquerque Public Schools

The district, in an email to K-12 Dive, said it spent around $200,000 on emergency procurement due to the cyberattack, not including overtime, lost productivity and incidental costs.

When that work ended, the school system prioritized preventing future cyberattacks. It put out a request for proposals to companies that manage and respond to cyberattacks, eventually choosing England-based cybersecurity company Sophos for the contract.

According to January and February 2024 Sophos survey results of 300 education IT leaders from across the world, 63% of lower education organizations were hit with ransomware in the last year. That's down from 80% the year before, according to the polling.

That 63% ransomware rate placed the education sector as the third-most likely industry to suffer from ransomware, behind central and federal government (68%) and healthcare and energy, and oil, gas and utilities (both 67%), according to Sophos.

The company also found that 22% of ransomware attacks in K-12 school systems where data was encrypted resulted in data theft in 2024. That's down from 27% in 2023.

Albuquerque Public Schools pays $925,000 a year for Sophos anti-virus software and monitoring for the district's PCs and Macs. If a compromise does occur, the software can virtually shut down an affected computer's operation to stop a cyberattack from spreading to other devices, Bowman explained.

The district also worked with the federal Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency to use its free Cyber Hygiene Services that scan and test local governments’ vulnerabilities within their external networks or public web applications.

Even with all this protection, the district — like other school systems — is still experiencing cyberattacks regularly. But its defenses have prevented any widespread operational impacts, Bowman said.

New approaches

Bowman is one of many district administrators around the country calling for more financial support for schools' cyber defenses. "Cost is always an issue," he said. "There's always competing budget priorities."

A new initiative in New Mexico, called the Statewide Education Network, aims to connect public schools through a broadband network to boost student learning and cybersecurity.

The network, which is being implemented in phases, allows students to share resources and information and to access educational websites. It also aims to reduce cybersecurity risks through monitoring and tools to minimize the impact of distributed denial of service attacks — a type of cybercrime that overwhelms a server, network or site with malicious traffic to keep users offline.

The initiative has $500,000 in backing from the Federal Communications Commission's E-rate program. Albuquerque is one of the first school districts in the state to participate, according to an August announcement from New Mexico's Office of Broadband Access and Expansion.

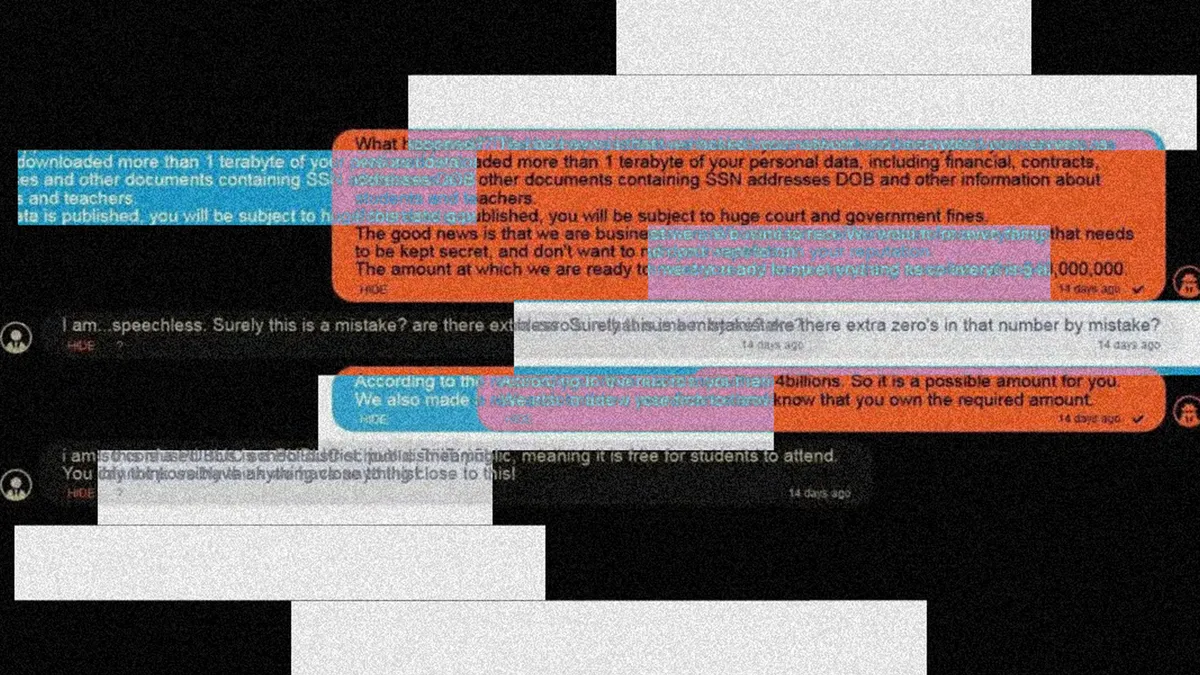

And while some are hopeful that generative artificial intelligence could be used to shore up cyber defenses, threat actors can also use the technology to improve their attacks by, for instance, communicating their demands with perfect English and grammar, Bowman said. Identifying grammatical and linguistic errors, as well as misspellings, is one way people can spot potential phishing attacks.

Bowman also would like to see more forums and professional development where school leaders and staff can learn about information security, especially about how best to defend K-12 from emerging cyber threats.

"The plethora of ways that bad actors have figured out how to sidestep the various types of security that you're putting in place, that is what keeps changing," Bowman said.

News Graphics Developer Julia Himmel contributed data and graphics support to this story.